Spotlight On Sam Dean

Apr 7, 2012

TID:

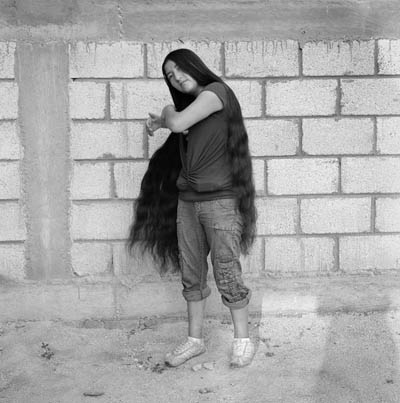

Sam, this is a really powerful picture. Can you let us know some of the backstory?

SAM:

This moment was the conclusion of sorts of a very tragic story for the readers of The Roanoke Times: A little over a year (Oct. 2009) before this moment, Morgan Harrington left a Metallica concert at the University of Virginia’s John Paul Jones arena. She was never seen again.

Her parents, Dan and Gill Harrington, the subjects of the photograph, spent several agonizing months pleading via every viable means for the return of their daughter. Sadly, a farmer found her remains in a field in January of 2010. Over the course of that year, the Harringtons became very comfortable with the media, so it was no surprise when area outlets were alerted in January 2011 that there was a significant development in the case.

Of course we were all hoping they had a break in the case. Perhaps even a suspect. The focus of the day’s events was to be a visit to the site where Harrington’s remains were found. After spending the day following investigators to various sites linked to the investigation, at long last, a train of television news vans and frumpy newspaper reporter vehicles wound its way down a narrow road south of Charlottesville, Virginia and circled through pastures before coming to a stop near the top of a hill.

As the small army of journalists assembled their gear, the fragile looking Harringtons waited dutifully beside their car. And then we were off. Photographers trotted beside them or ran to get a better angle up ahead.

As we descended the hill, the strength Gil Harrington had composed finally melted and she began to wail as we drew closer to the site we all now knew was where her daughter’s body was found.

TID:

What was going through your mind when you began the shoot?

SAM:

Sadness.

I was anticipating this moment all day, trying to prepare emotionally and practically for it. I tried having conversations with some of the other photographers about a less intrusive way of photographing the scene I was sure was coming. “Let’s agree to give them their space at the scene,” I said, or something to that effect. My thought was if we were back with longer lenses, we could still make powerful images without turning their sacred moment into a circus. I’ve become hyper aware of the “how” a picture is taken being as important as the “why.”

That didn’t happen.

I hadn’t been intentionally following this story; it was just the assignment I drew that morning. That’s how I work most of the time. I’m a community photojournalist, so it’s my duty to be the eyes for our readers. This day I was there to help our community mourn with the Harringtons.

There’s a bit of a battle going on in my head in a moment like this: I take seriously my duty as our community’s visual historian, but I must try to do no harm. It’s a necessary tension, much like the idea of grace and good works. I’m not sure if the line is ever very clear.

TID:

I always wonder how people's body language affects things. Can you speak

to how you carried yourself and interacted with others?

SAM:

I try to balance being quiet and distant (spatially) with honest interaction when it seems right. To be too distant is contrived. People aren’t simple: they just want you to be honest. On the other hand sticking a 24mm in a subject’s face in the middle of a painful moment is something that one shouldn’t take lightly. Often an equally strong image can be made from a distance, which is less intrusive. Damon Winter is really good at using longer lenses intimately and I think most would agree that he’s pretty good at what he does.

After going through a layering phase in photography when I was younger, I really came to appreciate the honesty and simplicity of medium and longer lens images. Steve McCurry’s portraits come to mind. Young photographers should occasionally put away the wide lenses. Try shooting with nothing wider that a 50mm. Think of it almost like a sports action photo: it really is about the moment. Don’t get me wrong: I love wide, layered images, but I think we need both approaches in the tool bag, both so we can be better storytellers and human beings.

TID:

Can you also talk about how you speak to people in sensitive situations?

SAM:

Again, honesty is key here. I never want a subject, especially in this situation, to feel as though I’m manipulating the situation. I’ve also had pain in my life, so if I speak to them, which I did, I try to be intentional and honest. People respect that. They need it. Journalists should be aware that we can easily manipulate a situation. In fact, we may not be able to escape the fact that we always manipulate, but more on that later.

As we returned to the cars, I remember taking Gil Harrington’s hands and expressing my sorrow for her loss. I’m a crier, so I’m sure I got a little misty, too.

TID:

Now, on to the moment. Please describe what happened.

SAM:

As with all moments, anticipation in key. Once I realized that it was going to be a media frenzy, I had little choice but to join the fray. Cameras up and microphones out, we stood shoulder to shoulder as the Virginia State Police investigator described how Harrington’s remains were located in the dry grass in front of us. He then motioned for the Harringtons to come forward. Gil Harrington, who was inconsolable, moved toward and started to kneel at the spot directly in front of us where her daughter’s body was found. Sadly, a young television reporter to my left, who wished to retrieve a wireless mic from the state police investigator, started walking through this spot at the same time.

I imagine that to a mother who is viewing this place for the first time, this must be sacred ground, so with that thought in mind, as well as a fair bit of annoyance that this reporter was about to ruin the moment, I grabbed the back of her pink coat and pulled her out of the scene with my left hand as I knelt to photograph with my right. Luckily, Gil Harrington was so focused on the scene that it didn’t cause a disturbance. Moments later Dan Harrington joined her and I took the photo.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself in the process of making of this image?

SAM:

I’m not sure if I learned anything new so much as I had reinforced ideas I have about balancing being human with journalism.

TID:

What surprised you about the assignment?

SAM:

That I was able to make the image I envisioned. Trying to script things too much is a dangerous game, but the best photographers always try to anticipate a moment. Many times it works out. Many times it doesn’t, or a better moment presents itself. If I try to script a story too much, in the end I’m trying to photograph the story the way I’ve preconceived it. That’s not journalism. You’ve got to be loose and follow the thread where it takes you, while always being aware of where it looks like it’s going so you can be in position a shutter click in front of the moment.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers in similar situations?

SAM:

Always put yourself in your subject’s shoes and then make truthful images. Start by realizing that it’s their story you’re taking and telling. They may give it to you, but you’re still taking something that for them is sacred; you’ll move on to the next story, but they have to live it. We try to make ourselves feel better by saying we “make” images. Really, this is rubbish: We take them. So it’s a duty, then, to honestly retell their story and to manipulate as little as possible a subject’s emotions to get it.

While covering the Virginia Tech shootings in 2007, I saw the fallout from callus journalists descending on a small town, many of them just trying to fill out a portfolio, it seemed. Many of the images made during the days and weeks following the shootings were style-driven and empty, and the methods some photographers used only furthered the pain of the grieving community.

Too many young photographers focus on style to the point that their images are vacuous because the medium has become the message. They have either forgotten or never learned that it’s always about honestly telling someone’s story. How we do what we do matters as much as the end result.

***

BIO

Sam Dean is a husband, father, photographer, journalist and writer living in Vinton, Virginia, with his wife Niki, 3-year-old Colter, a white german shepherd and two cats.

Sam proudly hails from Lubbock, Texas. After a childhood spent trotting the globe with his missionary parents, a love for rock climbing and skiing lead him to the University of Montana where he received a degree in journalism in 1999. He has been a staff photographer at the Roanoke Times since 2000 and has covered many compelling stories, including Elian Gonzalez, conflict in Afghanistan and the tragic shootings at Virginia Tech.

You can view more of his work here: www.samdeanphotography.com

Next week we'll take a look at this image by Michelle Frankfurter:

If you have any suggestions or if you want to interview someone for the blog, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting.