Spotlight on Mitch Dobrowner

Aug 28, 2016

EDITOR'S NOTE: This interview was conducted by Devin Greaney (thanks, Devin!). If you're interested in doing a gust interview, please contact Ross Taylor: [email protected].

TID:

Describe what photographing the weather means to you and how you are drawn to it.

MITCH:

My first love has always been landscape photography. I have always loved just sitting out in nature, specifically in the American Southwest, looking out over the desert landscape, hearing the wind blow and watching the light as it changes. I love studying the light and see photography as an exercise in painting with light and shadows. In inclement weather, light and shadows are always changing. Then there are the unexpected things that Mother Nature throws at you, especially when a storm is approaching. It’s always a surreal experience for me. All I'm trying to do in my pictures is capture what I see and how I feel at those moments.

Photography is also my way to communicate how I feel without words. When I’m out photographing, things seem simple again. Time slows down and the world around me gets quiet - even when photographing storms. It’s then that I’m able to focus in a manner that allows me to connect with my imagination. Those moments are how I’ve learned to still my soul; it’s my happy place. It’s about the only time where I’m alone and can hear my heart beat again. I see myself on a mission now to make up for years of lost time by creating images that help evoke how I see our world.

TID:

Tons of severe weather images show up every storm season, none of them are even close to what I see here. It seems every detail from the scud clouds, to the "barber pole" updraft from the ground to the stratosphere shows in incredible detail. What helps you bring out the subtleties of the storm?

MITCH:

It's hard for me to explain how I feel standing in front of these amazing phenomenons of nature, so all I attempt to do is capture what's in front of me and how I'm feeling about it. Technically, having my b&w prints be my final product has been instrumental in my approach to visualization. As I love breaking rules, I adapt my cameras to capture the light as I see it.... and use an adaption of Ansel Adam's zone system as my own digital zone system.

This also allows me to use colored filters (R,G,B) on my lenses in the same manner that I used them when I shot black & white film. As I came from the world of b&w film, and used a 4x5" and 8x10" cameras as my primary tools, that and the science behind silver printing, the use of cold light printers, etc were all part of my foundation. I think those aspects and my study of sensitometry as a teen has helped me adapt a digital workflow that allows me to me happy with my prints (my final product) today.

TID:

There is an interest now more than ever in storm chasing from scientists, to the media to someone with a smart phone and a car. Describe some of the things that may surprise us about chasing storms.

MITCH:

When I first started photographing storms I thought of it as only an experiment, I had no idea what I was getting into. Today, to me storms are like living breathing beings. They are born when the conditions are right... they gain strength as they grow and mature. In the beginning you don’t know exactly what is going to happen. The storms can become violent and sometimes unpredictable; they can either quickly die or begin to take form and evolve.

Eventually, as they grow they’re like teenagers and they begin yo take on a life and an individual personality of their own. As they grow, they fight against their environment to stay alive. Some die quickly, others last for hours, change form as they age and eventually they lose their strength and die. The storms take on so many different aspects, faces and personalities. Photographing them is an experience unlike any other and an honor for me to witness.

TID:

Regarding the lead image, what was the scene was like and what was going through your mind when creating the image.

MITCH:

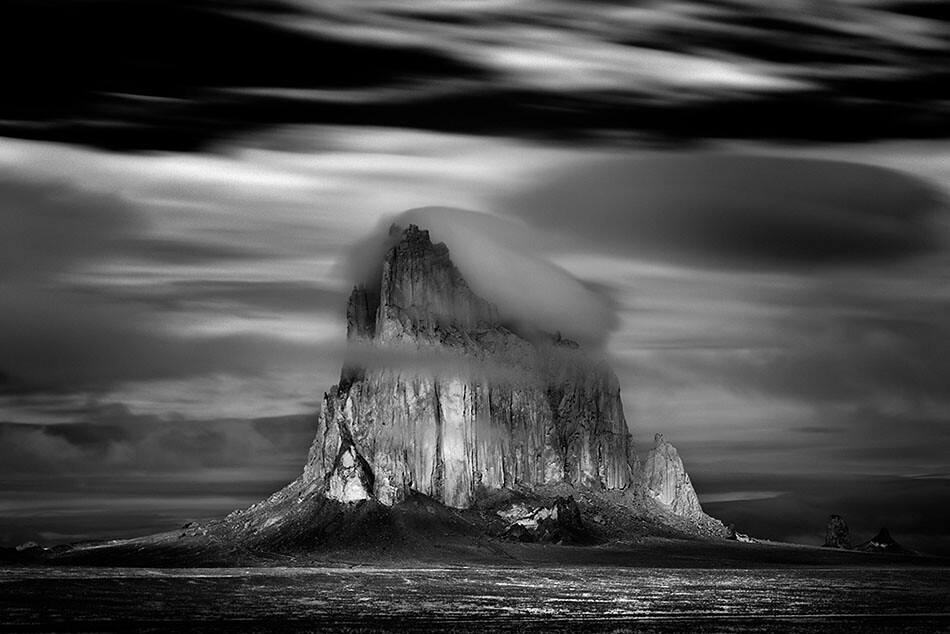

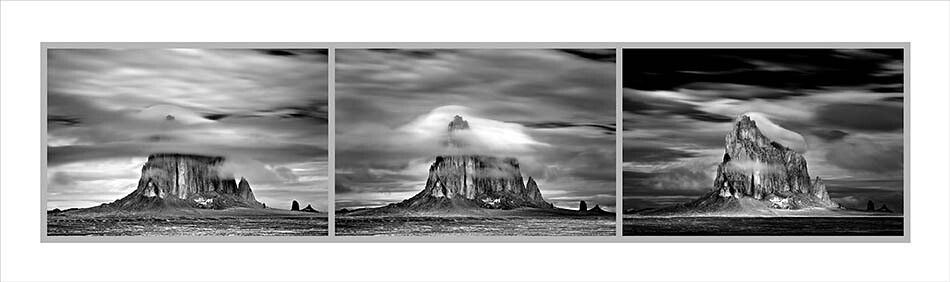

Probably my time at Shiprock, New Mexico, though there were others that came in at a close second, like the Valentine Nebraska storm. But Shiprock was very special to me. I had seen images of Shiprock before, but never the image I had in my mind. Though I hadn’t seen the formation in person, Shiprock touched something deep inside me. I think it was because I knew that it is the spiritual center of the Navajo Nation, or maybe it was because it is the remnant of an ancient volcano. But this combination of history and geology ignited something inside me. So I traveled to the Four Corners area of New Mexico with my family to photograph it.

When I arrived in Farmington, New Mexico, I was totally overwhelmed by my first distant sighting of this otherworldly formation. Over the next ten days, I woke up at ungodly hours to drive long distances in order to arrive at first light, and then left after sundown each day in order to catch the last light. I had to drive in the rain, over rocks, mud, snow, and sand. As we arrived in late December, storms were rolling in daily. Those weather conditions made for moody, atmospheric photographs, it also gave me frost bitten fingers and toes those first few days. I spent the first eight days driving, scouting, and sitting quietly in the area that surrounds Shiprock. It also seemed like the more time I spent in the area, the more I knew that I would need to be patient despite the cold.

On the morning of the eighth day, I woke up at 4:30 a.m. and got into my truck in the freezing rain and snow — with a warm cup of coffee. From Farmington, the drive to Shiprock was 50 miles one way. It was snowing, raining, dark, and freezing. The thermometer on my truck read between two and twelve degrees Fahrenheit above zero. For a few minutes I remember thinking I was nuts. As this was the fifth time in eight days that I was making this trip. My mind kept saying, “Why are you going out again when you could have stayed with your family in a warm bed? You’re an idiot. You’re not going to get anything.” But I felt driven, as I wanted to capture the image I had driven eight-hundred miles from California to get.

When I finally arrived at Shiprock that morning, it was about 5:45 a.m. The sun was just coming up and the Shiprock was behind a wall of clouds. A storm had just rolled in. When I finally stopped and stepped out with my camera and tripod, I sank ankle deep into cold mud. But when I looked up I knew that what was about to happen in front of me was the thing I had come all this way for. For the next three hours I sat in front of Shiprock, not a soul around, it felt like we had a conversation. My hope is that this image helps communicate what I saw and the humility I felt while photographing this amazing structure.

TID:

Any scary moments out there? What are some of the more important safety rules?

MITCH:

Na, I don't get scared. I don't mean to sound macho or touch.... I just don't get scared. The experience of standing in front of one of these amazing structures is just so amazing to me. Besides, my friend and chaser master Roger Hill always has an escape route. We never get ourselves in a super dangerous position, though we have what he calls close encounters where we get right under something, like a rotating cloud. It’s pretty safe though. One of the only rules is once we are "on the chase... is sip your water, eat light.... as we don't stop for anything... and I mean ANYTHING. But to be honest the only time I have ever scared is while standing out in the field and seeing a wild mouse. Wild mice scare the hell out of me!!

TID:

As you know storm chasers were killed and injured in the 2013 El Reno, Oklahoma twister. Since then have the authorities pushed back as a reaction to the storm chasers along the highways?

MITCH:

No, but they should. In fact when chasing/photographing storms what ends up being more dangerous then the storms is the traffic and the people. Sometimes there is a lack of judgement and/or respect for Mother Nature, and what she's capable of. People just need to pay better attention to what's happening in front of them.

TID:

With all the detail you have captured, has anyone from the meteorological community mentioned if your photos haven given new insights as to the structure of storms?

MITCH:

I don't think with all the research and science that has gone into meteorology over the past 10 years my work has given science any new insights. Though, I have received feedback from the National Weather Center in Norman, Oklahoma and their appreciation for the imagery; as for them the work (sometimes) can bridge the gap between science and art.... between all the research they perform and the beauty of the storm systems they study. In fact NOAA recently purchased my "Tornado Triptych" for the from lobby of the National Weather Center. I was totally honored by that as them doing that meant a lot to me.

TID:

What has photographing the weather taught you about yourself?

MITCH:

That we are small. That the Earth is beautiful, ever changing and evolving. That the land we think we own, we are only borrowing for the tiny period of time. That we are here; so respect it. But as a whole photography has allowed me to leave something behind for my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I don’t even know the names of my great-great-grandfathers—but they lived, just like we do. They probably lived very hard lives, and we wouldn’t be here without them. At the very least, I can leave my great-grandchildren a visual record of what this beautiful planet once looked like. When I eventually leave the Earth.... photography has given me an avenue to leave behind, through my eyes, my experience here.

TID:

What advice would you give photographers who may have some interest in storm chasing?

MITCH:

Do your research and have integrity and respect for Mother Earth. I know that sounds drab, but I don't see enough of that out on the field while chasing. My only other piece of "photographic" advice is: no matter what anyone says you should always follow your gut instincts. Don’t care what people think or how they feel about your work. Do what you want to do as it’s YOUR art. Even if it means breaking away from what everyone else is doing. Don’t follow advice, just do it! That’s all I ever do. Breaking from the pack is a good thing.

:::BIO:::

Growing up on Long Island (Bethpage), NY – I felt lost in my late teens. Worried about my future direction in life, my father gave me an old Argus rangefinder to fool around with. Little did he realize what an important gesture that would turn out to be for me. Dobrowner grew up in Long Island and was given an Argus rangefinder by his father to take photographs, and his inspiration drew from the images of Minor White and Ansel Adams.

He left home at 21 to see the American Southwest and in California met his future wife, and together had 3 children. They created a design studio together, and the tasks of running a business and raising a family took a priority to Photography. During that time he stopped taking pictures. Years later, in early 2005, inspired by his wife, children and friends - he again picked up my cameras. Today he sees himself on a passionate mission to make up for years of lost time - creating images that help evoke how he see our wonderful planet.

Dobrowner feels he owes much to the great photographers of the past, especially Ansel Adams, for their dedication to the craft and for inspiring him in my late teens. Though he’s never met them, their inspiration helped him determine the course his life would take. He lives with his wife Wendy, their son Joshua, dog Jet and their bratty cat Jax in Studio City California.

In 2013 he published the book STORMS. You can see more of his work here:

+++

Interviewer Devin Greaney is a Memphis-based freelance writer and photographer. He wants to see a tornado - but one that's out in a field that does no damage or hurts anyone!