Spotlight on Thomas Franklin

Dec 16, 2011

Originally published 12/16/2011

TID:

Thanks so much for your time. Please tell us a little of the backstory of this iconic image.

TOM:

I worked for the the Bergen Record newspaper at the time. Our offices were in a five-story building in Hackensack, NJ, five miles from New York City. I happened to be in the office early that day preparing for a meeting when an editor came running into the photo department saying a plane had hit the World Trade Center.

Immediately I knew that was no accident. Living in this area all my life, I just knew that didn't happen by chance. I ran over to the window, looked across the Meadowlands towards lower Manhattan, and saw a tremendous amount of smoke coming from the North Tower.

I ran down to my car and started driving towards the Lincoln Tunnel, heading towards New York City. It was crazy. I was listening to the live reports on the radio, and as I'm driving down the NJ Turnpike, I heard that a second plane hit. I'm thinking, "Holy Shit!"

The bridges and tunnels into the city were now shut down, so I continued driving south towards Jersey City. I must have been doing 90 mph at this point. I make it to Exchange Place, a financial district with tall buildings and a bustling downtown located on the Jersey City riverfront. As the crow flies it's maybe a half a mile from the World Trade, just across the Hudson River. It's also a ferry port for commuters. Short of getting into NY, it was about the best location for shooting what was happening.

That's where I made pictures all morning. I stayed there until I eventually got kicked out by the police a few hours later. There were thousands of evacuees coming to NJ by boat; some were injured, most were covered in dust, it was very chaotic. A triage center was set up there, and people were being treated and others were being rushed to ambulances on stretchers. And you had all of this happening with the backdrop of the New York City skyline billowing smoke. It was very dramatic.

I made images of bloody victims. There were pictures of people looking bewildered, people openly crying. I remember working quickly, as the police and others were trying to keep us (the photographers and media) away. At one point I got shoved by a cop, jarring my Canon D2000, permanently corrupting my digital card. I lost about a hundred images on the card and lost the use of that card from that point on. Remember, in those days we only had 256mb-512mb cards, unlike today were we can shoot almost endlessly.

I was still in Jersey City when the towers fell, seemingly without a sound. I was thinking there must tens of thousands dead. And what about my colleagues? Surely some of them were there, perhaps inside the fallen towers. It was a frightening thought. I remember thinking how apocalyptic it all was. It was unimaginable that those two towers could come down that way, and that they were no longer there.

TID:

What did you remember feeling at that point?

TOM:

I certainly remember the rush of adrenaline you get when working a big story, but mostly I felt concern for family and friends who I knew worked down there. My older brother worked near the World Trade Center, I knew for sure he would be affected - I learned later that he was OK, hunkered down in his office building - and I'm running through my mind all the people I've known over the years that worked there. I knew many.

As I'm thinking of all these people, I'm trying to stay focused - that was the biggest challenge for me. I knew what I was doing was important, but I didn't want to become emotionally-impaired either. Clearly I was documenting history, that was foremost in my mind. In a way, working the story and photographing kept my mind from wandering about the personal connections and the long-term ramifications of what was happening.

I had little or no factual information that day. We were hearing rumors like that the White House had been hit. I wasn't sitting in front of a TV like most of America, and cell phone communications were practically nil. Throughout the day, I was going on information I heard on the street. Much of it was wrong.

One of my main concerns throughout the day was getting word back to my wife, who was at home with our young son. I knew she'd be worried about me. Briefly I was able to get a call through to an editor. I asked him to tell her I was OK, and to ask her to find out information about my brother. I told him also not to tell her I was in NY.

TID:

What happened next?

TOM:

A series of things happened. Around noontime the police kicked out all the media at Exchange Place, as they were trying to evacuate the area. I had been there from about 9:20am - noon. By then, the second tower collapsed and subsequently the evacuation had stopped - I don't think there were many survivors or evacuees coming across the river at this point. I went back to my car to transmit some pictures but couldn't because there was no cell connection. So I made the decision to try to get into the city. That's where the story was and I wanted to get as close as I could. I wanted to see it.

I walked back to the riverfront. It was now 45 minutes later and I was able to blend into the crowd. I put my camera in my bag and I got behind police lines. I then bumped into John Wheeler, a photographer friend, who said he knew the head of the Jersey City Police Department there. So together, we approached him and within ten minutes he put us on a boat heading towards Manhattan. At this point the smoke cloud was large and dense. I remembered thinking, "What am I going to see? Am I going to see dead bodies?" I reminded myself that I needed to stay focused on my job and make pictures. The tug boat captain then handed me a bottle of water and a paper mask.

At this point, I had almost been arrested twice back in Jersey City, so I decided to play it cool and get a lay of the land before heading directly in. I walked around to the north and tried to enter from there. I made some images over by World Trade Building 7, a tall, pinkish, building on the north side of the World Trade Center Plaza. It was still standing at that point (it later collapsed, shortly after the flag-raining image was made). I shot some images from there of firemen dousing the smoldering wreckage, but I couldn't get into the center of Ground Zero from there, the police had it blocked off.

WTC 7 looked stable from the side I was on, I was a mere dozen feet or so from the base of the building, but unbeknownst to me it was badly damaged on the opposite side - the Ground Zero side. I remember a fire officer then came running over to me, screaming to get out of the area. "Get out of here!" He said, "It's dangerous!" He then had me escorted out by police and warned me not to come back, threatening arrest.

But I knew I had to get inside the perimeter, so I circled back to the west and walked through a dense smoke cloud over by Pumphouse Park, near the World Financial Center. From there I was able to get into the epicenter where the two towers once stood. Only now it was a vast landscape of mangled metal and debris. That's where I spent the next couple of hours shooting.

The wreckage was so vast it was hard to focus on any one thing, or to capture the scope of it all. I remembered making pictures of mounds of smoldering metal piled high. Everything was gray, there was no color, the landscape was unrecognizable. Everyone I saw was in shock. It looked like a battle scene from a movie, smoke and dust everywhere. Firemen were in search-and-rescue mode, without any rescues. It was apparent to me that there were no survivors. I didn't see anybody being saved.

At this point I'm doing OK emotionally, I was never concerned about my safety. I was mostly concerned about making pictures quickly and effectively, without drawing too much attention to myself.

TID:

So at this point, you had good access?

TOM:

At this point no one even noticed me - strangely. It was like getting to a serious spot news scene before the police and fire department arrive. It's so real and present that nobody notices the guy with camera. It was like that. I had unfettered access for a short while, and I shot a large volume of images in a short amount of time. I went into adjacent buildings, which was spooky. I climbed over shards of metal trying to get closer to the search and rescue, I walked the edges of the fallen debris. At one point, I stood in ankle-deep water.

There were thousands of people presumed dead - I was the least of their worries.

At around 4:30pm, word spread that WTC 7 was going to collapse (the same building was I standing near a few hours earlier) and they halted the search and rescue. Everyone migrated west of the World Financial Center. A first aid center was setup there and hundreds of fire, police, and rescue personnel gathered. I remembered it being really quiet, kinda solemn. Like a wake.

At this point, I had nearly filled up my flash cards - well over 1,200 images. I even started deleting images to make more room. The cards were crap compared to what we use today. They were slow to write to the disc, temperamental, plus they only held a few hundred images each. Plus, one of them malfunctioned from the police incident earlier. I think back now about how crazy that was, deleting images under pressure like that... Who knows, I might have lost some good images.

It's almost 5 o'clock, and I'm a world away from my computer and my office. I figured I had roughly enough space for 50 more frames. I decided to walk back into the Ground Zero area. It was there that I saw the three fireman about 100 feet away, standing up on a rise. I saw them doing something with an American flag.

I positioned myself and called over to another photographer I had just been talking to, "Hey, you might want to look at this." A moment later I see the flag going up. I shoot a quick burst of frames. Then it was over. There was no performance, they didn't do it for any audience. No words were exchanged.

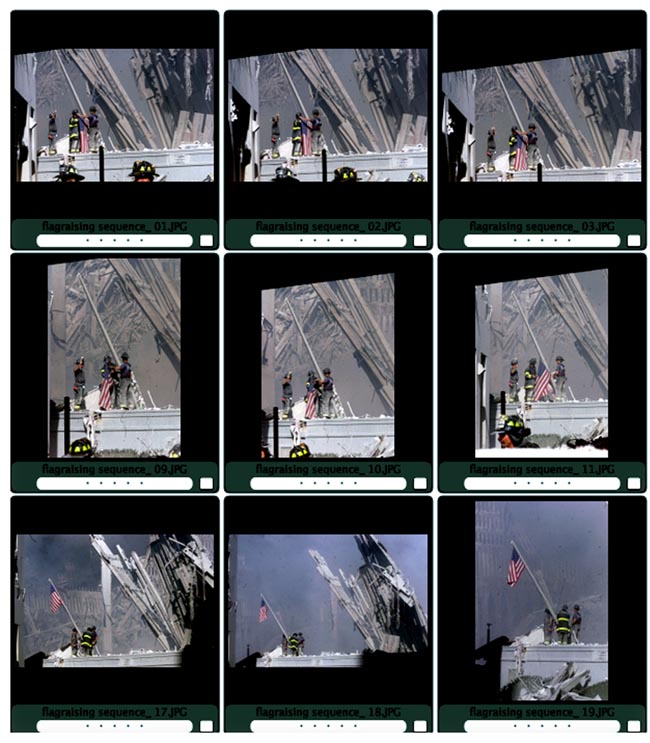

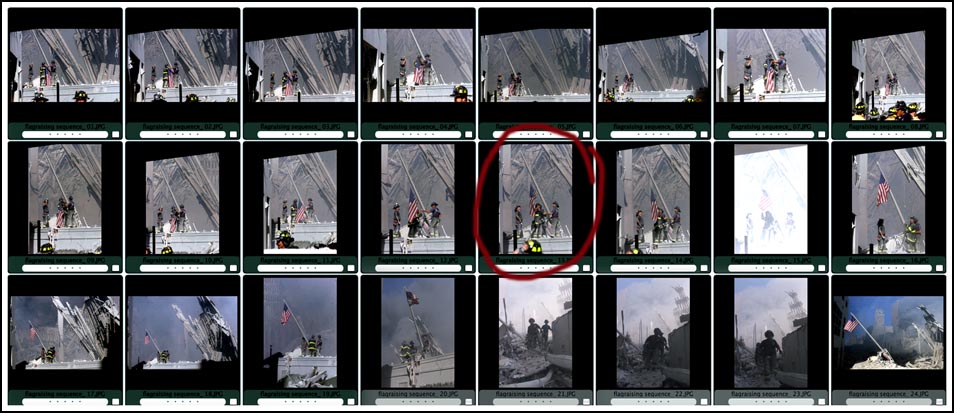

I think I shot about 24 frames over a two minute time frame, from the moment I first saw them to the moment the flag went up. I shot it with a 70-200mm, with a converter. As you can see by the image, there was a ton of crap caught inside my lens and camera.

The question everyone asks is, "Did you know what you had?" The answer is - no way. At the time, it didn't stand out to me. Three men raising a flag did not seem very important to me at that time. Two of the largest, most recognizable buildings in the world came crashing down on thousands of innocent people. What happened seemed apocalyptic... So how could this act even compare?

I mean, I clearly recognized the symbolism of what they were doing, and it momentarily dawned on me that it looked familiar (like Joe Rosenthal's famous Iwo Jima image). But in no way was it constructed that way. It happened more like a play in sports, you have a brief moment or two to size it up, position yourself, compose it, zoom in or out, and press the shutter.

For me, there was no time to make an image that was any different than the one I made.

It should be noted that there were two other photographers who made pictures of the same moment, unbeknownst to me at the time. Ricky Flores, a friend of mine who shoots for the Journal News, and Lori Grinker. They made very similar images from the same location, from above the site looking down. Both made very powerful pictures.

I then saw the firefighters climb down. I walked past them and they walked right past me. I climbed up onto the rise and made some wide angle pictures of the flag and the wreckage behind it. At this point I was done. I had no more space left on my digital cards, it was getting late, and I had to figure out how I was going to get back to my car and my laptop to transmit. It then took me a long time to talk my way onto a boat; I guess I was not essential personnel and no one wanted to take me. I finally got on a police boat that took me back to New Jersey - it was getting dark.

The problem was, I had been brought down to Liberty State Park, a few miles from my car - not where I needed to go. When I got off that boat, the police had a decontamination center setup, with long lines of people waiting to be hosed down and screened. I said to myself, "No way I'm going through that." I needed to make deadline and I didn't have time for this. So I made a run for it, like in The Fugitive. I bolted from the line and ran across an open field towards the parking lot, sprinting all the way.

I then hitched a ride with a woman who had just dropped off her husband - a Jersey City firefighter heading into Ground Zero. I asked her to take me as far as she could in the direction of my car. Turns out she escaped the World Trade Center early that day and showed me the gash on her leg. I remembered we both got emotional talking about what we saw. She ended up taking me all the way to my car. A kind, thankless act for which I was grateful. I never even got her name.

Finally, I got back to my car, but cellular service was still out. So I attempted to make the 20 minute drive back to my office. I got about halfway there before coming upon a massive traffic delay. (I found out the next day that there was police action going on; they thought they caught some terrorists but it turned out to be a false.) So I drove over a divider, exited Route 3, and pulled into a Ramada Hotel. I set up in the lobby, plugged in, and started working from there.

I was sitting near the hotel bar, and as I'm editing my pictures a crowd of people started huddling around me, looking at my pictures as I worked. At the same time, I'm catching my first glimpse of the horrific images of those planes crashing into the buildings playing on the TV screen in the bar. It was my first look at the imagery, it was shocking. I pressed on with my editing.

I moved 31 pictures. I was editing, captioning, sending, editing, captioning, sending... Remember, the flag raising was one of the last pictures I made, and since it didn't stand out to me, it was one of the last pictures I moved.

A short while later, I got a call from my photo editor Rich Gigli who wanted to know more about the flag raising picture. "What's going on here?" he asked. I told him they were raising the flag, and it happened very quickly, I didn't have many details. I asked him what he thought about my other pictures, but he was fixated on that image. He said, "We really think it's very strong."

After I finished editing, I drove back to the office. When I got there, there were hugs and storytelling with some other photogs, all of whom had unique stories to tell about what they saw and shot. But everyone was talking about that picture, and I kept asking, "Why? What about all the other pictures?"

Gigli sent the picture to the Associated Press in the early morning hours of the 12th. It was still early enough for papers on the west coast to pick it up. That's really what started the popularity of the image. By the time I got to the the office early the next morning, they told me the phones were ringing off the hook. I remembered thinking how odd that was. The paper started bringing people into the department to handle the volume of calls and emails.

I went out and shot some assignments; I remember shooting security at the George Washington Bridge, and later a Port Authority cop who narrowly escaped the falling towers. But by that afternoon, Gigli told me to come back to the office and help handle the barrage of requests: for licensing, charity usage, commercial uses, reprints, and interviews. Clearly people recognized immediately that there was commercial value to the image. It became overwhelming very quickly, and we couldn't handle it. I started making calls to photo agencies. By the end of the day I negotiated a deal on behalf of the newspaper, which owned the image, for handling the usage. We came to an agreement with Saba.

I can remember waking up on Thursday of that week, and my wife was watching "The Today Show," I think it was. Someone was holding up the NY Post with my image on the cover (no credit given, by the way) and talking about my picture. It felt very strange. Then on that Friday, I think it was, they had me on "The Today Show." It was the beginning of a whirlwind of attention. It was pretty crazy.

That day and for the next few months it became a balancing act of trying to do my job while trying to accommodate the requests for the picture and my time. It was stressful, and it became bittersweet because the image was receiving a lot of attention, yet at the same time there were thousands of people dead - hundreds in our readership area alone. It was an emotional time.

There was an immense sense of loss, a sense of loss that lasted for a long, long time, and still exists for many. Very early I separated myself from it. It wasn't about me, it has always been about the relationship people have with the picture. Photography is so much about the feeling people get from looking at an image.

To me, this picture is about thousands of innocent people who were murdered and died in the most horrific way imaginable. Innocent people, who died senselessly. Any discussion about 9/11 has to be about that first and foremost. I believe that.

I don't feel defined by this picture, I'm not sure it's the best picture I've ever made. I don't even know if it's the best picture of that day. But clearly it's the most meaningful picture I've made. It's been used on a postage stamp and helped raise over ten million dollars for families of victims of 9/11. Even ten years later, I still get letters, phone calls, and emails about it. To me, that speaks volumes of the power of a picture. And this picture has lived a life of its own. It went viral, and it was used in a way that did a lot of good. That's pretty cool.

I don't spend a lot of time thinking about it though, or dwelling on it. I think I did great work before then, and I've certainly done some great work since then. In many ways it seems like a long time ago.

TID:

You said at one point, "For many the image has become a symbol of the tragedy of that day, it was something that just happened. A moment to which I was a witness. I shot it the best I could and then moved on." Could you elaborate?

TOM:

I'm not a big anniversary person. What's the difference between nine and ten? I don't think it feels any different for those who lost a loved one. The events of 9/11 have certainly changed me, though. I think it's changed everyone, especially in this part of the country where the attacks were so personal. Many like me in the NY-NJ area felt so violated.... and by a wayward group of cowardly attackers. And even now, the sense of loss is tremendous.

TID:

What do you most want people to know about the process of making the image?

TOM:

I think all good photojournalists have a desire to get closer in order to make better pictures. I suppose I could have packed up and gone back to the office a few times that day, I certainly had some very strong images to hang my hat on. And emotionally and physically, I might have been better off not having seen all that I saw, and being exposed to the elements. However, I still stayed with the story. I made it to Ground Zero that day by being dogged. And it payed off. Many could have made that picture, but I put myself in that position. I recognized it and I got it.

TID:

Where has the image appeared that surprised you?

TOM:

In some CRAZY places for sure. People used to send me stuff, I mean crazy stuff. Clocks, wristwatches, seat covers, chocolate bars, pumpkin carvings! Friends still send me pictures when they see it in strange places, I have quite a collection. For awhile, "entrepreneurs" would send us prototypes of items they wanted to market, stuff like statues, trinkets, light fixtures, paintings, etc. Lots of chatchkas.

TID:

You mention it has "raised over $10 million." I'm assuming since the verb is "raised" and not just "made" that at least part of those funds went to charities or foundations. Can we have more information about that?

TOM:

The North Jersey Media Group, which owns the Bergen Record, owns the copyright of the photo. They have used the image in many ways to raise money, which then has been allocated to aid certain NJ families affected by 9/11. The "Heroes" stamp, which is a semi-postal US Postage stamp (semi-postal stamps are stamps where proceeds are used for charity, like the Breast Cancer stamp) features the image, and has raised over ten million dollars by itself. Those funds I believe were controlled by FEMA and allocated to 9/11-related victims. I believe that some of the funds leftover were used to aid Katrina victims.

TID:

You mention the Rosenthal reference, but one of the big differences in context with his photo was that it was taken during a war. Any thoughts on why your image being shot on American soil resonated so much with something that happened thousands of miles, and decades apart?

TOM:

Well, there's the obvious visual similarity, which (as I previously mentioned) was mere coincidence. And 9/11 was like a war, and the firemen (and police and other first responders) were the soldiers.

One of the reasons, I believe, that my image resonated with so many was because it was viewed largely as a symbol of patriotism, pride and strength. A seemingly positive image, on a day where nearly every other image made pictured death and destruction. Again, a photo can mean different things to different people.

TID:

I also remember hearing you and Joe having some conversations and making some jokes about your images. Do you care to share any of those exchanges?

TOM:

That was great, I'm glad you mentioned that. Joe was photo royalty, a really sweet man. We spoke on the phone one time at the Eddie Adams Workshop over the PA system, after I gave a presentation. Joe and Eddie were old friends, and Eddie arranged the call to Joe who was all the way out in California (only Eddie could pull off stuff like that!) It was a great experience for me. Then the following year, Eddie and Nick Ut brought Joe up to the farm and we talked awhile. I wanted to ask him for a signed photo, make a trade, but it didn't feel right so I didn't. Joe has since passed away, but I remember our meeting fondly. However, he didn't reveal too much, I just assumed he was long-tired of telling the same story. I can't blame him.

TID:

How do you think your life would be different if you hadn't made the image?

TOM:

I don't think my life would be much different at all. I'm still doing what I love, I'm still telling stories with images, only now I work primarily in video. I don't think making the picture has changed me at all. I just always try to be true to myself. I think as a photojournalist you let the pictures do the talking. I just try to stick with that.

Tom was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for his 9/11 photographs, and has won numerous national and international awards. His flag-raising image has appeared on the covers of countless news publications. Life magazine listed it as one of the "100 Photographs That Changed the World," and the photo is part of the permanent collection of the Library of Congress. Tom has been on staff at The Record, Bergen County, NJ since 1993. Presently, he is a Multimedia Editor and video producer for the paper’s website, NorthJersey.com.In 2005, his documentary film Ford's Toxic Legacy, was the winner of the New Jersey Film Festival's Best Jersey Film award. His documentary work has helped expose toxic dumping by the Ford motor company and its ill-effects on the Ramapough Indians, and the environment. He is also a professor of photojournalism at Ramapo College, and graduate of Purchase College, in Purchase, NY.

++++

Please note that TID does not hold the copyright to any images featured on our site. Any duplication of images must be done so with written permission by the photographer or the copyright holder. TID can, however, make every attempt to put you in touch with the holder in an effort to license and reproduce the image.