Spotlight on Josh Meltzer

Nov 26, 2011

TID:

Josh, thanks for taking part in this. Please tell us a

little of the story and context behind this frame?

JOSH:

I left my job at The Roanoke Times, where I was a staff photographer

for 9, years after I received a Fulbright Grant to live and work in Mexico

for a year. Two prior trips to Mexico for the paper were the initial

impetus for applying for the Fulbright there. I became interested in

the work that a fellow Roanoker was doing running an NGO in

Guadalajara working with street kids in an educational setting. Many of

the kids and families that she worked with are indigenous Mexicans

that came to Guadalajara seeking work.

I framed my project proposal around a theme of indigenous migration

(indigenous Mexicans moving within Mexico). At some point during my

year I stumbled upon another NGO doing educational work in an outlying

village on the edge of the city. The community consisted of about 150

families, mainly indigenous from the neighboring state of Zacatecas. Each

family lived in a small square building built with bricks they were forming

and baking each day. There was no school, no running water, no electricity

or trash pickup.

I started shooting first at the schools where I had contacts, and then

with families that were open to my project. One young grandmother who

served as the community’s unofficial mayor welcomed me with open arms.

Like any photographer, I was curious about upcoming events, like birthdays,

quinceañeras, or baptisms, as they would serve as a break from the

monotony of brick making.

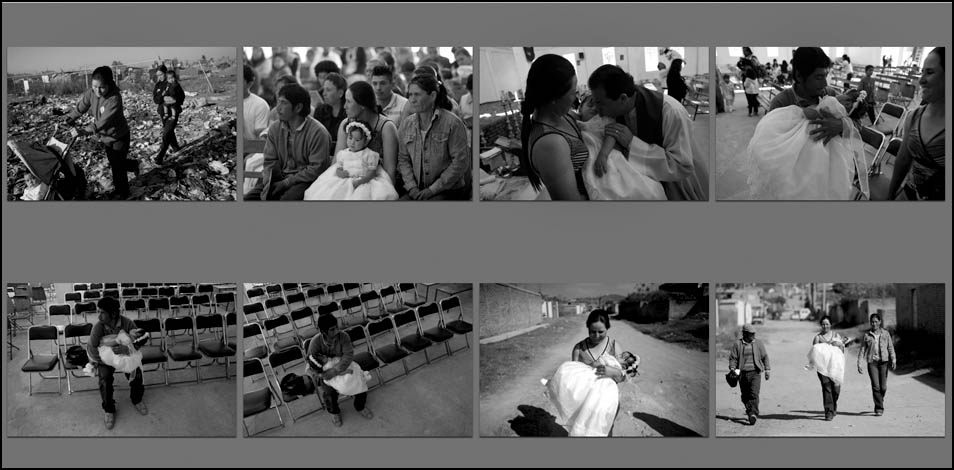

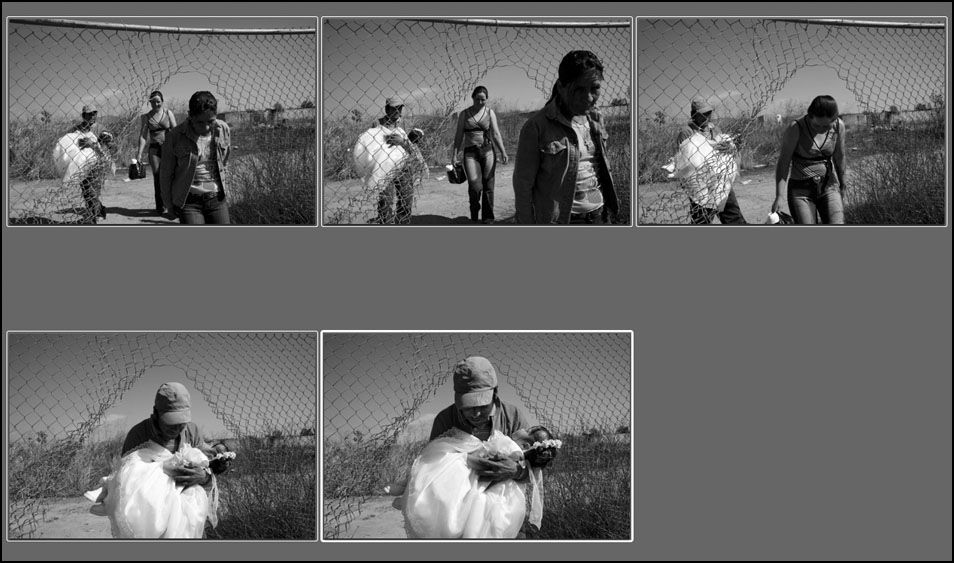

This image was made on the day of the granddaughter’s baptism. The

family walks about 15 minutes through the fence that was initially

supposed to keep them from living in this “no-man's” land back into

the community which housed the Catholic Church. It’s a simple picture -

very straight forward, and very predictable. I remembered the break

in the fence from when the family walked to the church, and knew that I

needed to reshoot it on the way back. The girl actually fell asleep during

her baptism, and slept in her father’s arms the whole way back to their home.

Of course I was very aware of its symbolism for my project. They weren’t

physically crossing from their indigenous village to the big city. We actually

weren’t really in either place, but it became a symbol for the essence of

the story.

I’d like to say one very important thing about photojournalism (that may or

may not have anything to do with my image here) that I repeat over and over

to my students at Western Kentucky University. I show them some of the

most famous pictures ever taken – icons of eras in history, amazing moments

in news or daily life, and I stress to them, even to the beginning students,

that they are absolutely technically ready to make nearly all of those images.

If I could pop them into nearly any of those scenes right now, I think most of

them would make a great photo. But, what they can’t do quite yet, and what

we all work on throughout our careers, whether as students or seasoned

professionals, is the ability to get ourselves physically in place to take those

pictures. So I ask them, “Who thinks they can get access to record intimate

moments inside a mental institution? Who thinks they can get themselves

into a situation photographing a subject using drugs, fighting or doing

something on an intimate level?” This is what we work on constantly.

It's far more important to the actual time spent pushing the button on the

camera is the time spent finding out how you’re going to physically get to

that place to make those images. This is the most frustrating thing about

photojournalism, and the most rewarding.

So back to this image – any monkey could have taken it. Frame the fence,

wait, push the button as the man walks through the opening. But it was

2 months after I first discovered this community that I was able to make

this very simple picture. We all know when there's great potential for

making powerful pictures, and all we have to do then is concentrate, pay

attention and think about what’s happening in order to shoot them. Getting

to that point of knowing there is great potential is one of the hardest parts of

visual storytelling.

TID:

This is iconic in that it communicates to people in different ways and even

transcends place, to a degree. Many people I've talked with thought that this

was from the U.S./Mexico border. What do you think about the themes that

this picture speaks to and what does it mean to you personally?

JOSH:

Yes, I think it communicates on many different levels. The first impression

that I heard from many who saw the image in a show I had at a museum in

Guadalajara wondered whether the girl had died, and thought the father was

carrying her to her funeral, which of course isn’t true – she’s sleeping.

But yes, I suppose many think that it’s at the U.S. border because that is

the story we all know about in the news. However, there are tens of thousands

of people, if not more, who migrate within Mexico and within many other

nations for that matter.

The other thing that I would say is that, as photographers we have the ability

and the right to make images that are symbols of emotions or concepts that

don’t read entirely literally. This image is of a man taking his daughter to her

baptism, not of a man carrying his daughter across Mexico to their new home

in a big city. But I think it symbolizes this concept and idea. As photographers,

we are always looking for things that can be symbols of something larger, as

long as we don’t deceive our viewers and are transparent about the circumstances.

TID:

Since leaving the newspaper, you have really demonstrated an initiative to

start several workshops, teaching opportunities, as well as creating your

own body of work through the Fulbright. Anything you've learned from taking

control of your own destiny?

JOSH:

I wouldn’t say that I’ve really taken any control over my destiny. I

suppose I did apply for the Fulbright, but like many everything in life,

things sometimes happen for an unintended reason. I loved my job at The

Roanoke Times. It was a dream job. We had a relatively huge staff, and a

very good one. We started doing multimedia way before many places did,

and were given great opportunities to learn and grow at workshops. And

we were free to do any project we could dream up - on nearly any scale.

I miss that job all the time; I miss the shooting, meeting people, my

colleagues, bosses and the community. But I also have had some amazing

opportunities to grow outside of that environment since I left.

My wife and I started to catch the “living abroad bug” and we were looking for

an opportunity to do that. We settled on applying for the Fulbright because

it suited the kind of experience we were looking for. When I notified the editor

of the paper, and asked for a 1-year leave of absence, I had 100% intention

to return, she told me that there wasn’t anything she could do to insure my

job because the newspaper was up for sale at the time. She was incredibly

supportive about the opportunity, but thankfully was being honest and realistic

with me about the security of holding my job. Our plan to leave for a year

and come back to our lives totally went out the window at that moment.

Along the way, I began working with Truth With A Camera which is truly

one of the most amazing workshops I have been involved with. We’ve held

three workshops – in Mexico, Ecuador and Bosnia – and are planning the

next series. It’s all a bit strange to me, as I always thought that I’d be

working at a newspaper, loving my job and making pictures for my career,

but that has changed somewhat in these past few years. I also realize that

many photojournalists have not been fortunate enough to leave their

newspaper jobs on their own terms and have had to reinvent themselves

not on their own timelines, which I can only imagine must be stressful. So

I feel incredibly lucky to have chosen my own course, more or less.

But back to photography. The Fulbright year taught me a lot, about

working on my own and working on a long-term project, keeping it on track

and seeking guidance from others (which I needed to do more of). I left the

year with 4 terabytes of video and images that I have more or less done

nothing with. I plan to return to Mexico to finish the project as part of my

masters thesis and will seek publication opportunities then.

TID:

Were there challenges involved in making this story/picture happen?

JOSH:

Really it’s such straight forward image, but I talk about the preparation

in question #1 above. As for the story, I think there is a lot of racism in

Mexico by some of Spanish descent to those of indigenous descent.

Occasionally I would get a look of “why would you do that story” from

people I approached about the project, as if to say, “who cares about

them, they’re just beggars or dragging down Mexico.”

TID:

What advice do you have to other people who want to make this type of

image or do this kind of work?

JOSH:

Really I think it’s important to pursue projects that are important to you,

and ones that you feel can improve mutual understanding for whatever

community you’re working in. Too often we shoot stories because they’re

assigned to us, and complain that we don’t have interesting things to

shoot, but really, that’s a sign that you’re not finding your own material,

or you work in an entirely prohibitive environment for that kind of enterprise

journalism. Either way, you must make a change.

More importantly though, in current times, it’s important to be aware of the

number of grants and nontraditional opportunities to help fund and support

personal projects. New non-profits like Photophilanthropy are helping

photographers on a number of levels. They have grants, both for professionals

and students, and are working hard to help photojournalists partner with

NGOs to tell important stories in the non-profit world. Find organizations with

whom you want to align yourself and approach them with a proposal.

TID:

You said that this was an easy image to make technically, but the difficulty

was in putting yourself in the position to make the image. Can you please

talk about your mental approach to addressing this difficulty?

JOSH:

Yes, predicting images is clearly very important in making still images or

video that represents larger situations. What I'm about to say

doesn't pertain specifically to this image, but I think in general cases,

people watching is also a very big component of problem solving and

prediction in terms of visual storytelling.

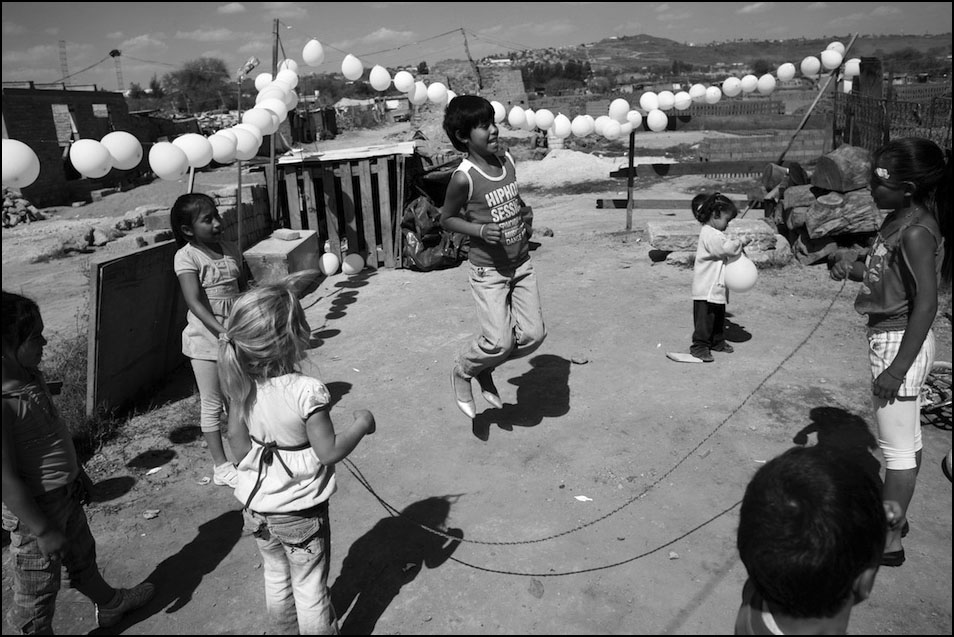

I spend a lot of time at events before I start to shoot just gaging the

situation, eyeing people up, listening to conversations and figuring out not

only might happen but who will be the best characters for whatever situation

or story I'm trying to tell. I do this by just walking around, chatting casually

with folks and getting a sense of who's who. We don't need to photograph

everything or everyone, but we do need images that represent a lot of what

is happening, and so if you look at the images featured on this blog, just for

starters, they do just that. They are images of individuals or small groups of

people who are representative of a larger issue or story.

Also, I think it's important to understand what the crux of the story is.

What is at the heart of it and who should be telling it, either audibly or

visually? There is mood to be considered, which is very much attached

to moment, and so having that key understanding of what

we're shooting is important. I've been on too many assignments

where I didn't clearly understand the topic and at those moments I wasn't

able to do my best, so doing research, planning, understanding, listening

and then just plain observing go a long way to making powerful images.

When you understand the story and its characters you're better armed

to make meaningful moment pictures.

TID:

OK now, onto the image. Please tell us what happened.

JOSH:

Well, I shot some of the family going through the fence on the way to the

baptism, but the light was from the wrong side and really nothing was working

for the image, but I shot a short sequence just to have a visual reminder for

the walk back to their home from church, because I knew the light would be

better. Of course, let's not forget that luck can certainly play a role in

photojournalism form time to time. For as much as I could plan and think,

luck allowed the girl to be sleeping and that kind of thing. Don't deny that it

exists....and of course bad luck exists just the same.

I'm not a big shooter as far as massive amount of images, perhaps because

I started by using film, which you had to change every 36 pictures but really

because I've missed the exact moment many times when I've actually shot

too many frames, not looking through the camera and not timing the press of

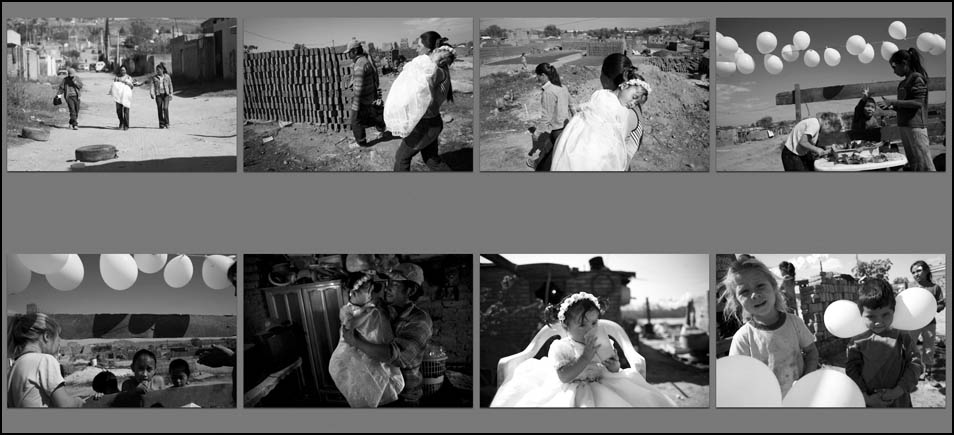

the shutter exactly. So as you can see, in this series on the way home, I only

shot 5 or so pictures, really knowing that a simple designed photo, very

centered, very symmetrical, would do the trick.

Also, I think this photo is a good example that making images before and after

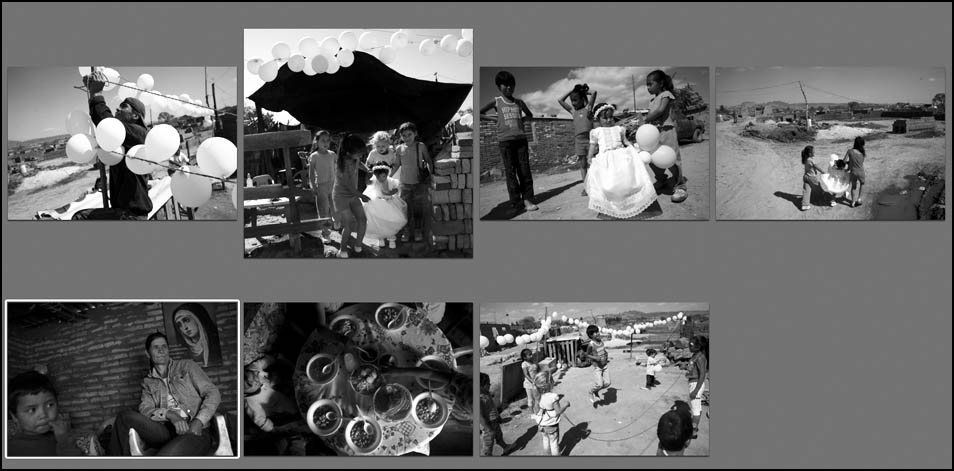

events is usually a better time to shoot than during the event itself. If I had to

do a very very loose edit from that day, let's say of my favorite 50 images,

maybe only the last 5 of those would have been from the event itself. I showed

up several hours early, and stayed the entire day during the family celebration,

as much for myself to shoot as to honor their day of festivities. I even tried pig

ear, a delicacy!! I've included some of the other images from that day.

But in the end, sometimes one picture is all you need to tell the story. It has

the contrast of the beautiful white dress to the father's drab work clothes.

The fence is both literal for where they live and symbolic for the larger project

in general, so perhaps this image can stand on its own. I counted that I went

over a dozen times to this little community, one of about six or seven that I

photographed during my year in Mexico, and for a final edit, I maybe only used

1-3 other images from this community in the final museum show in Guadalajara.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself in the process of making this image,

and in working on this project?

JOSH:

I now have a child of my own, who wasn't in the picture then. My wife and

I spent a bit of time going through these together recently and it really felt

different, now that we're raising our son Gus. Quality of life, happiness,

family, health and education are such different terms to me now, and as I

watch him grow, I can appreciate how different our lives are, and at the same

time how similar they are. Building bridges between communities that may

not on the surface have anything to do with one another, is exactly what we

can and should be doing with photojournalism and storytelling.

It is our challenge. How can we make middle class Americans or Chinese, or

Danish people care about the situation of a migrant family community outside

of a city in Mexico? It's easy - make it relatable. Show the similarities that

exist in both communities. For this, it could be family, tradition, religion,

faith, work ethic, parenting, or any number of things. If you focus only on the

differences of culture, then we aren't building that bridge.

Thanks so much for asking me to be a part of this blog. I'm a huge fan and

am quite humbled to be a part of it.

++++

In 2008, after 9 years as a staff photographer and multimedia journalist at The Roanoke Times in Roanoke, Virginia, Josh accepted a Fulbright Scholarship to work and teach in Mexico where he worked to create a multimedia project about the migration of indigenous families within Mexico. A selection of his work from his Fulbright year won the Grand Prize Professional Award from Photophilanthropy in 2010.

His still and multimedia work has been recognized by NPPA’s Best of Photojournalism competition, where he was the 2006 Photojournalist of the Year for markets less than 115,000 circulation, POYi, KNPA, VNPA, Atlanta Photojournalism Competition, Northern and Southern Short Courses and the Society of Newspaper Design.

Josh, his wife Missy and 1-year-old son Gus are living in Miami, FL through the end of 2012 while he is on leave from WKU to pursue a Masters degree at the University of Miami focusing on multimedia programming and design. His work can be found online at:

EDITOR'S NOTE - this week's interview was conducted by James Gregg,

a contributor to the blog. James Gregg is a staff photographer at the San

Diego Union-Tribune specializing in video and multimedia. He was the

2009 Photographer of the Year (Smaller Markets) in NPPA's Best of

Photojournalism competition.

You can view his work at:

www.jamesgreggphoto.com

++++

Next week we'll explore this lovely image by Kendrick Brinson of Luceo

from her Sun City project:

If you have any suggestions or if you want to interview someone

for the blog, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting: