Spotlight on Whitney Shefte

Jan 23, 2013

TID:

We're going to take a break from the usual deconstruction of a picture and instead focus on a video. Thanks for taking the time to share this with us on a very timely topic. Can you tell us a little of the backstory?

WHITNEY:

In 2007 I moved to Petworth, which is a neighborhood in northwest Washington, D.C., that is, at least since integration in the 1950s, a historically black, working class part of town. It's an area that has undergone its fair share of development and gentrification over the past several years, but still a space that plenty of native Washingtonians call home. One of the first things I noticed after unpacking the U-Haul was a teddy bear that had been nailed to a pole half a block away from my apartment. It was a handmade memorial for one of Washington's latest victims of gun violence. I knew about the shootings in D.C., but I had no idea they could happen so close to a place I was about to call home. Soon after that, I started to notice a disproportionate number of young, black males riding around the area in motorized wheelchairs. I figured it was unlikely that disease had put most of them in those chairs. I thought about the teddy bear and how some people who are shot surely survive. It didn't seem far fetched to guess that many of these men I had noticed were wheelchair-bound as result of gun violence. I wanted to find out more. I wanted to tell this story.

But at the time I was still new to video. I had started at The Post as a photo editor and after a workshop and a fair amount of following the other video journalists around to learn how they did their jobs, I transitioned to my current position in early 2008. I still thought about the wheelchairs idea from time to time, but I felt ill-equipped to tackle something so complex that could potentially put me in some dangerous situations. I didn't really know where to start. So, for several years, this idea stayed on the back burner.

But in the summer of 2011 I worked on a story with Theresa Vargas about this stuff called Mumbo Sauce. It's a tangy, sweet concoction that can be found in D.C. carryouts, especially of the Chinese food and fried chicken variety. Every carryout makes their Mumbo Sauce differently and native Washingtonians often pick their carryout based on who they say makes it best. Through this story and some others I worked on with Theresa, I learned that she is often drawn to the same sort of social issue and community-oriented stories that always attract me. While on the prowl for each different variety of Mumbo Sauce, Theresa and I drove through my neighborhood, as well as through many of the other poorer neighborhoods in the city. We passed a few young men in wheelchairs and I shared my old idea with her. She immediately agreed that it would be a good story and said she was on board for doing the writing.

We pitched the story to our editors, and they were on board. Most of the time I just shoot video, but I have a background in stills. I studied photojournalism at UNC and would shoot stills on assignment from time to time. Since this was a project I pitched and cared about so deeply because it's an issue that impacts my own neighborhood, I really wanted to make the video and the stills. I talked with the photo editors to make sure they were in agreement and Theresa and I started planning the project.

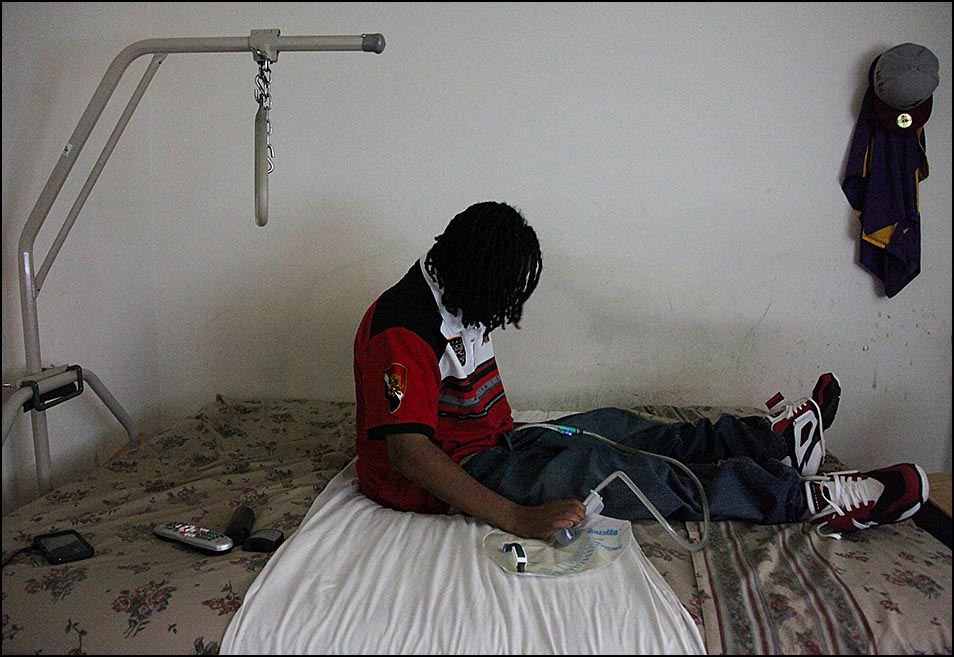

After a lot of conversation and research, Theresa identified the Urban Re-Entry Group at MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital in northwest D.C., which is a support group for minorities who are wheelchair-bound due to spinal cord or brain injury. Almost all of the men we encountered in the group were young, black males who were victims of gun violence. My theory, for better or for worse, seemed to be correct. These men opened up to us pretty quickly. They let us sit in on their group meetings each Tuesday afternoon and many of them let us come home with them to see what life is like apart from the group.

We met 26-year-old Alfonzo Moore who had just been shot a few months before we started attending group meetings. We saw how he struggled to build the strength to push his wheelchair on his own, hold a can of soda and feed himself. We got to know Corie Davis, who goes by Uni, who had been shot in 1999. He's the determined, self-sufficient old-timer who, in the group meetings, would always push Alfonzo to never give up. We spent time with Ismail "Ish" Watkins, who had been in the group even longer than Uni. The two had been rivals who hated each other in high school, but their time in the group together made them see each other as brothers. Ish has more mobility than most of the other men, and he has taught himself to walk again with the assistance of a walker. He tires easily and therefore struggles with this a fair amount, but he's the optimistic type who never gives up.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot, or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

WHITNEY:

I reported on this project for almost six months, so there were a lot of shoots involved. I really started this project when I went to an Urban Re-Entry Group meeting for the first time. I didn't bring any cameras. I just showed up, listened, and met some of the guys. This is something I often do when a story is sensitive in nature and when there is enough time so I don't have to rush. I came back to the next group meeting with two Canon 5Dmkii's, a tripod and a Marantz. I carry a lav kit and snap Sennhesier shotgun microphones on the cameras. That's essentially the kit I use most of the time. When it's interview time, I also bring along a softbox. But during that second visit, I just recorded the group meeting. I would roll on a wide shot perched on the tripod for much of the time and wander around to get tight shots.

After a couple of visits to the group, I started to visit Alfonzo Moore during his therapy sessions at the hospital. He was still a patient there, which made him easy to access. I attended some of his physical, occupational and recreational therapy sessions before he was released from this hospital. I interviewed him in the hospital as well, and learned that his brother had been shot and killed when Alfonzo was a young boy. The cycle of this violence just seemed so real and consequences so far-reaching with that fact. Later, I would learn that the same thing had happened to Deonte Gay's older brother when Deonte was a boy.

And then when I met Deonte, I knew I wanted him to be part of the story as well. He doesn't have a record, he seemed to be a hard worker and was the victim of a random crime. The other guys had somewhat more complicated stories, some with criminal backgrounds. I knew many people in our audience would see them and say they got what they deserved. And if you read the comments on the article, it seems that is the conclusion some people did come to after all. But I wanted to show that these shootings also happen to people who are just at the wrong place at the wrong time.

All the while I continued to go to weekly group meetings. I saw how Dr. Samuel Gordon got these men to talk about the challenges they face, and how he let them coach one another through tough times. There are hours of footage from those group meetings that were not used.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working on it?

WHITNEY:

Initially, I thought it may be challenging to get these guys to open up to me. After all, I am a little white woman who has very little firsthand knowledge about growing up in a rough area as a minority when the odds are stacked so heavily against you. But that wasn't really a problem. They opened up to me pretty easily.

But most of these guys aren't very good at remembering appointments. They're not glued to their Blackberrys and iPhones like all of white collar D.C., and their immobility means they have to rely on rides from others. There were several occasions when I had made appointments to meet them at the hospital, and they just didn't show up. Alfonzo's wife wasn't on board with being in the story and didn't want us to come to their home. After many conversations with her, Theresa and I managed to convince her that we really needed to see what life was like for Alfonzo at home after being released from the hospital. But when we showed up at his apartment, no one answered. We stood in the hallway of his building, which is located in one of the more crime-heavy parts of the city, and knocked and knocked. It was summer time and so very hot. Theresa was 8 months pregnant.

It had taken so much for us to convince his wife to let us come that we didn't want to give up. Alfonzo was the only one in the group who is married. And he got married after his injury. I thought it would be really powerful to show his relationship with his wife. We knocked for about 45 minutes before we retreated to a fast food restaurant down the street. After about an hour, we came back and knocked for another half an hour. We had called his wife and she said Alfonzo should be inside, though she was at work. We thought we heard rustling, but no one ever answered and we never got inside. That footage, that I had wanted so badly, just didn't happen. And that was immensely frustrating, but there was nothing I could do about it.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

WHITNEY:

Well, in this case, since I didn't get the footage, I just had to move on. Ish lives with his mother and his extended family comes around a lot, so I used that as a way to show family interaction in the piece. And there was so much ground to cover with this project that not having that material meant that I could just focus more on other parts of the story.

In the case when people wouldn't show up for appointments, there wasn't much I could do about that either besides make more appointments. I became pretty consistent about calling the guys before our appointments to confirm our meetings. And eventually I got most of what I needed. I knew just getting there was a big challenge for these guys, so as frustrating as those incidents were, I just had to let them go and move on.

TID:

How did you decide to structure the video the way you did?

WHITNEY:

There was so much material by the end of this project that the editing process was pretty overwhelming. I started the edit with several different beginning sequences before settling on one. My editor, Jonathan Forsythe, really helped me narrow down the start. And once I had that, I used the group meetings as the thread that kept the story going. I weaved the personal stories around the group meetings, and tried to use their quotes as transition points. Once I had a rough idea of the narrative, I wrote the narration. I pretty much always write the narration near the end of editing because I want the narration to play off the quotes from the subjects. I want to be sure there aren't redundancies and that it all flows nicely together. I was also lucky that our managing editor, John Temple, wanted to be so involved in the project. He looked at the video several times throughout the editing process, even during it's rough beginning, and gave me feedback along the way. That was especially helpful because when it came time to promote the video on the site, he was really instrumental in making sure it got a lot of play.

TID:

What surprised you while working on the project?

WHITNEY:

I suppose this shouldn't surprise me because it happens all the time, but I was shocked by the number of hateful, judgmental, racist remarks that people made in the comments section after seeing the story. Many of these guys are far from perfect, but their lives are really, really tough. I would never want to wish their fates on anyone. As a journalist, I always try to be objective. I know that's what we all are supposed to do and it's what journalists say all the time, but I mean, I really try. Even after spending as much time with them as I did, I still can't even come close to imagining what their lives must really be like. How hard it must be. And I can't imagine what it's like to be raised in the midst of a culture that is so laden with gun violence. It's surprising that this outcome is so unsurprising to many of these men in this situation. It's so very common to them. They can all count numerous friends and acquaintances who have been murdered. They are stuck in a cycle of poverty and crime and it's all happening here in our nation's capital. It's heartbreaking.

I was also refreshingly surprised by the amount of time our editors gave us to work on this project. The Post is known for its politics and government coverage, and not so much for enterprise stories about crime and its aftermath. But they really let us invest a lot of time in this, and I'm so grateful for that. This isn't a story we could have told well quickly. They also gave us Sunday A1 space with lots of color photos inside the newspaper and plenty of online promotion. It felt tremendous to have so much support.

And another great, surprising thing that happened was the incredible amount of access we got from MedStar National Rehabilitation Hospital. Anyone who has worked on a story that involves dealing with a public affairs representative knows that it is often a painstaking, difficult process to get the exact access you need. But Derek Berry, our PR contact there, was just really fabulous letting Theresa and myself come whenever we wanted over the course of many months. The lesson I take away from that is to cultivate relationships like that. Go after stories where access is granted instead of constantly fighting against the odds. I know that isn't always possible, but there are so many stories out there and there people who want to help you tell them.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of working on a project like this?

WHITNEY:

I learned that I can pull off a video story and a photo essay if I'm given a sufficient amount of time to do so. I don't think it makes sense for a visual storyteller to do both during quick turnaround assignments, but it is possible to do it well in situations like this. As someone who loves still photography but doesn't have a whole lot of opportunities to do it at work, it felt good to pull that off.

I also learned that when I have story ideas, even if they may seem complicated or difficult to tell, I need to pursue them. People will have my back and if I really dig in, I can tell those stories.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

WHITNEY:

If you're shooting both video and stills for a project like this, start by carefully planning when you will shoot what in which medium. It's really important to get strong video sequences. Shooting stills can interrupt that if you aren't focused and thinking about what you've got and what you don't. Sometimes it helps to go into a situation saying you will only shoot video or only stills that time around, and then switch it up for the next scene. I keep a running list of what scenes I do and don't have recorded so I won't forget what I still need in the midst of such a complicated process. I map out the story in outline form pretty early on so I can see how the scenes I have and the ones I want to get may potentially fit together.

Also, I'd say that listening is the most important thing to do. I think that's probably why these guys trusted me so much, because I listened to them and I didn't judge them. I also had to be very patient, as is probably clear from what I said earlier about the times some of the guys would miss appointments. Sometimes there is a lot of waiting involved, and letdown when someone doesn't come through. I had to walk a fine line of being persistent with being patient and forgiving.

And finally, when it comes to a story like this where a lot of the scenes occur in tough neighborhoods, it's important to be safe and trust your instincts. I went to a lot of their homes by myself but I made sure to do so during the day most of the time. I always kept my gear on my body. And I was friendly and said hello to people I crossed paths with. No matter where you are, I think that goes a long way.

:::BIO:::

Whitney Shefte is a Peabody Award-winning video journalist at The Washington Post, where she has worked since 2006. Whitney pitches, researches, reports, shoots, edits and produces multimedia stories for the Post’s digital and print platforms. She has documented everything from AIDS in D.C. to traumatic brain injury in the military to life in India. Whitney serves as an executive board member and is on the video and multimedia committees for the White House News Photographers Association and is an active member of the non-profit organization Women Photojournalists of Washington. A two-time regional Emmy Award winner and two-time national News & Documentary Emmy Award nominee, Whitney received a Peabody Award in 2011 for her project "Coming home a different person" on traumatic brain injury. She and a team of other Post journalists were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting for the same project in 2011.

Whitney is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Journalism and Mass Communication where she concentrated in photojournalism. She grew up in the Charlotte, NC area, and despite many years of loss and heartbreak, she remains an unwavering Carolina Panthers fan. When she isn't working, Whitney enjoys rock climbing, practicing yoga, exploring the outdoors and traveling. Follow her on twitter @whitneyshefte and see her work at vimeo.com/channels/whitney.

If you want to see more of her work you can go here: