Spotlight On Nick Oza

Oct 15, 2011

TID:

Nick, thanks for taking the time to speak with us.

This is such a powerful image. Can you talk a little

about the background of the picture?

NICK:

Back in 2006, then-Arizona Republic reporter Judi Villa,

and I were shadowing a gang task force unit with Phoenix

Police Department. The story was focusing on how Phoenix

gangs were seeing an influx of members from Los Angeles.

We were working in neighborhoods just south of downtown

Phoenix when we heard from the police radio that shots had

been fired in a nearby predominately Hispanic neighborhood.

We were just a few blocks away from the scene. It was

pandemonium. A man had been shot. He was lying in

the middle of the road, dying of multiple gunshot wounds.

His friends and family were hunched over him, begging

him to not succumb to his wounds.

I asked the detective if I could approach the crime scene.

He said he would “take some heat,” but allowed me to take

photos because it was such an important story. Then the

detective told me that the man who had been shot was the

same man who just 10 minutes earlier had refused

to talk to me for our story.

I approached the scene. The man’s mother screamed, "Oh my

God, please don't leave me!" to her son, as she prayed over his

body. But it was too late - he was already gone.

TID:

This image is part of a larger story, can you tell us

what was the origin of the story (how it was pitched

and began), and how long you worked on it?

NICK:

The Republic’s Director of Photography, Mike Meister, put

full faith in me as the new kid on the block. It is very important

that your photo editors know your strength, instead of just

seeing who is available during the shift (I have always been one

of the "street guys," so this assignment was a good fit.}

At the time, I was just three months on the job, and didn’t know

the city’s neighborhoods well. Villa, who for years had reported

and written about crime in the Valley, pitched the story about a

resurgence of street gangs moving west from California to Phoenix.

Officials were reporting that the gangs were more violent and more

organized than before. So, we went with police for an 11-hour ride-along

to document the growing problem.

Along the way, we made several stops looking for

gang associates, and documented as the police

responded to crimes related to the gangs – including

a carjacking and a drug search in a suspected

gang banger's car. Villa and I worked on the story for

a week. Our work resulted in a front page

Sunday story and an online slideshow.

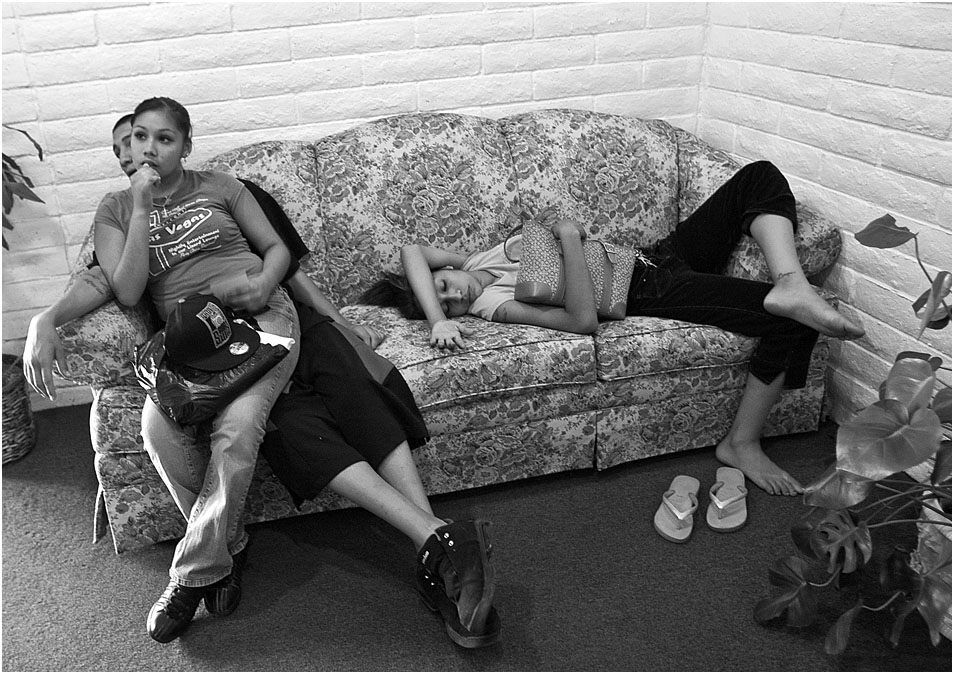

While reporting the story, I kept in touch with Grace

Villavicencio, the mother of Andrew Vargas, who had died.

She allowed me to document her as she visited her son’s

body at the morgue, the funeral home, at the cemetery

where he was buried, and later, she invited me to her home.

TID:

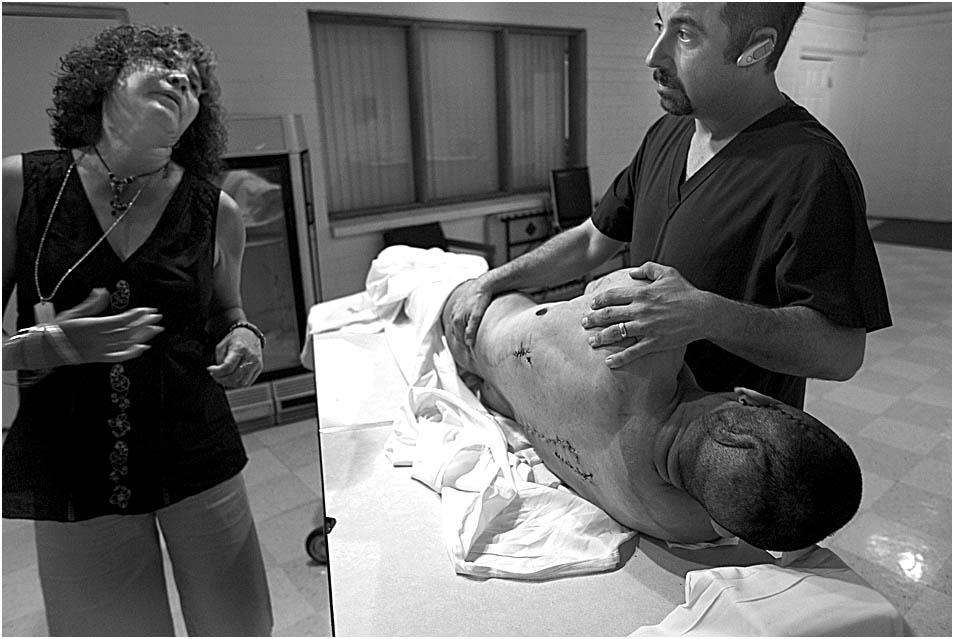

This picture below is very disturbing. Can you tell us what

is going on here, and how you managed to get the picture?

NICK:

His mom called me on my cell phone and asked me if I wanted to join

her to see her son for the first time at the funeral home. It was the first time

I became emotional and I said, "Are you sure?" When I went to the morgue

the guys were yelling at me to get out but the mom said, "He's with me."

As soon as we got in the room I stayed behind. I was observing the scene,

and I started hearing a brother of the victim crying hard. This image was

when his mother was explaining what happened. Vargas said,

to her son Kiki, "Look what happen to your brother. They were trying to kill

you and now your brother is laying for you." It was such a surreal, dark, scene.

I hid my face behind the camera so they couldn't see my emotion.

TID:

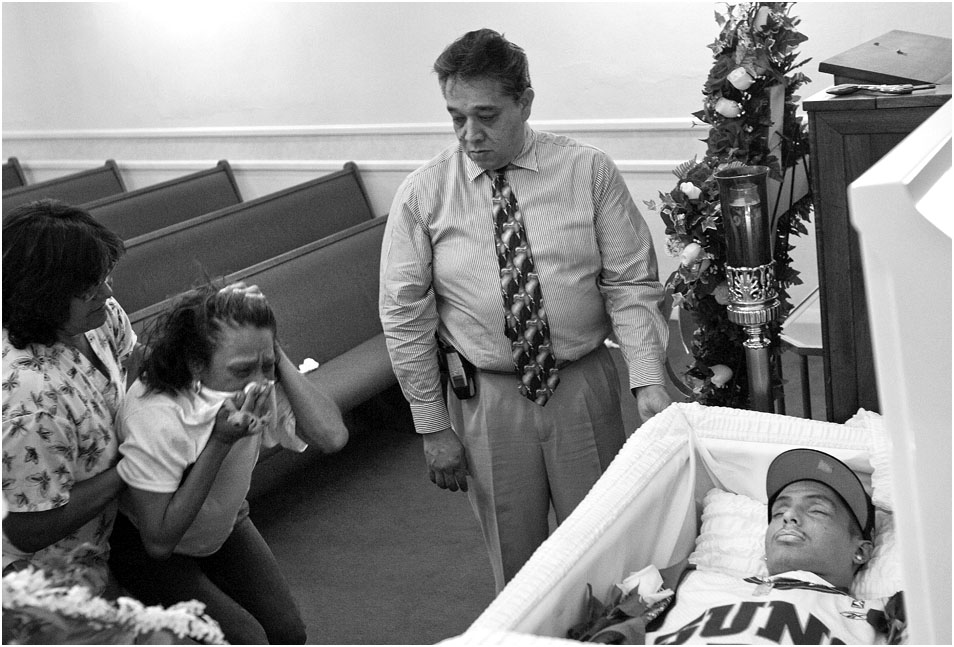

One of the things I admired most about your coverage of this,

was how much you stuck with it. You eventually covered the

funeral of the person who was shot. How did you gain access?

NICK:

It was simple, they actually called me to let me know about

the wake. I had earned their trust enough for them to call me.

TID:

What was your approach to this story?

NICK:

I wanted to tell the story of a mother’s grief from her

point of view. Oftentimes, gang related stories are

told from the point of view of law enforcement, and

too often, the emotion behind the story – the gut-

wrenching grief of a family – is untold.

I set out to tell that story. I immediately got to work

to try to get to know the mother. Two days after the

shooting, I returned to the street where the man died.

I wanted to see where he came from, where he lived,

who his family was. Neighbors directed me to his mom’s

house. I knocked on the door, and made my pitch: I

wanted to illustrate how Phoenix’s gang problems

affected her family, and tell the story through their eyes.

She said she remembered me as being respectful at the

crime scene. She invited me into her home, showed me

her son’s room, and talked with me about her son, and

how he became a gang member. Since she was willing

to tell her story, others were, too. That credibility allowed

me to “work the streets” and find other gang members

who talked with us for the story.

TID:

Ok, now onto the image itself. Tell us what led up to the

image, and what was going on in the moment.

NICK:

The crime scene was very surreal.

Over the years, I have covered emotional scenes. I’ve seen

people die in combat. I’ve photographed many murder scenes.

But this one was different knowing that I had just spoken to

the victim a few minutes earlier. (Later I learned from police

that the man was not even the intended target. The gang

members meant to shoot his brother).

On the scene, I heard two young men swearing and asking

the victim to not give up. The mom was crouched over her

son, crying. And the cops were trying to gather information

from witnesses and the man’s sisters.

It was a very sad scene. What shook me the most was the

way the mother was sobbing over the loss of her child. I’ll

never forget it. She was cradling her son’s upper body, rocking

him back and forth. As a father to a young child, I cannot

imagine losing my child in an instant – and so traumatically.

The memories of that day will haunt me forever.

TID:

Were there any points of conflict or struggle during the

making of this picture, and how did you handle it?

NICK:

The biggest challenge in getting this photo was getting the

police to allow me to take pictures of the body. Because of the

sensitive nature of the scene, I had to stress to the

detective that the public had a right to know what was

happening. While sad, the man’s death illustrated the point

of the story: that increased gang activity was leading to more

crime and violence in certain areas of the city.

At first, the detective would not allow me to take photos. After

some back-and-forth on the issue, the detective finally allowed

to me to shoot photos, saying, “I’ll take the heat.” And he later did.

The detective also asked that I take only tasteful photos. I only

shot half a dozen frames - the least amount of photos I’ve ever

shot on any assignment.

Also some of the gang members and their friends were not happy

that I was there taking photos. But as time wore on, they grew

tolerant of me and didn’t get in my way. The lesson I learned there

is that patience and respect will overcome almost any story.

TID:

What was the reaction after the image was published?

NICK:

The images of that scene were very powerful. Response came

in from within and outside of the newspaper, saying that the

photos captured the mother’s grief. I heard from the family,

police, neighborhood activists, and my peers.

TID:

I'm sure this was a tough moment, and story, to work on.

What lessons did you learn from this experience?

NICK:

This story really instilled my belief that if you are honest,

persistent and respectful, you can work your way into any story.

When working on such sensitive stories, you often have only your

gut to rely on – those feelings that tell you to either keep pushing,

or stop pushing.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers to

get access to such moments, and also how to handle it

once you get access?

NICK:

I love challenges and I am not afraid to fail. My success is based

on all of the failures I’ve racked up over the years. My best advice

to photographers is to allow yourself to fail. Allow yourself to push

boundaries. Allow yourself to follow your gut feelings. Street

photographers must work fast on their feet and make snap

decisions that can either make or break access to a photo.

Oftentimes, photographers get stuck in the mindset that they

must quickly find photos and move on to the next assignment.

But I work on the philosophy that photography is a craft – a

means of exploration. Just work it and success will come.

As philosopher Muktananda has taught: if you are the master

of dancers, all of the dancers will follow you. If you are the master

of art, all artists will follow. But if you understand yourself,

everything will come to you.

TID:

You said, "I work on the philosophy that photography is a

craft - a means of exploration." Can you please elaborate?

NICK:

We as a photographer are too often driven by the narcissistic values

stemming from competition. Instead of focusing on this, I think we need

to explore and understand life issues more, as well as put yourself on

the other side of camera (imaging yourself in the shoes of others).

+++++

http://www.nickoza.com/

http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/2010/08/the-images-of-sb-1070.html

http://www.azcentral.com/community/surprise/articles/2010/04/07/20100407-parkinson-brain-stimulation.html

+++++

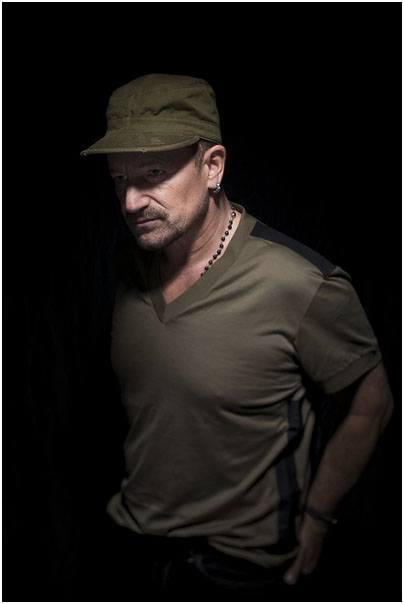

Next week we'll take a peek into celebrity portraiture with

this image of U2's Bono by Jay Clendenin of the Los Angeles Times.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

[email protected]

[email protected]

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/