Spotlight on Mark Zimmerman

Feb 13, 2013

TID:

Thanks for taking the time to talk with us. Please tell us a little about the image and the backstory.

MARK:

First, I want to say that I am honored to be a part of this blog. I have been following the posts for some time and have enjoyed reading about the stories behind each image.

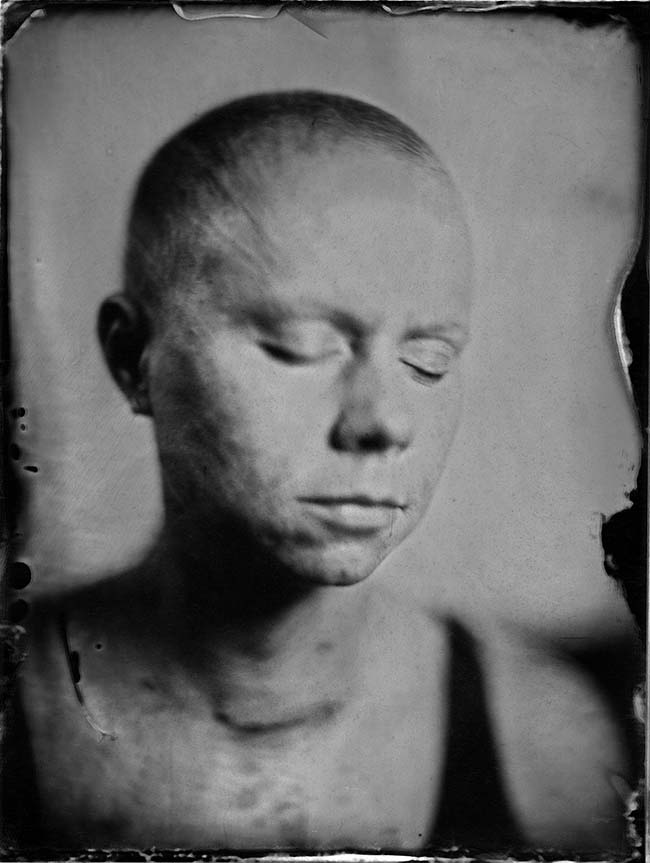

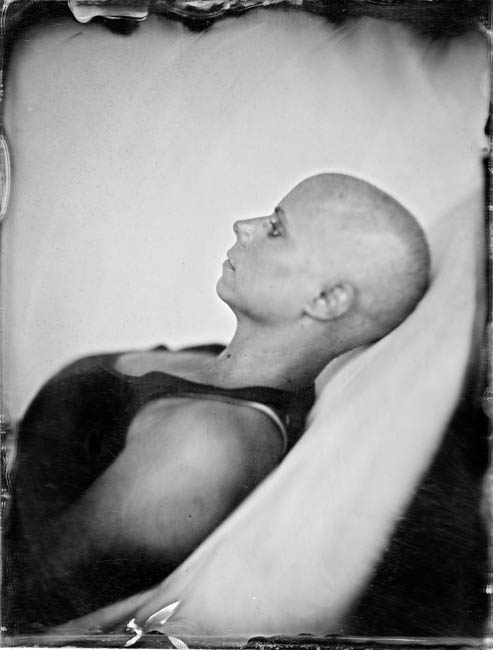

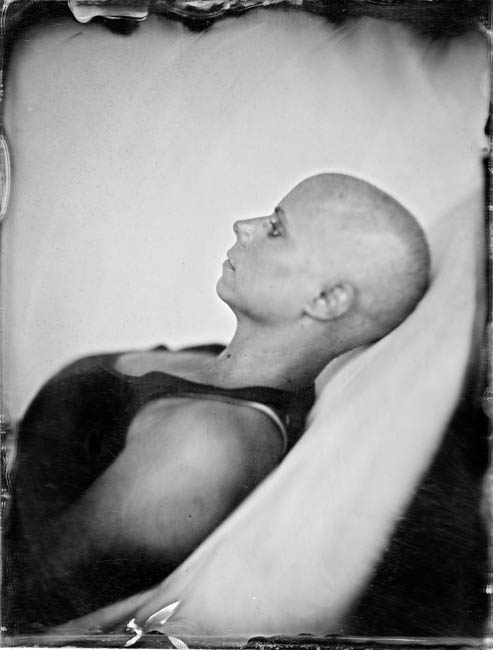

In the summer of 2010, my wife was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer. During this time I was about to start my last year of graduate school at the University of Oklahoma. This image is one I made right after my wife had her thyroid removed due to it being cancerous. Now she was dealing with two types of cancer. She was still recovering from her breast surgeries and several doses of chemotherapy. The news of her thyroid cancer was just another setback during this insane time in our lives. This image captures my wife's strength during her treatments and reminds me how thankful I am for her recovery.

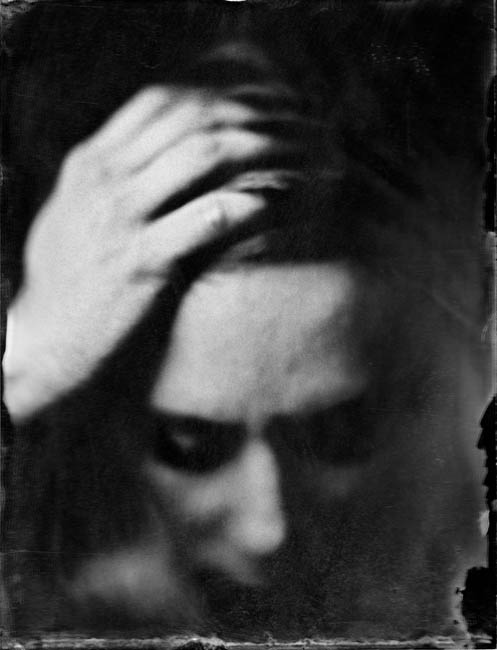

Even though the plate is technically not perfect (really, none of them are) for some reason it sums up the whole process of what we were dealing with at the time. I was juggling grad school, working full time, being a dad to my two kids, and then trying to be a supportive husband to my wife who was dealing cancer. These photographs are some of the most honest images I've ever made.

TID:

Can you please talk a little technically about what you're doing since this is an unusual approach - mirror plates?

MARK:

The photographs I have created are comparable to daguerreotypes, one of the first photo processes invented in the nineteenth century. Instead of my images being on polished copper plates coated with silver, I decided to use mirrors to help communicate multiple layers of meaning related to her disease.

The mirrored plates in A Fragile Existence are 6.5" x 8.5" in size. When mounted on the wall, the viewer will approach and interact with the images. When light is thrown across the silver on the surface of the image, a negative of the subject is formed, but when a person moves in front of the photographs, their body forms the positive. The viewer fills in the shadows while standing directly in front of the mirrored plate and his/her face or body blocks the dark tones in these photographs. The viewer is left with documentation of my wife going through physical changes over the past ten months. I want them to reflect on their own mortality.

I made the conceptual choice to create these images of my wife on actual mirrors. These images appearing on thin fragile mirrors relate both to the delicateness of life and the vanity-minded society that America has accepted as the norm. As a viewer interacts with photographs of my wife’s fight with cancer, the impermanence of life is reflected. The thin, brittle unframed mirrors represent a metaphor of our daily lives.

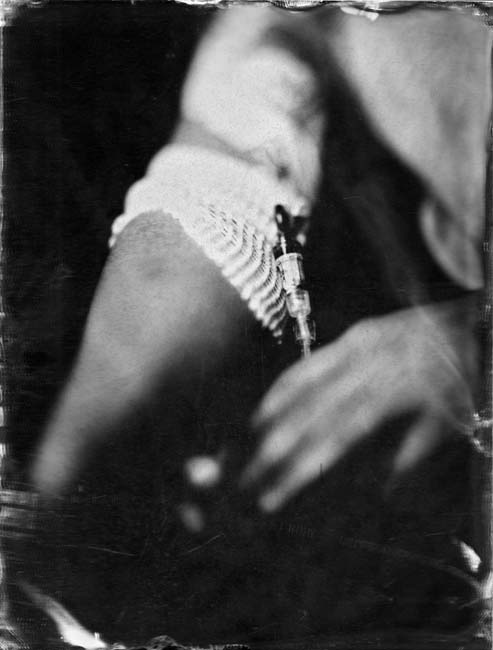

I used this process to make the images of my wife. Some of the chemicals used were collodion, silver nitrate, and ether. All have a history of medical use. Collodion was once used as a way to mend wounds in the nineteenth century. It bonds to slick materials, such as glass, and forms an adhesion with the silver nitrate, which makes the plate light sensitive. In a diluted form, silver nitrate was used in the past as a way to protect against infection and blindness in newborns. Ironically, if I were to splash it in my eyes at the dilution required to make these images, it would cause blindness. The volatile chemical ether is highly flammable and at one time was used as a common anesthetic.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this body of work?

MARK:

There were several challenges with this project. At each stage, I would struggle with the decision to bother my wife with my project, especially if she didn't feel well. Every single photo had multiple steps where I had to prepare the chemicals, clean the plates, and adjust the lighting. Sometimes the images wouldn't work. Other times, plates would accidentally drop from my hands and shatter on my garage floor. No duplicates. Each image is one of a kind.

Truthfully, making the photographs was at times a positive distraction from all of the craziness. Although I can't speak for my wife, it helped me both hide and confront my fears about her illness. The camera became therapeutic. A way for me to share what someone goes through when a loved one struggles and survives a disease.

I was worried about objectifying my wife as merely a subject when it was a very personal journey she was traveling. So I would research other artists’ work, their representation of disease and dying helped facilitate my photographs. Both Sally Mann and Eugene Richards’ fearlessness in their work assisted me overcome my fears. Sally Mann has been creating images of her husband over the past several years as he fights muscular dystrophy. Her depiction of her husband’s journey really resonated with me and revealed to me a hope that my project could be inspiring and not depressing.

Likewise, Eugene Richards' did a collaborative project in the 1980s with his companion Dorothy Lynch who was battling breast cancer, which resulted in a book called "Exploding in to Life." Richards' images were a true representation of the seriousness of breast cancer. It was one of the first times a photograph of a mastectomy was ever published. As a New York Times review states, "his pictures have the virtue of showing something that society has relegated to the shadows. To see what Lynch's mastectomy looks like, to see her without hair, to see her bent double from chemotherapy-induced nausea - none of this is pleasant, but it demystifies a disease that, visually, has been left to the darkest realms of the imagination. "

This book had a huge influence on my work, and I know it helped me overcome my reservations about doing the project.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

MARK:

I would talk with her before I ever brought out my camera. I wanted her to tell me if she didn't feel like messing with it. We also collaborated on the type of pictures I would shoot. Many of the images in the project are revealing, whether showing her scars, aftermath of her mastectomies, etc. With every image I shot, I wanted her input. As a former photojournalist, this connection was something I had never experienced, but the intimacy was important for this project to work. The pictures were just as much hers as they were mine.

Several times I considered scrapping the whole project when things got bad. One incident occurred when she first began chemotherapy and was forced to go to the emergency room with debilitating nausea. However, it is heartening to know that we fought through the negative aspects of the disease by working together on these shoots. I was terrified when I watched them pump chemo into her veins, or when I waited for the countless hours she was in surgery. This collaboration speaks loudly about our love and trust for each other.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

MARK:

First, it was extremely difficult to pick one moment that spoke to me. All of these plates together represent one moment, so I really don’t have a favorite. The images are ideally viewed in-person and as a collective.

Typically, I would shoot a plate every other week depending on how my wife felt and what she was going through at the time.

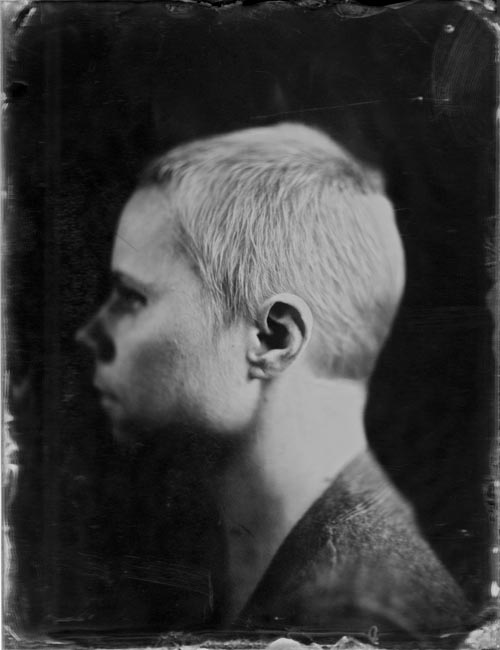

I knew I wanted my first plates to show how her treatments affected her. Each time I photographed, I wanted her input on what aspects of her illness were important to capture on a plate. She lost her hair very fast after starting chemo, so this change was an essential element to depict. It encapsulates the insignificance of vanity and has a humbling effect on the viewer.

The main plate comes at the apex of her battle and represents the moment of her greatest struggle throughout her treatments. Right after she had her cancerous thyroid removed, she was readmitted to the hospital for a week because her calcium had fallen to an extremely low level. This image speaks about not only her strife, but it also illustrates her strength. I knew she was going to beat this.

TID:

I'd love to hear your wife's thoughts on this. Meredith, could you talk about what it was like for you to be documented by your husband?

MEREDITH:

Being documented throughout my treatments and surgeries was cathartic for me. The images allowed me to focus on each phase of my journey and vanquish my demons. I am a fighter! When faced with the diagnosis of cancer, I saw our project as a way to hopefully alleviate other’s fears of the unknown. It also was important for me to show how like everything else in life, this is just a process and a hurdle to overcome. The pain, nausea, and disfigurement is the price I was willing to pay for the reward of more life, more understanding, more patience, more journeys, and more love. Surgeons can and have worked miracles in my life, and even though everything has been remolded, I couldn't be more pleased with the outcome!

TID:

What have you learned about each other in the process of making images like this?

MEREDITH:

I learned that although the patient has pain and discomfort, it is equally as hard on the patient's family. Your spouse struggles to comfort you at your lowest while they internalize their fears and doubts. They demonstrate strength and hold you while you cry. Mark is my partner-in-crime and for better or worse will be there for me. I could not be prouder of the work we created!

MARK:

I learned that my wife is one of the strongest individuals that I have ever met. She put her full trust into me as a photographer and a husband. I’m not sure I could ever be that brave if the table was turned.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers who want to do this type of work?

MARK:

Do it for the right reasons. Don’t put your subject in a vulnerable position. Communicate and be honest on what you are trying to portray with your work. I would also encourage photographers to research what they are about to document. Look at how other photographers have overcome their fears.

MEREDITH:

You must gain the trust of your subject. This implicit trust is the only way to achieve intimacy with your subject. A person battling a disease is searching for a way to make a difference. They are screaming inside to be heard. We want to make a statement that is unique to our individual fight. It is up to the photographer to listen and document.

:::BIO::::

Born in rural Oklahoma, Mark Zimmerman is an award-winning photographer who has worked in editorial and commercial photography for the past 20 years. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Photography in 1993, and received a Masters in Education in 1999, both from the University of Central Oklahoma. In 1994, he started full time at UCO as the director of instructional photography, responsible for the upkeep of the darkroom and studio equipment and teaching students the basics of the darkroom. He was chief photographer for the Edmond Sun in Edmond, Oklahoma for four years. He has worked as a freelance photojournalist for the Associated Press, The Tulsa World, The Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Getty Images and other major publications.

In May 2011, he received a Masters of Fine Arts degree from the University of Oklahoma and is currently an assistant professor at the University of Central Oklahoma in Edmond, Okla., where he teaches courses in photography.

You can see his work here:

As well as a video portion of the project: