Spotlight on Theo Stroomer

Feb 11, 2016

TID:

Thanks for being open to this, Theo, can you tell the back story to the image and project?

THEO:

Hey Ross. Thank you for the opportunity to talk about my work.

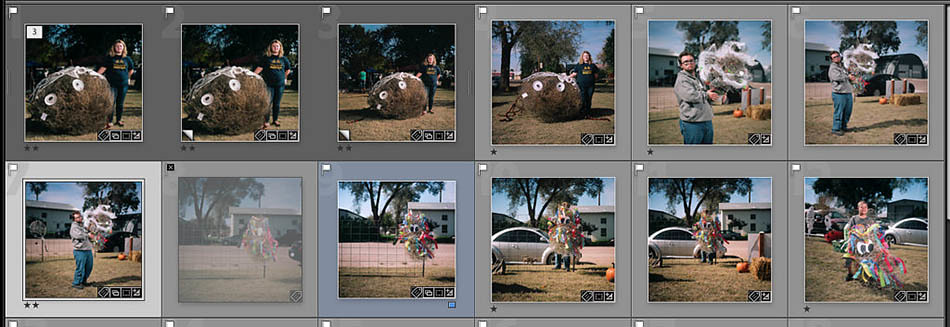

My image is from the 8th Annual Haigler Tumbleweed Festival, an event in Nebraska. The guy in the photo is Jesse Jenkins. He was one of the competitors in their tumbleweed decorating contest. Haigler is this tiny town near the Nebraska-Colorado border; after their community got buried in tumbleweeds about a decade ago they decided to start a festival. It happens often, actually – stuff getting buried in tumbleweeds. My project chronicles this phenomenon and, more broadly, is about our relationship with drought and a changing environment.

I started thinking about it almost exactly two years ago. In early 2014, I was having breakfast with my friend Sarah Gilman. She mentioned she had just written a short piece about tumbleweed problems in southeastern Colorado. I poked around and found that relatively little had been done on this. Her article, and some local TV news pieces, that's pretty much all I found when I searched the interwebs. They didn't send a photographer for her story. I found a few newspaper blurbs, some random stuff on Getty, and National Geographic's fantastic piece on tumbleweeds in December 2013 – with photos by Len Jenshel and Diane Cook. That story became an inspiration for me, but I decided I had a different angle and I wanted to pursue my own project.

Then it was a matter of figuring out how to locate tumbleweed attacks when they happened, along with researching and photographing the less time-sensitive parts. I sat around and thought about it, and sorted some logistical details out (which I'll get into later.) When tumbleweed season hit later that fall, I was ready to drive out to start photographing.

TID:

This project was self-generated and had a unique angle to it; can you talk about your motivation to explore this?

THEO:

When a topic speaks to me, it feels like a buzzer going off in my head. I just know immediately that I am connected with it (I recently heard Phil Toledano speak and he described this as his internal tuning fork, which is a great way to put it.) That's how it felt when Sarah started describing the article she was writing.

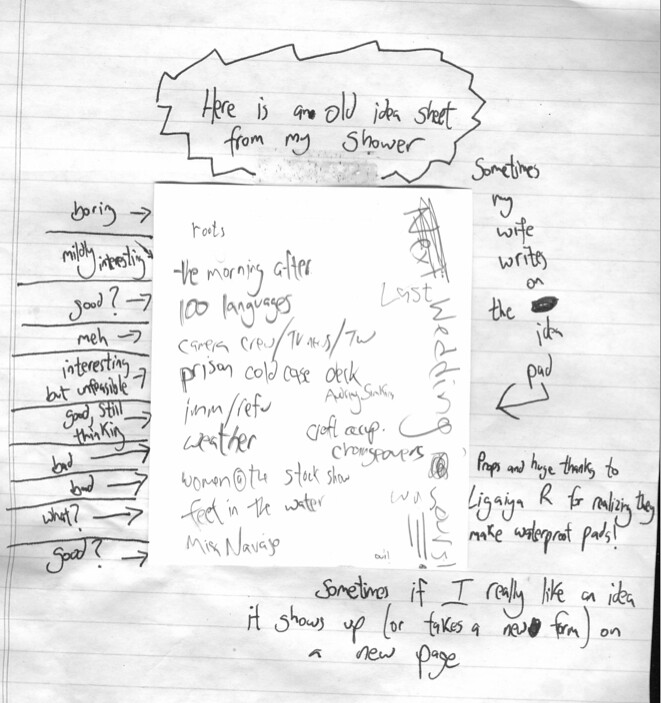

I'm interested in stories around Colorado, where I live. I am fascinated by representations of the American West, and how art often ends up wallowing in the stereotypes of that genre (I'd like to see more photography buck this trend.) This story has an environmental bent as well, so it ticked a lot of boxes for the stuff I'm into. Even when I feel excited about a project, things take time to gel. I do better when I write ideas down (especially in the shower, total #1 brainstorm spot) and revisit them.

This one started with a YES! ME! vibe, then I researched and still couldn't get it out of my head, then I started to figure out the logistical nuts and bolts, took a few initial pictures, and finally stuck with it as I realized that my idea was working and I was enjoying the experience. I'll know I am done when I stop feeling that way. Every project is different, but they all come from some version of a process like this.

TID:

What sort of planning did you do in preparation for this project?

THEO:

I knew that tumbleweeds had buried spots in Colorado and New Mexico during the past few years. I suspected it would be happening again. I started looking at how/where to predict high winds, and how to track what other people were posting on the Internet when their towns got hit. I also emailed Len and Diane (who did the Nat Geo photo essay) and they generously wrote back with some tips about their own experiences chasing tumbleweeds.

I was thinking a lot about environmental disaster coverage – not that tumbleweeds are a disaster, necessarily, but as a reflection of my own work. Palíndromo Mészáros has a project called The Line that I was influenced by too. I started out using local forecasts and Wolfram Alpha to scour the web. It was too time consuming. Eventually, I found a site that does visual wind forecasting called windyty.com . I started using Google Alerts for tumbleweed news, and I set up recipes using If This Then That to email me whenever someone mentioned tumbleweeds on Instagram or Twitter.

Now, during tumbleweed season (late fall to early spring) I wake up, check the wind forecast for the southwest, type 'tumbleweed' into Facebook to see what people are posting, and then look at my tumbleweed inbox for social media mentions. I have to filter through a lot of irrelevant posts (the inbox has 12,000 emails) but it's managable and has led me to some solid pictures. When I started, I was imagining photographs of things getting buried. I have ended up taking a broader approach and trying to contextualize the phenomenon.

TID:

I’m always curious how people express themselves in situations like this. How did you normally approach people and convey what you wanted to do?

THEO:

Be honest while communicating that you're passionate and well-informed. This opens a lot of doors. Ross, you and I met at TID two years ago (there's my almost-shameless workshop plug) and you described it in a way that totally resonated with me: Tell people, “I'm so-and-so and this is my purpose!”

I think it's ok not to have all the details at the beginning. I told folks that maybe I would end up doing a tumbleweed book, but I wasn't sure yet and for now I was just taking pictures because I was interested in the topic. Now I have work to show and that makes it even easier to communicate my intentions. I usually offer to share prints or email images to my subjects. Another bit of advice I love and try to live by comes from Gay Talese: show up in person and be well dressed. That doesn't mean I never use the phone or email, but sometimes they aren't appropriate.

When I started, I would call city hall in bumf*ck and ask if their town was buried in tumbleweeds. “Just how bad is it ma'am?”

I would get these understandably suspicious, weird responses. When I hopped in my car and drove out, people took me way more seriously (or maybe they found it harder to ignore me in person.) I could actually meet recent tumbleweed attack sufferers to photograph, too. I paid a price for this, which was that it didn't always work out and I had wasted a day driving around, but that's just how it goes. I feel ridiculously, joyously invested in the enterprise of chasing my story.

TID:

What problems, if any, did you have and how did you overcome them?

THEO:

Most of the tough things about this project are common with self-generated work: finding time, justifying the money for a tank of gas and film, convincing myself that today's a good day to drop everything else. I have to be ready to go ASAP if I hear about a storm of tumbleweeds blowing in; sometimes it feels like I lose these opportunities because I have a paying gig that day or dinner with my family already lined up or whatever (you can cancel that sometimes, but do you want to bail every time?) I accept that I'll miss some photos, but that's ok because I can work on this as long as I want.

Only one guy has said no outright to having his picture taken. I read about him getting trapped in his house by a tumbleweed attack, and I finally tracked down his phone number and called him up. He said he had no desire to talk about or relive the experience.

Some other people have been difficult to communicate with, but I'm going to try and win them over next time I pass nearby. There is a physician who wrote a really eloquent newspaper article about a tumbleweed storm who I want to interview, and a farmer who owned a Kansas farm that sold tumbleweeds for years but I'm pretty sure went out of business. I'm hoping that if I appear in person, they will open up to me.

TID:

Can you talk about not only the lead image, but some of your other favorite frames?

THEO:

Bertha Medina removes tumbleweeds from her barn. Hanover, Colorado.

This was from the first day I shot for the project. I drove to a spot south of Colorado Springs and started seeing a lot of tumbleweeds and knew I was close to a picture. Finally I passed this woman cleaning up her barn. I must have looked especially slackjawed because it was the first time I'd seen this in person, but we spoke for a little while and I felt ready to ask if I could take some photos. She said yes, if I helped her shovel tumbleweeds afterwards so she could get to her freezer in the barn. I took the deal. She got to the fridge.

Bleachers. Springfield, Colorado.

I walked into city hall in Springfield and asked about their tumbleweed problems. The woman I talked to very generously called up the maintenance guy who had keys to the stadium and told me that's where I should go take a picture. With many of my images, advice from a helpful local about a specific location (or at least the general vicinity) was what allowed me to get the photo.

Alice Glover poses for a portrait in her home, where tumbleweeds had filled approximately four feet high in the yard. Eads, Colorado.

I was wandering around Eads and saw Alice standing in her kitchen and really quickly snapped two pictures. I was kind of far away and I didn't think they were that great though, so I worked up the courage to knock on her door and asked her to pose instead.

A controlled burn during a cleanup at Chico Basin Ranch in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

I saw a Facebook post that there was going to be a volunteer tumbleweed cleanup at this ranch. I emailed the organizer and explained what I was doing. I offered to share some photos with her and her volunteers, and she invited me to come for the day. I get to shoot film for my project, but on days like the cleanup, when I know I am going to send a bunch of photos that don't really have to do with my own visual needs, I bring a digital camera so that I can snap away.

TID:

We also talked earlier about this project, and you mentioned that you got some grant support. Can you talk about this and what advice you may have for others who want to pursue grant funding?

THEO:

Grantwriting is a pretty big topic. First off, if you are someone looking to write more grants, drop me a line sometime and I would happily talk your ear off =D

There are very few photojournalists who sustain themselves entirely with grants. For everyone else, it's just a gift that makes things easier at some point in their careers. The obvious reason for applying is the money (duh). You'll fail way more than you succeed, though. I have applied for dozens of grants in the past few years and been rejected for almost everything... but gotten a few. One was for the tumbleweeds work.

Whether or not you receive a grant, applying is a healthy process. Writing about my projects makes me look at them from other perspectives. I have to refine my artist statements. I have to figure out a budget and a timeline. I have to list photographs that I still need but haven't captured yet. This is good for my brain and, ultimately, good for my work, even when it sucks to get rejected for the 18th time. Added bonus: writing these applications makes you better at pitching, which can be another way to make money doing projects with clients you've always wanted to work with.

It's wise to be on top of the landscape for grant funding, which means using resources like the dvafoto calendar and Disphotic. You start to get a handle on grants and contest cycles, and what wins where, when you follow them for a year or two.

After saying all that: I think you have to start projects on your own. With your own time and money. That's the reality for all of the working photographers I know. Consider applying for grants once you have a solid start to a body of work.

TID:

In conclusion, what other advice do you have for photographers wanting to do this type of work?

THEO:

Listen to that voice in your head that tells you to photograph something. Your personality is a huge asset, because it makes your photography unique.

Every time I've undertaken a personal project like this one – something I loved doing, something I cared about and invested myself in - it has advanced my career while also providing a lot of personal fulfillment.

Don't rush the creative process. Ideas need time to evolve.

A strong work ethic goes a long way.

Failure is normal. I have a mental graveyard littered with bad project ideas and stuff I tried/flubbed/discarded. I think that's ok, and healthier than it feels at the time.

Friends matter. Invest in those relationships and you will find time and time again you're glad you did – friends hook you up with jobs, they give you honest critiques of your work, they bail you out when your camera breaks, and they remind you that no, you're not the only person who gets depressed and jealous and angry about the journey of being a photographer. (Also in my case, they send me a bazillion Facebook messages when tumbleweeds bury something and it gets on the news =D)

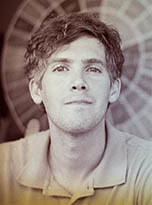

:::BIO:::

Theo Stroomer is a freelance editorial and commercial photographer in Denver. He grew up in Colorado. His personal projects explore the nature of community and regional identity, particularly in the American West.

His work has been recognized by Critical Mass, Review Santa Fe, and the Eddie Adams Workshop. His clients include the Wall Street Journal, AARP, the New York Times, Rolling Stone, NPR, and many more.

He drinks a lot of fine coffee, eats gummy bears in moderation, goes mountain biking whenever he can, and of course is a tumbleweed nerd. (Recent discovery: Did you know that some tumbleweeds in Australia are also called Hairy Panic Grass?

You can see more of his work here: