Spotlight on Susan Hale Thomas

Jan 1, 2015

TID:

This is a beautiful image, can you please tell us a little of the backstory?

SUSAN:

Thank you for the interest in my work, TID! This photo is from a series of photos I took in January 2014. These are fishermen from a small coastal village in Sierra Leone where life revolves around fishing. There’s a natural rhythm to village life—the fishermen and the village work together 24/7.

Before the sun comes up, you can hear the fishermen’s voices carrying across the water to the village. This is how the villagers wake up. They head down to the beach in the dark to help pull the catch in. By sunrise, a small crowd will have gathered around the women on the beach who separate the fish to smoke and sell. During the hottest part of the day, the men sit in the shade and mend their nets, or are busy working on their boats. At sunset, families get together for dinner.

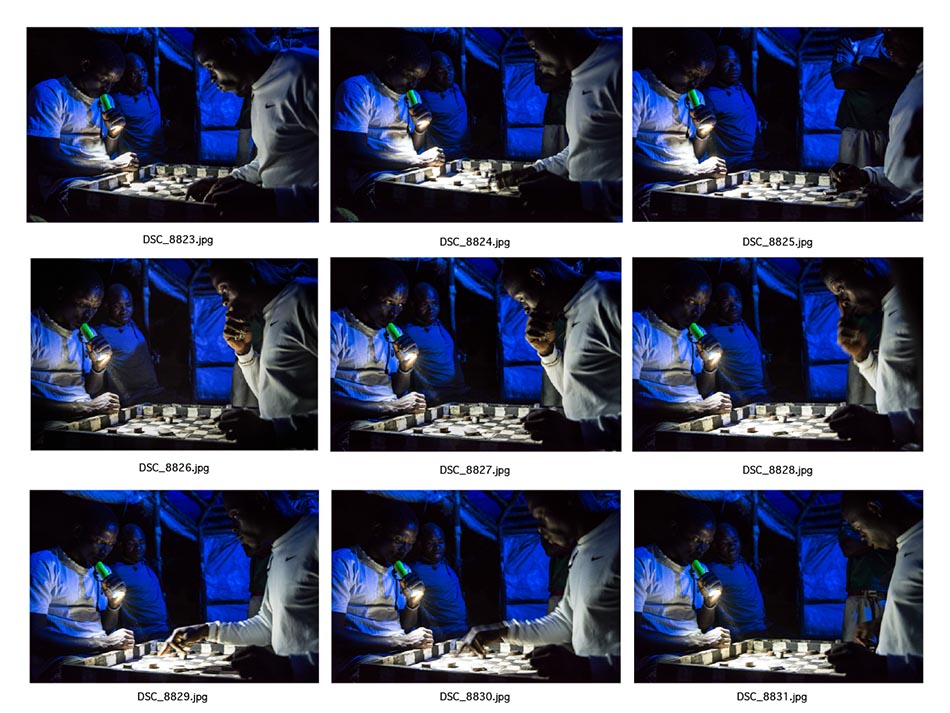

Afterward, the fishermen head over to Mr. Ali’s, a shack made of a sticks, blue tarps and two blue light bulbs. There’s usually local music blasting from a boom box and a checkers game going on. There’s a lot of homegrown pot, beer and camaraderie after the day’s work. I really don’t know when they sleep because, just after midnight, the fishermen head back down the beach to their boats. I sometimes sleep out there at night—they’re like fishing ninjas. To spot them you have to look for the glow of a cigarette. They slide their boats down the beach into blackness. It looks downright terrifying. Some of these guys can’t even swim. They work only by the light of the moon and stars. They paddle far out to the horizon, but you can hear them in the distance. They drum the sides of their boats to corral the fish into their nets.

They’ve invited me to come out with them in the canoes at night. I plan to do this the next time I’m there on a full moon. It would make for amazing pics! I’ll be taking a raft with me just in case. The canoes are very wobbly.

TID:

How did you begin the project, and what were you looking for initially?

SUSAN:

Since 2010, I’ve been traveling regularly to a small village on the coast of Sierra Leone. I got wind of a very small eco-tourism village starting up there and took such a liking to it, I built my own hut there along the lagoon. From spending so much time there, I decided to start a personal long-term project to tell their story. Sierra Leone spent most 90s locked in a civil war. The war has been over since 2002, but it took a massive toll on the country. The Ebola outbreak is pounding it even further. The country will be struggling to shed the stigma of war and sickness for some time. What many people don’t realize is the country was a destination for wealthy vacationers in the 80s. The country’s beaches are stunning.

The local fishing community is being hit hard right now economically. Foreign industrial fishing trawlers are depleting fishing stocks. They undermine the environment and are endangering the livelihoods of local small-scale fishermen. Illegal fishing is clearly visible on the horizon at night, and now the boats are so brazen, they come Sierra Leone’s waters in broad daylight. The country has few resources to protect its waters.

As a result, many fishermen are desperate for money and turn to sand mining. The mining trucks come day and night to the beaches and take the sand, although it has been declared illegal by President Koroma. The sand is being used for construction elsewhere in the country, mostly projects the Chinese are heavily invested in. Pre-Ebola, investors were pouring into Freetown. The economy was growing. Properties along the road’s path were being bought and developed, but not in a good way. If thoughtless development and illegal fishing continue at the rate they were pre-Ebola, the coastal fishing villages, their cultures and the beautiful beaches of Sierra Leone may very well vanish in the next 5-10 years.

TID:

Since this was taken out of the country, can you speak more about how you ended up working in this region and what was the draw for you?

SUSAN:

I made my first visit to Freetown in 2009 while working with an American doctor at a hospital in Freetown. At that time, the country was ranked at the very bottom of the World Health Organizations Human Development Index (HDI). Life expectancy then was 41, it’s currently 46. It had dropped to just 26 during the civil war (1991-2002)! The hospital had no running water and sporadic electricity. I was staying in a room above the hospital morgue. This was how I chose to get my feet wet in photojournalism.

I was self-taught and just a suburbanite mom, but I had the desire to do this since I was a kid. As you can imagine, my eyes were popping out of my head. There’s nothing anyone can say to you to prepare you for such an experience. I had such a visceral reaction—disgust, rage, and a sudden sense of purpose—because people were being screwed over by corruption. It was the best life decision I think I ever made. Maybe my next best decision was deciding to go again.

Salone—as locals fondly refer to it—wasn’t really a destination for anyone but aid workers, adventurous travelers, some business people, and of course, miners. The infrastructure was pretty dismal with roads, electric, water and sewer systems all in shambles. The war ended in 2002. In January 2014, the country was really starting to get back on its feet. Two five-star hotels had even opened in Freetown!

And then, Ebola hit.

I suppose the draw for me is to change the world’s perception of Salone. It’s such a gorgeous country with the most beautiful people. There are several corrupt ones that need to go, but there’s so much potential. They were just starting to buck the stigma of being the war-ravaged/blood diamond nation. Now, the challenge now is going to be to shake the disease stigma that will remain long after Ebola is gone. I want to be part of that.

TID:

How did you prepare for this moment?

SUSAN:

I spent a lot of time getting to know people. They trust me. I hang out with them, with and without the camera, and most importantly, I keep coming back.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

SUSAN:

Working in the dark was the biggest challenge. It’s really hard to see to focus and those two blue light bulbs weren’t helping matters any. Thank goodness the fisherman here turned on his flashlight, because without it, I couldn’t have made these shots.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

SUSAN:

A sense of humor and smile can get you far, and also doing a little homework. I spent a lot of time talking to the fishermen and meeting their families. These guys played soccer earlier in the week and were impressed that I had hiked up the hill to their game. So, I guess I earned points for being everywhere. I stay involved when I’m there.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment.

SUSAN:

I was sitting on a stump drinking a beer when the one fisherman turned on his flashlight. It was like someone turned on a painting. It was beautiful— the shocking white, blue and the black and white pattern on the game board. I asked one of the villagers to hold my beer (bad things usually happen when you say that!). It took a bit of cajoling, but they let me sit in with my camera.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

SUSAN:

Two marriage proposals, and, the fact I got a relatively sharp shot.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

SUSAN:

I’m happiest when I’m shooting and taking risks. To make images, you have to put yourself out there. I’ve just turned 50. I used to think getting older was going to be awful, but I’m enjoying myself and my work immensely. I seem to be getting a lot more flexible and open to new things the older I get. I’m not afraid of taking chances and making mistakes. I think that’s opposite of how we’re supposed to be. That’s a good thing, isn’t it?

TID:

What have you learned about others?

SUSAN:

People are pretty much the same wherever you go. They like to talk about themselves and I like to listen. I believe most people are good at heart.

TID:

What impact did this experience have emotionally on you?

SUSAN:

Over the years, I’ve fallen in love with Sierra Leone. My heart aches when my phone rings and it’s my friends from the village. Lately, it’s all been bad news. My friend lost his father, two siblings and his uncle to Ebola. He calls and cries. The new school I did a story on a few years ago is now being used as a quarantine area for the sick. Many have died in the village. The children have been out of school for most of last year.

I want very much to be there and tell the story of my village. If there were a news organization out there willing to cover my medevac and insurance as a freelancer, I’d be there now. The financial risk is just too great for many freelancers to go it alone. A friend of mine got stuck there when flights were drastically reduced. His company paid $20,000 to get him out. I’ll be back soon though. The story, for me, is what will be left behind once all of the journalists leave and the world forgets about Sierra Leone, again.

There’s a real sense of community there—a depth of connection that is hard to come by here in the States where we're so isolated in our offices, homes, and busy lives. As I said before, I love the country and the people. I hope that comes across in my work.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

SUSAN:

There’s a John Berryman quote I find motivating and perhaps others will, too. “We must travel in the direction of our fear.” To me, that’s where we discover ourselves.

:::BIO:::