Spotlight on Logan Mock-Bunting

Jun 27, 2012

Originally published 07/09/2012

After publishing last week, we learned that the diver featured in this image - Nick Mevoli - had passed away. The Image Deconstructed staff wanted to revisit the image to pay respects to Nick and his family. Our deepest condolences to all who knew and loved Nick..

TID:

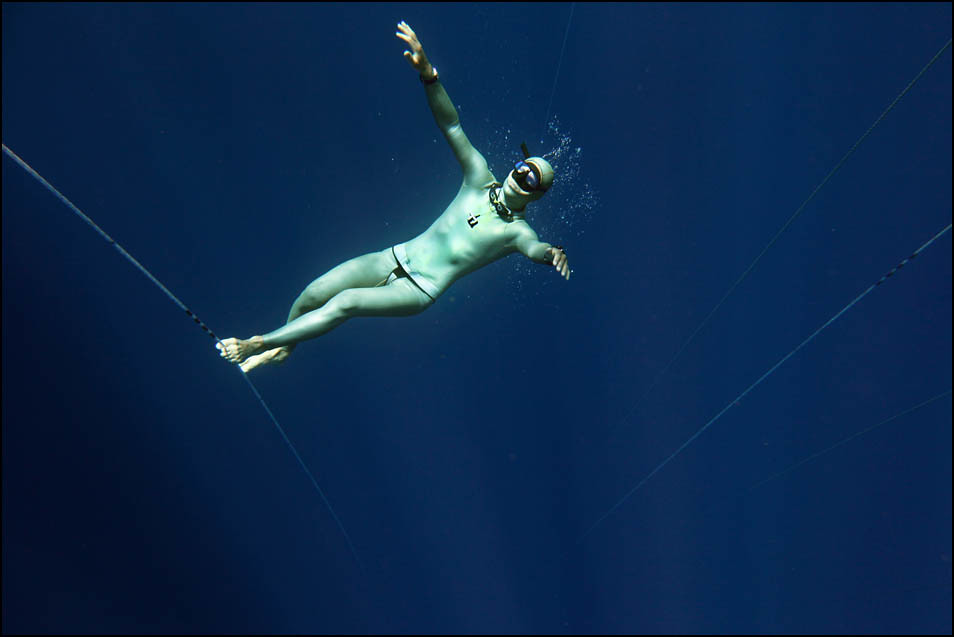

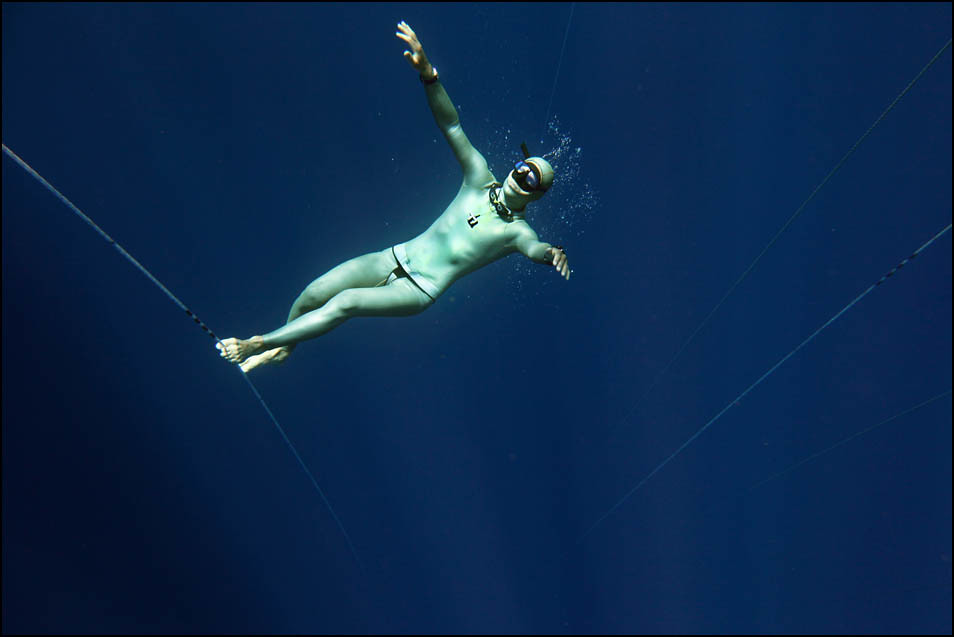

We'll look at this image by TID co-creator Logan Mock-Bunting, which he made during a freedive competition where several freediving records were broken. Please tell the backstory of this image.

LOGAN:

I've been freediving (breath-hold diving, no SCUBA or rebreather gear) for several years, and a group of friends have spoken about this event off Grand Cayman Island for quite sometime. Called Deja Blue, it features workshops/training on freediving techniques, as well as an officially sanctioned international competition. One of my good friends, Ashley Futral Chapman, was attempting to break a world record. She and her husband sailed down to the event this year and told me if I got down there, I could stay on their boat for free. I had enough frequent flyer miles saved up for a ticket down there, and it just seemed ridiculous not to go.

After I got there, however, the logistics staying of staying on the boat weren't going to work out. I needed to be with the participants as much as possible, so I ended up rooming with the fellow named Nick Mevoli -- he is the gentleman pictured here.

TID:

You mentioned you thought a lot about some of the discussions here on TID while you were shooting this work. What were some of your thoughts?

LOGAN:

Although I have been freediving for years, I'd never been to a competition. I had seen a few images and videos, so I had a basic idea of some visual possibilities, but didn't know what to expect once we hit the water. Since I was now staying with the participants, there was a lot of downtime to just talk and ask questions. I was very open with the fact that I didn't know how things worked, and asked lots of different folks what THEY thought would be interesting to look for. While they talked, I took note of many of the things we've talked about here on TID, such as patterns in behavior and repetitive actions. I talked to several different participants, asked them similar questions, which ultimately gave me a broad outline of the event.

For example, I would ask someone to describe the timeline of a day at competition. They would say, "After we get to the dive spot, the crew sets up the rig. There's lots of action and you should be able to get good images." I would ask why, and they would say, "Because there are crew members swimming around at different depths with lots of lines going everywhere; there is just a lot happening." So I would follow up with, "What about on the boat? What are competitors doing while the crew sets up?" (It is no secret that often the most intriguing images at any sports event happen before or after the main competition. "Go early, stay late" as we've talked about here.)

Many people would say things like, "There's not much action on the boat before the competition. People are just chilling out and getting mentally psyched up for the event." So then I would ask much more specific questions like, "Well, what do competitors do to get ready?" And most folks would talk about listening to music, stretching, meditating etc.: activities that allow divers to get their heart-rates down to enable them to stay deep longer, using less oxygen. It seemed like there were interesting aspects of the preparation, so I kept asking the question to different folks, looking for nuggets of info.

Finally one of the guys who was also shooting video for the organizers of the event said, "Oh, there is this one cool thing I've never seen anyone do..." and he went on to describe a guy "tightrope" walking up one of the dive lines. "That might look cool to you," he said. It wasn't a "Eureka!" moment, but when I was in the water on competition day, and I saw Nick setting up for this routine, I knew exactly what it was and raced over, hoping I could get in position for it.

TID:

I can imagine there being a ton of complications in this shoot. Can you talk about some of the problems you faced and how you overcame them?

LOGAN:

Ugh. A huge part of the trip was about problem-solving. I mean, it was a wonderful experience, but nothing about it was easy.

As I said before, even the most basic plans (where to stay) didn't work out, which totally became a blessing. Instead of just being this media dude who came to competitions, I ended up really being part of the group, since I was eating, planning, sleeping, staying with them ALL the time.

This was great for several reasons:

1) We had tons of communication, which led to greater trust (the judges and crew would NOT have been ok with me swimming all over the competition area if they didn't trust me).

2) I had lots of time to ask questions and get help in figuring out logistical problems that came up occasionally.

3) It made things SO much more fun. I didn't feel like I was just on assignment, I was also experiencing the event, if not quite participating in it. I don't know about you, but 99% of the time I shoot better if I'm enjoying myself and/or not stressed out.

As far as shooting underwater -- it is a massive change from shooting on land. With shooting underwater, you have to understand that light acts differently in water than air. Color shifts and drops, distance appears different, even focusing is a completely different game when photographing through air (in the housing) and then through water to get the image of your subject. So one really has to do a ton of studying, research and practice in the water. When you are starting to photograph in the water -- even if it is "just" in a pool or calm water -- ALWAYS have a buddy. This goes triple when diving or freediving. I couldn't have just shown up and shot this as my first assignment underwater.

Oftentimes, I'll go out and shoot in horrible light and visibility, not because I think I'll get great photos, but because I want to experiment, so I'll have more options and ideas when conditions aren't great. If I just shot in a crystal clear pool all the time, that really wouldn't prepare me for 90% of the real-world experiences I encounter in the ocean. So, knowing your gear and what conditions it can handle, how and where you can "push" it is a foundation you just have to learn.

I think this is just as applicable for above water, too. Look at Bryan Casella's previous column. He talks about how even when he is shooting a hail-mary, he's pretty sure what he will get in the composition, because he practices so much. Same thing is true for underwater.

Before auto-focus became fast and prevalent, Walt Unks, a photographer at the Durham Herald-Sun (where I interned as a student), used to stick a 400 out his window and follow-focus cars as they drove on the highway. That was his practice focusing for sports events. I remember he could get a track runner, moving towards him, in focus over every single hurdle on a sprint. He practiced with his equipment, and it showed.

TID:

What type of equipment did you use?

LOGAN:

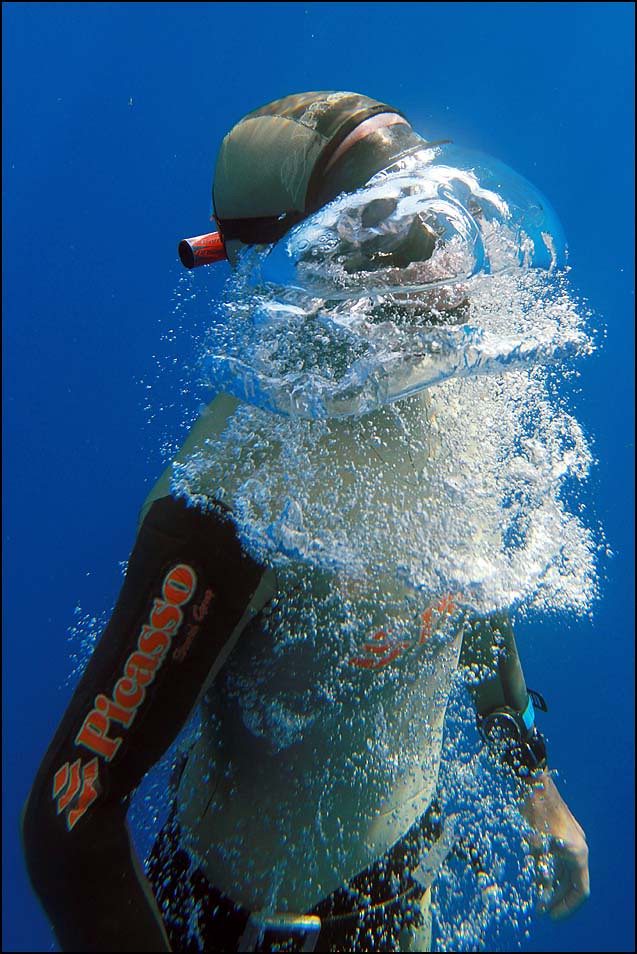

My equipment included an underwater "bag" that sealed tight and was depth-rated for 30 meters. I did NOT trust it enough to dive deeper than 30 feet, so I used this for surface and shallow dives. The biggest disadvantage to this was not being able to dive very deep, and not having a light source. As I mentioned, light loses certain colors (and intensity) the deeper you go. In other words, it gets darker and "bluer" as you descend. So I also used an Ikelite water-housing with a dome port. The advantage using the housing is that it can go deeper and I can attach strobes to it, which gives the images a completely different feel.

It also has disadvantages: it's heavier and bulkier. Getting around is a huge issue in the water, so added heft and drag was a serious consideration. The port (part of the housing in front of lens) on the Ikelite was a dome port - allowing for wider angle images to be shot. This port is very difficult to use above water, as waterdrops bead up and cause smudges on it, much more than a flat port (like the UW bag had). The dome port is also more likely to pick up reflections, glares and refractions. So there were times and places for both housings.

TID:

How did you handle the execution of the dive?

LOGAN:

One of the biggest hurdles shooting underwater is breathing -- or not! I decided to freedive while covering the event for several reasons. While freediving you descend to depth and then come back to the surface under one breath. If I were to have worn SCUBA, I wouldn't have been able to pop up-and-down without having to do safety-stops to avoid decompression sickness - known more commonly as The Bends. This very dangerous illness is caused by the body staying internally at the same pressure while the outside pressure (in this case the water around and above the diver) changes intensity. Gases in the blood can "bubble out" and can cause all sorts of havoc, including paralysis and death.

Since I knew I wanted to get both the action of the dive and the reaction on the surface, SCUBA tanks would not allow this. Freediving was the only way I could make the same transition that the subjects of the stories were making. I also believe that authenticity can come through in an intangible way in photographs. If you are only witnessing things in a removed way, the images often project that removal. But when the photographer is going through what their subjects are going through, somehow it translates. Maybe it is just that subjects trust you more when they see you aren't "cheating," or afraid to live like they live. I don't know. But it was important to me to be authentic, and I thought participating in the same sport they were - in the same way - was critical.

The other problem is something easy to take for granted on land: simply getting around in the water is difficult. I'm very comfortable in the water, and a fairly good swimmer. Getting from point A to B was always a challenge in the competition though. For one thing, I had to pay attention to what was happening under me, above me, to each side, as well as in front and behind me. There were constantly athletes and staff acceding, descending and cruising from spot to spot.

TID:

For those of use that aren't familiar with the competition, can you explain a little about what goes on?

LOGAN:

The competition space is basically a large X -- two very long carbon fiber poles which have lines, weights, counter-weights, and depth platforms that hang from the ends. Someone said, "It must look like a crazy mobile above a baby whale's crib" and I think that is a good metaphor. While the competitors are staging events on two of the ends of the X, diving to a small platform where they grab a flag at their target depth, there are other lines holding counter-weights, as well as lines for other athletes to warm up and acclimate. There are things going on ALL around, at all times.

Covering a freediving competition is very difficult. There is never enough space on a dive boat, with so many people and so much equipment everywhere. Getting around to find viewpoints is cumbersome, and then you do not want to disturb the athletes; so much of freediving is mental preparation, and the last thing people want is to have their concentration or meditation interrupted by a camera in their face. A photographer has to be respectful, graceful, subtle, and quick.

In the water and around the rig things are much more hectic. At times, there are dozens of people around the rig, wearing long flippers and zipping up and down. Even worse, once the athletes begin their dive, if anyone touches them, even slightly, the athlete is disqualified. The Safety divers are very active, yelling to each other to verify times, plans, and strategies. The staff is communicating how to set the lines to depth and when the next dive is going to begin. It is a very frantic place.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you walk us through the moment of this week's featured image?

LOGAN:

In the instance of this image, I was waiting at the line where safety divers were acclimating to depths and waiting for an active competitor. But when I saw Nick starting to prepare for his "walk up" I remembered the conversation I had with the videographer and realized what was happening. I started swimming and kicking my ass off to get into a decent position, trying not to get in anyone's way, swim under the carbon fiber frame and avoid getting caught in any lines.

I basically got above him, tried to frame a decent composition and just started banging off frames like crazy. I was still moving/drifting from swimming over, he was moving towards me, and I knew my autofocus would have problems in the bag tracking everything, so I would fire off bursts, try and recompose, give the focus points something to latch on too, bang off more frames, etc.

What was I thinking about? Trying to stay calm and steady my hands, steady my breath (I was face down with a snorkel). Once I realized what was going to happen, I was more concerned with the physical aspects of image-making, so I tried to clear my mind of doubt and baggage and make the process all about doing the best I could at that very minute. Keep it simple. I wasn't having to think about exposure or any settings, I had all that dialed in. It was just about being present and capturing the very unique situation that was happening in front of me.

TID:

What surprised you about doing this work?

LOGAN:

The funniest thing that dawned on me was a realization I had while staying with the competitors. All they talked about was diving, diving equipment, diving techniques, other divers' experience and projects, etc. Basically it was exactly like being at Southern Short Course, LOOK3 or some other photo-gathering, but instead of discussing pixels, lenses and photo projects, all the conversations were completely centered on diving! It just struck me as amusing that once anyone gets to a certain level of an activity, and then surrounds themselves with other like-minded/obsessed people, the geek comes out. I might not be describing it well, but I bet for almost two weeks, at least 93% of the conversations somehow related to diving. It just goes to show that once a person is serious about something and really wants to be world-class, some obsession is necessary to break through to higher levels of ability and understanding, no matter what the activity!

TID:

What did you learn about yourself?

LOGAN:

I really had a wonderful time. I saw this wonderful graph online that illustrates "What People THINK Photographers do in their Life and Work" compared to what "We Really Do." It shows the obscene amount of time we spend in front of a computer editing, invoicing, etc. This shoot really was a great adventure - I am so grateful for it and the people who helped make it happen. Seeing Ashley break the World Record twice, to be with a friend who accomplishes such a huge goal is very special and amazing. The experience really taught me to enjoy what is gong on RIGHT NOW. No, things aren't perfect for a shoot -- they will probably never be. But there is something interesting happening in front of you, with you in its presence, something you are a part of; that is why you are there with a camera. Enjoy it. Be aware, don't let worry or stress take you out of what is going on. It sounds quite yoga / zen / hippy-ish, I know, but it really was one of the strongest times I was able to appreciate opportunities that photography opens up.

Also, I dove my personal best depth - 107 feet on one breath. It was really amazing to be able to push myself by feeling secure with such an amazing safety team around.

TID:

What would you tell other photographers?

LOGAN:

The biggest thing I want to stress is water safety! When young or new photographers ask about how to get into water photography, I usually tell them not to start until they have had years of experience in the water, SEPARATE from years of experience with photography. With underwater photography, you have to have lots of experience with (1) swimming/diving and (2) photography as completely isolated activities before combining them. Too much can go wrong if you get overwhelmed by one aspect and don't pay enough attention to the other.

Although I know some folks who see the photos will think many of these athletes are crazy, I want everyone to know they are anything but reckless. There has never been a death in an AIDA (the Worldwide Federation for breath-hold diving) sanctioned event. This is a direct result of the intense training, attention to safely and community that these kinds of events foster. The reason why world-class athletes come to Cayman and the competition is because of the precise safety and attention to detail. This involves multi-functioning systems: safety freedivers that meet the athletes during the critical ascent phases from 30m / 99ft to the surface as well as employing safety scuba divers at depth that can provide simple communication or intervene as a last resort.

I think people respond to some of these images because I truly love being in the water and participating in this sport. I would have never thought to go down and do this without the urging of my friends who were involved. (The entire trip was self-funded and self-proposed. I am very grateful that the CNN photo blog picked it up, so it wasn't totally a wash monetarily.)

I also feel it's important to pursue interests and relationships OUTSIDE of photography and journalism. This allows photographers not to burn out, as well as to be more interesting, knowledgeable, and relatable people. It also helps in finding different opportunities than all the folks who are stuck in the exact same orbit with only other media photographers.

For those interested, I wrote some advice on physically, mentally and preparing to shoot surf photography from the water in a Sportsshooter.com forum. The ideas can be easliy translated into getting started with any type of underwater photography.

+++

Next week we'll take a look behind this image, and others by Mike Belleme, while he documenting local skateboarding culture:

As always, feel free to make suggestions here on people you'd like to see featured, or you can contact us at: