Spotlight on Stuart Palley

Sep 2, 2016

TID:

This image, along with many of your others, are stunning. Can you tell us some of the backstory of the lead image?

STUART:

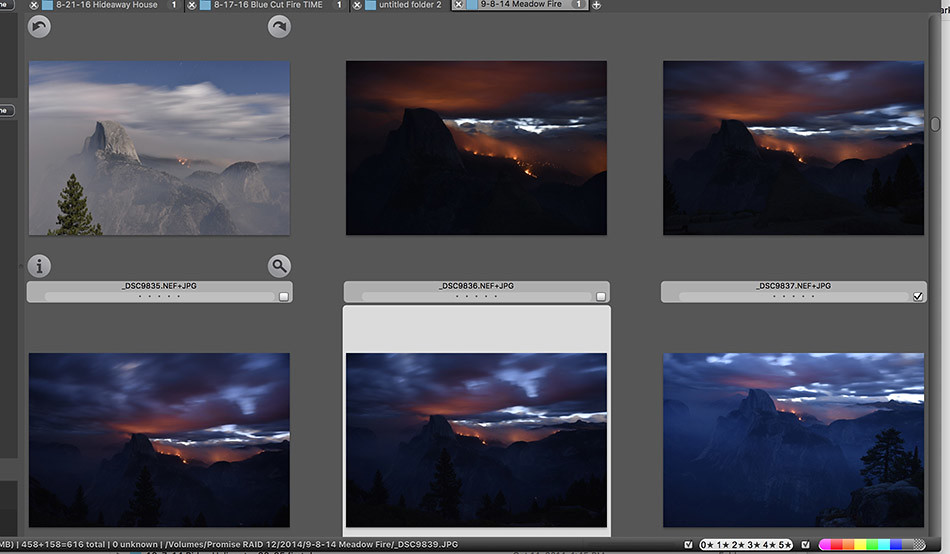

The image of the Meadow Fire behind Half Dome in Yosemite National Park almost didn’t happen. I was spending the day with family and driving back to downtown Los Angeles, where I lived at the time. I saw on Twitter, where I get a good deal of breaking wildfire news that a fire had started in Yosemite near Half Dome at a few hundred acres. They National Park Service was evacuating hikers by helicopter from the Half Dome trail and it was burning pretty well.

It was a Sunday afternoon and normally, I wouldn’t drive hours into the dark to photograph a fire that might die down overnight. There were forecasted thunderstorms that might extinguish the fire halfway through my 300-mile drive up to the Sierras. However, I looked at the Yosemite Conservancy webcam, and thought if I could get up to Glacier Point Viewpoint that night, I might have a shot of the fire with Half Dome in the foreground. For me, the frame was not technically difficult, and did not require hiking, smoky conditions, or extreme heat, but being in the right place at the right time to capture California’s extreme drought and amidst a national treasure was paramount. I strongly felt it would put an identifiable landmark in context with fires so that the public might resonate with it more.

For each wildfire I photograph and make long exposures of, I try and place the fire in the context of its environment. Is it burning in a Wildland Urban Interface area near subdivisions? I’ll show the houses in the frame. Or is it burning in the woods, where the expanse of the forest might be helpful to add dimension to the shot? Each wildfire has it’s own personality, it’s own behavior if you will. Some are similar in behavior due to weather conditions, fire history, etc, but each is always its own beast.

TID:

Tell us more about how you began this type of work. What drew you into it and why?

STUART:

Since I started photographing in high school I’ve been interested in natural events on mankind. I visited Thailand in 2005, 6 months after the terrible Tsunami that hit Southeast Asia, and ended up photographing some of the cleanup efforts and rebuilding of life in the Gulf of Thailand. During high school, I photographed the Salton Sea in Southern California, a manmade-sea that’s becoming a victim of drought itself and ecological issues. This ended up becoming my master’s project in graduate school. After moving to Texas for undergrad and Missouri for grad school, I found myself moving back to California in 2013 to a state entering the grips of a severe drought.

Between graduate years at Mizzou in 2012, I interned at the OC Register, and one day photographed a brush fire in the region. When I arrived at the fire (this was my first wildfire) a beautiful ranch home in the hills of Riverside county was on fire. Firefighters were trying to save what they could, family photos, a toolbox from the garage, a child’s Barbie car. I was struck by this contrast between man and nature, and how we fought it and reacted to it. The palm trees in the backyard smoldered as the firefighters did what they could.

So as I returned to California a year later, I became interested in documenting fires. Literally 4 days after moving back we had a huge fire in 2013, the Powerhouse Fire, that burned 30,000 acres north of LA County. I shot the fire all day, and eventually started to head home once it got dark. The idea struck me it might be fun to stop and make some frames of the fire at dusk as I drove out. The results intrigued me, and I ended up staying for another hour shooting as the stars became visible.

As the summer wore on in 2013 I focused on making pictures during the day, but tried to stay at night to shoot frames in the glow of the flames. I increasingly realized that A I enjoyed shooting the fires more at night, B less people were covering it that way, and C, was able to see an awesome force of nature up close and personal.

I’m inspired by the work of Vincent Van Gogh like his Starry Night and French café shots, where he uses the color palette produced by the night to illuminate the scene. Van Gogh is quoted as saying “I often think the night is more colorful than the day,” and I agree. Thomas Moran’s 19th century work in the American West also influenced me, showing man as small in the context of vast expanses of land.

Seeing a force of nature up close like fire is both humbling and mesmerizing at the same time. One is literally seeing the landscape change in front of their eyes.

TID:

What type of preparation did you do before heading out on shoots like this (this is not an easy subject to cover, and I was curious as to your thoughts of preparation).

STUART:

After photographing wildfire for 4 years I’ve learned that constant preparation is critical to successfully making images in the field. For gear organization this means keeping batteries charged as often as possible, with plenty of spares. Spare cameras, lenses, tires, goggles, you name it. Sensitive electronics are well, sensitive in extreme heat, dust, and ash. Have your stuff organized and know where everything is so you can move quickly and efficiently when donning safety gear and cameras in the field, and that way when things are hectic, moving fast, and your heart is pounding, you’re working off muscle memory and can focus on making pictures and staying alert and safe.

Conceptually, I read the regional fire weather forecasts every morning to get an idea of how likely a large wildfire might be. There are days when I know there will be a good chance of a fire, and I absolutely have to be ready to go at a moments notice. Other days I can hit the beach or live life. If there’s a Red Flag Warning for fire weather in a certain part of the mountains, coast, Sierras etc, I’ll take a quick look on Google Maps of the area, the roads in the region, topography, and nearest towns. If a fire starts I’ll look a little deeper to get an idea of logistics, where I might sleep or camp, and how many day I need to be gone for. In my free time I do daytrips to various areas in Southern California that have historically had large fires, so I can get a feel for the terrain, roads, and vantage points. For the forests close to me I have pre-scouted vantage points where there might be fires in the future, and it’s actually paid off in a situation or two to know where the good lookout spots are for the overall night scenic shots.

Onto specifics for camera and safety gear, there’s a lot of it. I’ll start with the camera tech and move onto fire specific Personal Protective Equipment, or PPE.

Camera Equipment:

My main camera bodies are a Nikon D5, 2 D810s, and a D4 for backup. I use the D5 for most day shots and low-light handheld shots, and switch to the D810s for the long exposures at night of fires. I use the D4 when it’s really smoky.

The lenses used most for fires are the Nikon 24-70, 70-200, 17-35, 14-24,200-400 VR, 58mm 1.4, 24mm 1.4, and lately the Sigma 20mm 1.4 lens too. If I’m hiking around I usually use just the 24-70, unless its at night when I carry the 24 1.4 and the 58 1.4. If it’s off a tripod for the night long exposures I’ll carry the 14-24 and 24-70.

I carry most of my gear in a Think Tank roller that stays in my car, and carry a lens or two in a pouch I attached to my fire pack.

For support I use a couple of beaten up old Gitzo carbon fiber tripods, a 3341LS and a 5 series as well for my 200-400 lens. The ballheads are Really Right Stuff BH-55s which hold just about anything rock solid and are almost indestructible. I also use a cable release for the long exposures.

Safety Gear:

I carry and wear the same PPE/safety gear as your standard wildland firefighter. Specifically that includes Nomex shirt and pants, helmet, 8-inch leather heat resistant wildfire boots, New Generation Fire Shelter, gloves, shroud, and goggles. I also have a specialized wildland fire pack that carries the fire shelter, water, gloves, power bars, first aid kit, and spare lens pouch. It weighs maybe 25 pounds total but it’s still about half or less of what actual wildland firefighters carry.

TID:

Once on site, how do you mentally work through scenes and importantly, how do you stay safe?

STUART:

The first consideration at a fire is safety and staying out of the way of firefighters. Once safety has been provided for and I can work out of a fire crews’ way, then I will start making pictures. I assess the weather conditions, terrain, what the fire is doing. Before taking a picture I try and go over these items in my mind to have up to date situational awareness should conditions change. I’m grateful for the fire training I have as it gives me the understanding of changes in fire behavior and weather to recognize.

The first thing I look for, during the day, are any moments that tell the story of the fire. Are people evacuating? Are firefighters struggling to save a home? Is a DC-10 jetliner about to drop 10,000 gallons of flame retardant on me? At night its more about vantage points and using the glow of the fire and the blue of the night to contrast and add color to these scenes that are often ash-colored and gray during the day. Are there viewpoints that show various elements of the fire in one frame? I move around a lot, hop scotching from location to location at night. I usually stay close to my vehicle and the road at night, both to move quickly and for safety should I have to move quickly. I’ll sometimes hike more during the day if I’m shadowing a fire crew.

TID:

Logistically speaking, how do you move around from situation to situation? How do you know when it’s time to leave?

STUART:

When moving around at a fire I’ll either walk or drive my car as the terrain and conditions permit. Sometimes you can ride with a public information officer or even a captain, etc., with the incident commander’s permission. It all depends on where it is. Most of the time its in my 2007 Ford Expedition EL with 175,000 miles on it. It’s a reliable truck that holds all my gear that has 4 wheel drive. It has radios, food, water, etc and is my mobile office/fire base.

I will move to another viewpoint or situation once I feel I’ve made enough frames that properly convey the message I’m trying to share, or the fire behavior changes forcing me to move. Additionally, if the fire really picks up at another spot, I’ll sometimes head to it.

Safety wise, I’ve never felt in very serious danger, but there are plenty of situations where the fire behavior changes and I have to move in order to stay safe. That is, the training I have allows me to recognize and manage potentially hazardous situations before they occur. Of course, wildfires are natural and sometimes extreme and unpredictable, so there is always risk. When things are getting intense I’ve learned what risk I’m willing to take and when I’ll walk away. No photo is worth a burn injury, death, smoke inhalation, etc.

TID:

I’m always interested in how photographers problem solve. What problems did you encounter during shooting fires, and how did you overcome/work through them?

STUART:

The biggest challenge in photographing wildfires is getting to them in time, safely navigating them, and knowing when a fire is worth “rolling” to or not. I’ve photographed enough roaring fires and duds alike o have a decent idea of when pictures will be present. We’re also in the 5th year of a severe drought, so unfortunately everything is burning heavily right now.

To better my response rate to fires, I keep all my gear loaded in the Ford with water snacks, etc. The radios I use are scanners to listen to fire traffic, so as I drive to a fire, I get an idea of where to go and of what’s going on. I keep a go-bag of sandwiches and snacks in my fridge so I can change into my fire gear and head out the door when I’m working at home. If I’m on a shoot or assignment, and the fire danger is high, I’ll load a cooler for the day just in case there is a fire.

So working through the logistics concern, was to think like a boy scout and become very prepared for possible scenarios, so when I do decided to photograph a fire, there is minimal preparation and I can head into the car and passively listen to the radio as I drive. It allows me to hit the ground running with a decent understanding of what’s going on and start making pictures.

The other persistent problem is wear and tear on gear. The smoke and ash and dust is not friendly to even professionally weather sealed cameras, and I tend to bang lenses into trees and drop cameras in ash pits. So I try to carry less gear with me and to be more careful with it when 100 other things are going through my mind. No point covering a fire if I break all my gear and then have to spend the wildfire photography budget paying for it.

TID:

What has surprised you about covering fires?

STUART:

The biggest surprise, since I started in 2013, was how current of an issue the drought and wildfire has become in California. I did research at the onset of the project and realized that it could potentially become a “big deal,” but I didn’t think we would be here in 2016, still in severe drought, with a bum El Nino in winter 2015 and no relief on the horizon. I’m actually scared at this point, because the western slope of the Sierras are basically going through a desertification process. Seeing how recent fires in August burned in Southern California, I am also surprised to see if firsthand, even though the weather forecasts and data correlate that kind of fire behavior.

TID:

Now, onto the main image. Can you walk us through the day and moments leading up to it? Additionally, can you talk about what you were thinking processing while making the image?

STUART:

July and August 2014 were busy months photographing wildfires, so by September I was starting to become fatigued with coverage. I had spent the weekend with family and was driving home Sunday afternoon when the fire happened. I detail the lead up in the first question, so I’ll move to where I got up to Glacier Point and the fire looked out.

After getting there and not seeing much, I made a few frames. I then found myself falling asleep for a few hours an waking up at about 4:30 am to try and shoot the sunrise. The wind had picked up a little bit, causing the fire to pick up and glow a bit more. What made the shot, for me, was the first rays of light for that minute or two at the prime time of blue hour, the lightness of the sky contrasted the glow of the fire almost perfectly. I made about 5 frames, then the sky was too bright.

Again, I decided to drive up because I realized that a fire behind Half Dome could be an image that connects wildfire and the drought with a national treasure that many Americans and the world might recognize.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself after covering all of these fires?

STUART:

Push hard, don’t give up, you have more energy and strength than you know. But also know when to rest, pace yourself, and say no to preserve to your top energy and focus for when you really need to double down on making pictures.

No shot is worth risking your safety, or that of others.

Have redundancy with your equipment, extra camera bodies, lenses, tripods, and lots and lots of batteries. Have inverters, at least 2, so you have ways to charge your gear on the road, and then some more batteries. Invest in a LTE hotspot with prepaid data to file from the field fast, so you don’t drive 2 hours roundtrip from a fire to find wifi in a tiny town. And have it all INSURED so if your car burns up, your business isn’t ruined. But plan on paying for all the minor gear issues out of pocket.

PS I also learned where all the good places to eat are in the Central Valley on the 99 and 5, and which motels to avoid since they’re infested with bedbugs.

TID:

What have you learned about others from doing this type of work?

STUART:

I’ve learned that firefighters are a special breed, - selfless, hard working, and willing to lay down their life in an instant to help a stranger in need. I see it time and time again at fires, men and women from all the departments rushing into towns and forests to save homes and help evacuate people when the proverbial !@#$ is hitting the fan. They risk long term lung issues, PTSD, long hours, and sometimes low pay to do a tough job, working in extreme heat in hot Nomex and heavy boots. They hike up and down mountains and sleep in the dirt, but for the most part, they love it. Their outlook on life, and kindness on showing me the ropes on how to be safe I will never forget. I’m grateful to count some of them as friends.

For those affected by fires, the kindness and grace by which humans can act with when faced with losing their home, hopes and dreams. Seeing a community come together to provide each other with food and shelter during a large wildfire, rescuing each others’ pets, providing a shoulder to cry on. Handing me bottles of Gatorade even though I’m just a photographer, bringing cookies to firefighters in fire camp. Through wildfires I've seen tremendous destruction of both forests and homes, but I’ve seen how powerful the human spirit can be. Oddly enough natural disasters bring out the best in people, and almost always, they band together and rise to the occasion.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice would you have for someone wanting to do this?

STUART:

First and foremost, invest in the proper safety gear and training to photograph wildfires safely. The majority of media outlets from TV stations to newspapers DO NOT provide their staff with even the most basic safety gear, not to mention fire shelters. Demand that your editors provide you with gear to do jour job safely, or turn down the assignment.

Second, get training, which local fire departments often do for free each spring. Both LA County Fire and Cal Fire offer annual media courses for how to safely work on a fireline that take a day or two, and can be extremely helpful for those new to covering wildfire.

Third, make sure you train physically by running, hiking, lifting weights, etc. Photographing fires is a surprisingly physical in the heat and carrying around gear, and conditioning your body can make it less stressful and fatiguing when running around the fireground.

Last, insure your gear and use maybe older used equipment you wouldn’t miss having totally destroyed. Don’t give away your work for free.

:::BIO::

(Photo Credit: Captain Jason Hobby)

Stuart Palley is an award-winning Southern California based photographer specializing in environmental, editorial, commercial, travel, documentary, motion/video, and fine art subject matter. Born and raised in Southern California, Stuart has photographed for National Geographic Magazine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and many other publications. His work has appeared TIME Magazine, WIRED, New York Magazine, and The Washington Post as well.

In 2016 Stuart received an Honorable Mention in the Environmental Vision category of the prestigious Pictures of the Year International competition, and has been recognized years past. His recent work on wildfires, Terra Flamma: Wildfires at Night, has been featured in TIME Magazine’s Light Box, Time Magazine’s Photos of the Week, Time's Top 100 Photo of the Year The Washington Post, New York Magazine, The Today Show, The Wall Street Journal, WIRED, and newspapers and magazines worldwide. The work was also featured on Instagram's blog and on Instragram's account. Stuart originally funded the project by running a successful Kickstarter campaign where he raised 260% percent of his original goal. He was able to envision, fund, execute, and complete the project totally independent of any publications or institutional funding.

Stuart received his BBA and BA from Southern Methodist University and studied finance and history and minored in Photography and Human Rights. He holds a Master’s in Photojournalism from the University of Missouri. Stuart is available locally and worldwide for select commissions and assignments. Please use the contact page to get in touch for his availability and rates. See his gallery for fine art prints of his favorite work.

You can see more of his work here: