Spotlight On Michelle Frankfurter

Apr 13, 2012

TID:

Michelle, thanks for your time. Can you tell us about this beautiful image's context and background?

MICHELLE:

I took the photo on my first trip to southern Mexico, as part of my ongoing project, Destino, about the journey by rail of undocumented Central American migrants. I began traveling to the Texas–Mexico border in early 2000, shortly after reading Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Crossing. Inspired by McCarthy’s bleak, hypnotic prose, I wanted to make pictures that evoked the same sense of frontier edginess and melancholy.

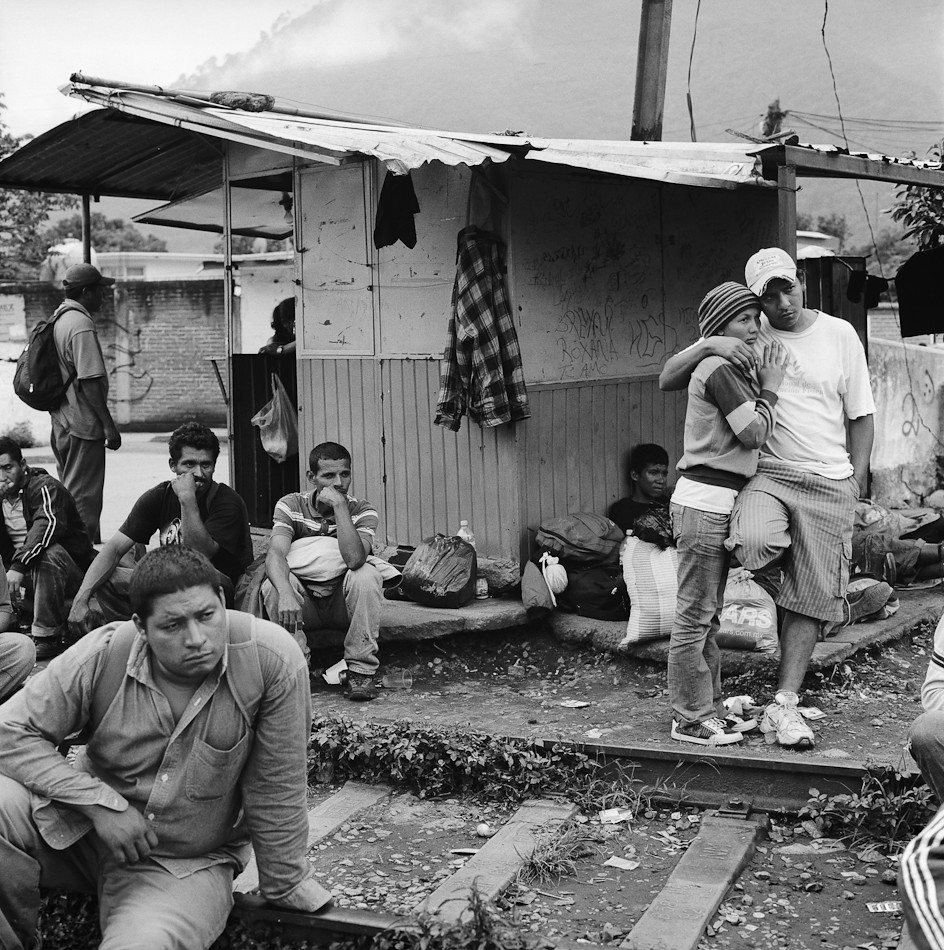

I had been aware of the migrant story in Mexico for a while. My friend and neighbor – a Washington Post photographer - had covered the story as part of an ongoing project about Mexico-related issues. But I never really paid much attention to it. Then I read Sonia Nazario’s Pulitzer-prize winning book, Enrique’s Journey, about undocumented Central American adolescents whose mothers had left them when they were very young to look for work in the United States. Predominantly from El Salvador and Honduras, these mostly teenage boys traveled by rail across Mexico in search of their mothers in the United States. Along the way, they faced a multitude of dangers. The book had a profound impact on me - I cried like a baby. It really got to me. Although it's nonfiction, the narrative was so compelling that in many ways, it read like an epic adventure tale.

Personally, the story resonated with me on several levels: I was in complete awe of these youthful, cheeky migrants who, relying mostly on their wits and the occasional kindness of strangers, were able to traverse stretches of deadly terrain in the nearly 2000 mile journey across Mexico. They had a singularity of purpose and determination, a kind of brazen resilience I admired. I’d grown up on the adventure tales of Jack London and Mark Twain, and then later, on Cormac McCarthy’s border stories. To me, there is no storyline more romantic or compelling than one involving some kind of youthful odyssey across a hostile wilderness. I always root for the underdog and these Central American migrants represented the quintessential underdog.

TID:

Can you describe what was going on in your mind as the image took shape, and then also what you were thinking when you made the image?

MICHELLE:

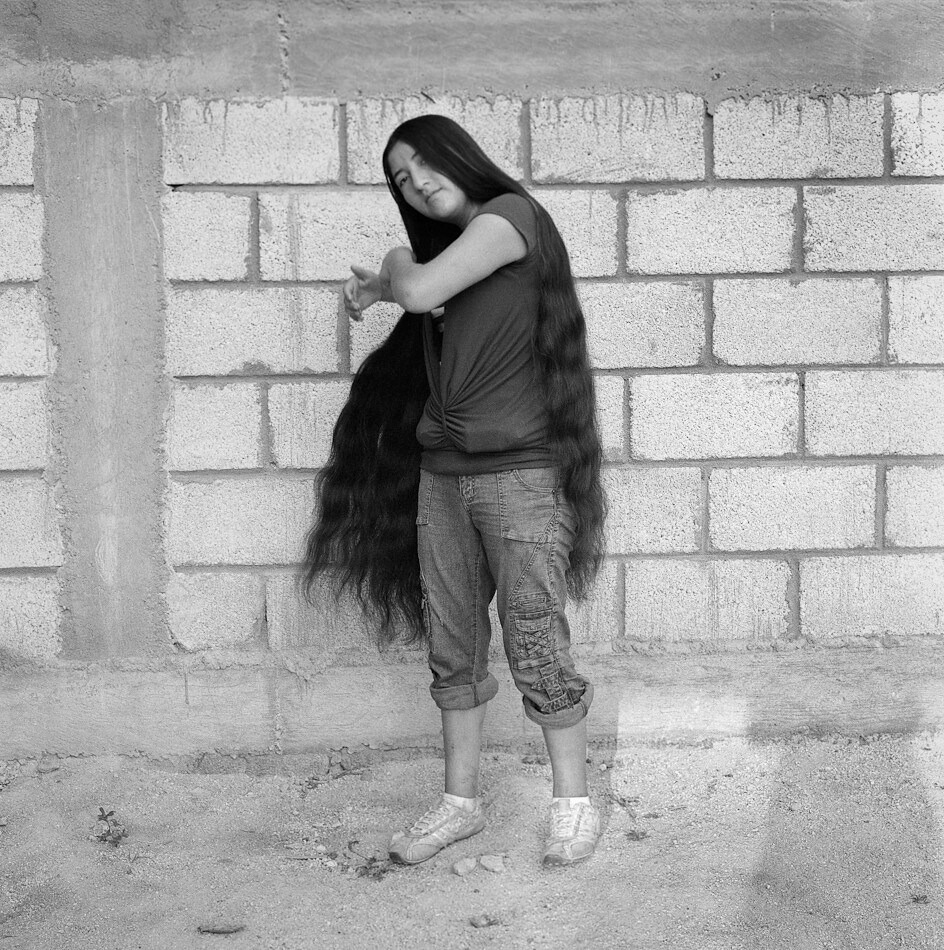

I took the photo the morning after my first trip riding on top of a cargo train. I set out with a group of mostly Salvadoran migrants I had met at a shelter in Arriaga the previous day at about 3 o’clock in the afternoon. We arrived in Ixtepec, Oaxaca around 3:30 in the morning. After a quick pat down by volunteers at the gate of the shelter compound to make sure no one was carrying weapons, we were handed bowls of steaming chicken soup, hot tortillas and Cokes. One of the shelter workers carried a sleeping pad and a sheet up to the concrete slab roof of the main building for me. He said the roof made a good sleeping place because it got a nice breeze and therefore, fewer mosquitoes. I climbed the ladder after him, rolled the pad out between spikes of rebar, and within seconds of lying down, I was asleep.

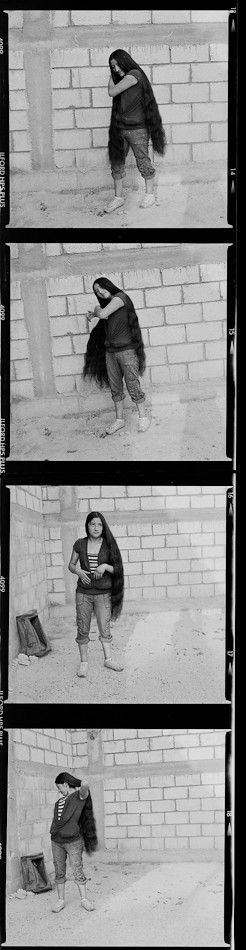

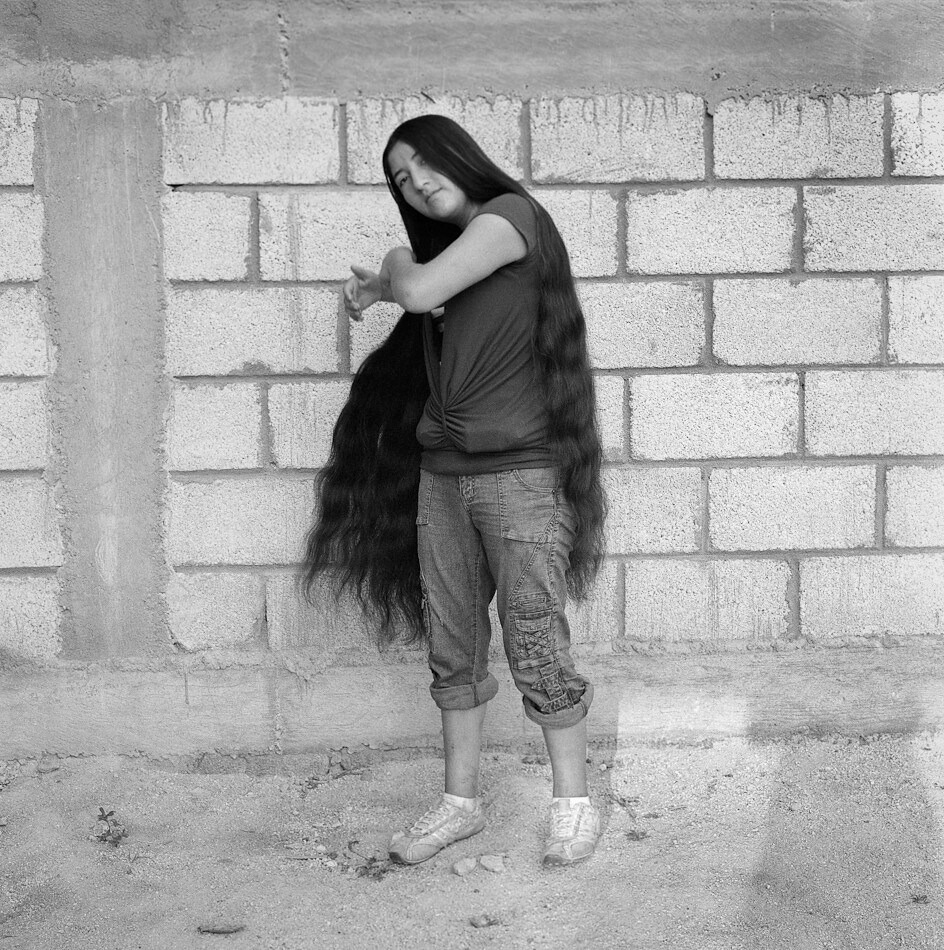

I must have been dreaming that I was still on the train, that I was falling; I could hear the metallic clang of boxcars slamming. I woke up flailing. From the roof of the building, you could see the shelter compound below and the railroad tracks just beyond the gate. It was morning, well past sunrise. I saw the girl brushing her hair. I jumped into my jeans and sneakers, grabbed the Bronica, and scrambled down the ladder, taking several determined strides across the dusty courtyard. I was barely awake. In those few seconds as I pocketed the lens cap, yanked the black slide and cocked the shutter, all I thought about was 500 at f/8.5, compose, focus, shoot. I didn’t even bother taking a meter reading. I didn’t think I would have time and I didn’t want to miss that picture. There was a kind of magical realism to the scene, heightened by the fact that I was still half asleep.

TID:

What were some problems or challenges you encountered during the coverage of this event, and how did you handle them?

MICHELLE:

Initially, I had planned on traveling to different migrant shelters to take large format portraits of Central American migrants. Riding la bestia wasn’t part of the original plan (migrants call the train la bestia - the beast - because of the number of people who have been injured or killed while riding it). I brought an Ebony 4x5 field camera and all the gear that goes with it, which is a lot to schlep. At the last minute, and mostly as a backup plan, I packed my Bronica 6x6 and one lens. I thought I had a ton of 120 film stashed in the fridge, but it was mostly leftover 35mm from my film days shooting weddings. The night before leaving for Mexico, I realized that I only had 23 rolls of 120 film.

Right away, I knew the large format approach wasn’t going to work. It was about 95 degrees in southern Mexico; ducking under a black cloth felt like sticking your head in an oven. The equipment was more of a hassle than a tool. It was uncomfortable, awkward and not really appropriate for the situation. Once I started talking to migrants and hearing some of their stories, I realized I had to do the ride with them. So I stashed the 4x5 gear at the shelter in Oaxaca. I basically jettisoned everything I had brought with me except for a small Lowepro pack and a little Tamrac shoulder camera bag into which I crammed a change of clothes, a toothbrush, the Bronica and my 23 rolls of film. With a lighter load, I backtracked by bus to Chiapas. Those were the basic hiccups associated with the first trip.

TID:

Was there anything that you learned or put to use in later assignments that came about from this experience?

MICHELLE:

Subsequent trips were somewhat easier in that I had most of the logistical kinks worked out. First trips are challenging because you’re trying to get your bearings. There is a certain amount of trial and error and the occasional false start. On the other hand, you often “see” better because everything is new and exciting. In many ways, though, even that first trip felt like a seamless integration with the story once I’d settled on what to do and how to go about it. I quit my newspaper job in 1988 to study Spanish in Guatemala. I worked with a human rights organization in Nicaragua, and then later, as a stringer for Reuters in Managua. So even though I had never been to this particular region in Mexico, I’ve spent the past 20-plus years circling back to this one culture.

Language is a conduit for cultural empathy. At some point, you are no longer mechanically translating from your native language, with its accompanying mindset, to another. The more proficient you become in a language, the more culturally nuanced you become. It goes a long way towards being accepted by the people you are photographing. You begin to understand what it is like to be them. I personally never want to work in a country where I don’t speak the language. As important as it is to get to know people, I want them to get to know me as well. I don’t want to do that through an interpreter. I’ve always felt that language is the most valuable tool in my bag.

With few exceptions, I shot the entire project with one lens: a normal focal length 80mm f/2.8 (normal for the 6x6) at a distance of about an arm’s length. The image of the girl brushing her hair is as close to hit-and-run, guerrilla-style tactics as I ever get, seeing as I didn’t know her. I’m not sure if she had come in the night before on our train, maybe several boxcars down or if she had already been there. I just saw the moment and went for it. But typically, I spend days with the people I’m photographing, so they already know me and understand what I’m doing.

TID:

Did you approach people randomly? How did you approach them, or were you introduced?

MICHELLE:

The migrant shelters themselves function as a kind of a vetting process; the polleros (smugglers) are not allowed inside the shelter, which tends to weed out some of the more unsavory characters. Once I’ve been cleared and given permission to take photographs, it’s assumed that I don’t represent a threat. People are actually very open. They are eager to talk, and with few exceptions, don’t mind being photographed.

I have a genuine curiosity about people and a completely non-threatening demeanor. Sometimes, I get the feeling I remind people of someone they know – a kooky relative, a funny friend – someone familiar. Everyone seems to know someone who looks like me. I’m fairly uncomplicated, in the sense that my visceral reaction to people, regardless of the situation is consistently childlike. My dad used to say, “You either love or you hate. There’s just no middle ground for you.” And in a way, that’s consistent to what/who I choose to photograph. I think people respond intuitively to what you project. They can tell if you seem nervous or afraid. They can sense that you’re on their side, that you’re genuinely interested. I simply avoid subjects/themes/stories that are reprehensible to me. For me, it’s always personal. There is no pretext whatsoever to objectivity. I’m highly subjective. You would never find me on the Republican campaign trail, for example.

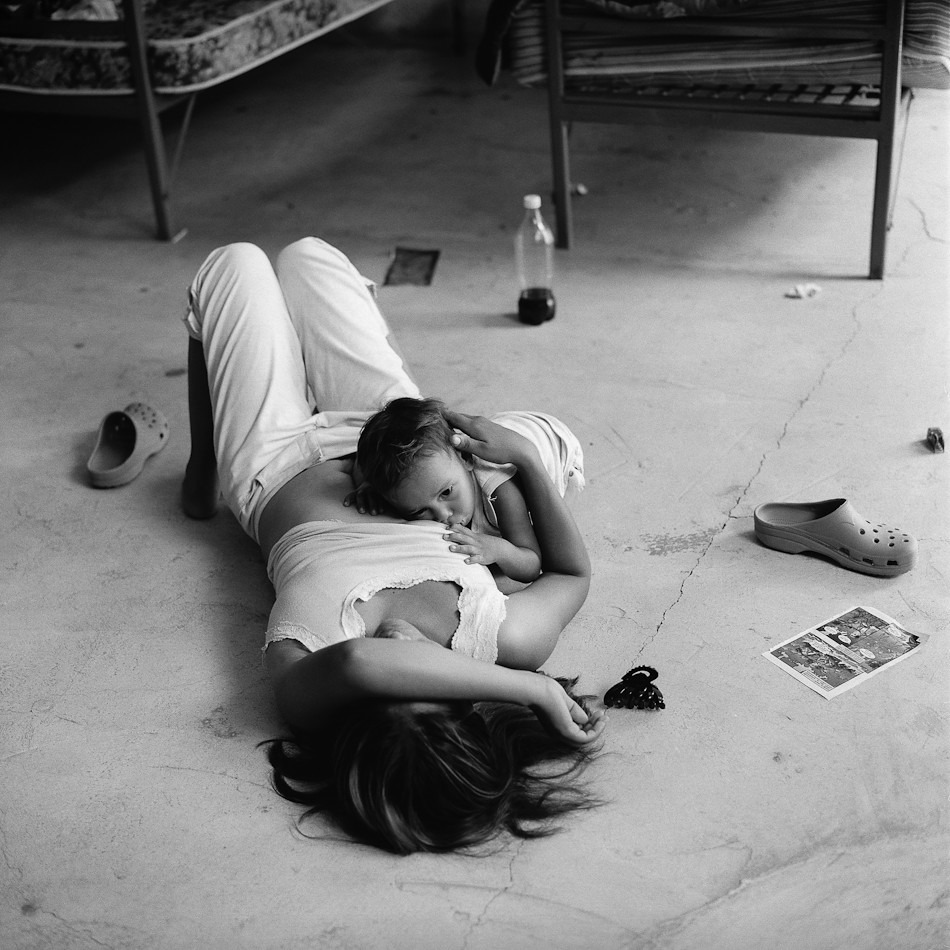

If Destino were yet another study in human misery, it wouldn’t have taken such a hold on me. I was aware early on of our capacity for brutality towards one another. I’m always searching for something redemptive. Although much of the storyline is grim and heart wrenching, there are moments of beauty as well that serve as an affirmation of humanity.

Access was surprisingly easy, at least at the various migrant shelters I visited, once I had introduced myself and explained what I was doing. There is a genuine desire on the part of both church and lay workers serving the migrant community to disseminate the story of the migrants’ experience within Mexico.

For the record, I have only ever done one leg of the journey by train – the thirteen-hour trip from Arriaga to Ixtepec in Oaxaca. I’ve done that same trip three times, at different times of the year, under various weather conditions. It changes every time. For personal safety reasons and because of financial limitations, I’ve never traveled beyond the first leg of the journey by train. Having a fixer or at the very least, a driver who could meet me at points along the way would have been extremely helpful, especially considering the current situation in Mexico as Central American migrants are targeted for kidnapping and extortion by various criminal organizations operating with impunity. But I had to weigh the benefits of what I might be able to document against the potential risk involved. One of the migrants I traveled with asked me, “What are you trying to prove? You’ve seen and photographed what it looks like. You’re just putting yourself at risk.”

TID:

How was it working under the circumstances (i.e. weather, moving trains, lots of people, etc.)?

MICHELLE:

I’m chasing the perfect ride - one that leaves at a time of day that guarantees the most hours of daylight with an interesting cast of characters. I had a few rules about the circumstances under which I would travel: I wouldn’t leave in the evening, because most of the trip would take place at night. I wouldn’t hop a moving train and I wouldn’t ride in the rain (It’s really tough to shoot with a Bronica in pouring rain). By my third trip, I'd broken all of my rules.

There is no set train schedule and not much to do, except talk and watch American movies dubbed in Spanish on TV. The heat is oppressive. At night, the sticky air swarms with mosquitoes. The biggest challenge is often battling the tedium that goes with days of waiting – not knowing when or if the train is coming. But I spend that time making portraits and getting to know people. I’ll bond with a group, which is basically a very loose coalition that forms at the shelter over a period of days. By the time the train finally arrives, I feel like I’ve shared things that I haven’t even told people I’ve known back home for years. I do have a camera and an agenda, but aside from that, it is very much a shared experience.

TID:

Were you anxious or ever down during the travels? How did you keep your spirits up?

MICHELLE:

I get homesick. I check Facebook a lot at Internet cafes. I miss my dogs most of all. Sometimes, I’ll look at the photos of my friend’s dogs on Facebook. It’s like emotional comfort food. I smoke and then when I get back home, it takes a while to quit. I start to burn out after about three weeks. I may take a day off, just to lie around a hotel room reading or watching TV. Then I’m good for maybe another week. After that, I feel like I’m just limping towards the airport.

I’m not sure of any advice I might have for someone doing similar work. Have a strong bladder? Personally, I would not have undertaken this project if I couldn’t speak Spanish well. I know I’m mostly interested in work that’s either allegorical in meaning or idea-driven. I think the trick is to find an idea or a story that transcends its literal meaning – something that goes beyond “people doing things” reportage, and then find a way to convey that idea. Look for protagonists. They don’t even have to be likeable. But they should be interesting and more complex than just the amorphous downtrodden.

:::BIO:::

Born in Jerusalem, Israel, Michelle Frankfurter is a documentary photographer from Takoma Park, MD. She graduated from Syracuse University with a bachelor’s degree in English. Before settling in the Washington, DC area, Frankfurter spent three years living in Nicaragua where she worked as a stringer for the British news agency, Reuters and with the human rights organization Witness For Peace documenting the effects of the Contra war on civilians. In 1995, a long-term project on Haiti earned her two World Press Photo awards. Since 2000, Frankfurter has concentrated on the border region between the United States and Mexico and on themes of migration. She is a finalist for the 2011 Aftermath Project for her project Destino, documenting Central American migrants and a 2011 Top 50 Critical Mass winner. Destino was published in Burn 02 and shown in Perpignan during the 2011 Visa pour l'Image festival.

To contribute to the Desinto project, please visit its Kickstarter site. You can see more of her work here:

Website: www.michellefrankfurterphotos.com/

Next week we'll take a look at this image by Thierry Bigaignon:

If you have any suggestions or if you want to interview someone for the blog, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting.