Spotlight on John Tlumacki

Jan 5, 2014

EDITOR'S NOTE:

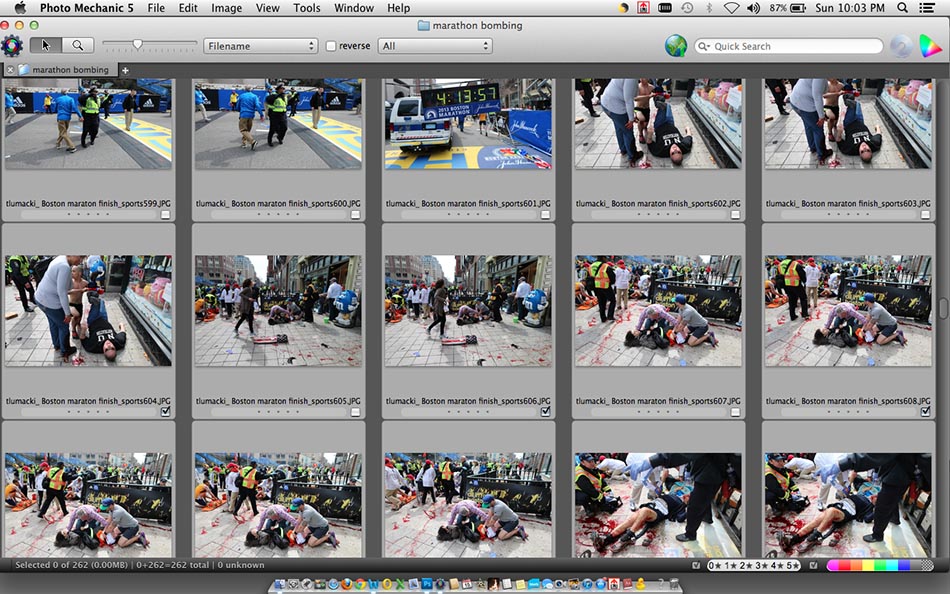

Unlike other Image Deconstructed examinations, this situation presented its iconic image first, followed with documentation over fewer than 15 minutes. Instead of exploring just one image, we will explore the situation as a whole.

TID:

The first thing you encounter after the first bomb detonates is runner Bill Iffrig on the ground with police officers in front of him, one with a pistol drawn. This image quickly turned into the iconic image from the marathon bombing when Sports Illustrated put it on its cover that day. It is the image with which we begin the deconstruction. Talk us through those few seconds you had photographing this moment.

JOHN:

This photo was taken within seconds after the first bomb exploded a little over 45 feet away from me. I was standing on the finish line on Boylston Street photographing different runners crossing the finish. I remember one of the last runners was a man who was holding the hands of children, and the announcer in the booth at the finish line would announce the names of certain runners. There was applause from the spectators that lined the sidewalk near the finish line. It was not unusual for me to still be shooting over two and a half hours after the winners already finished. I always made some of my best photos at that time — of runners dressed in costumes or crawling to the finish line. The average runners were running now, and most were raising money for different charities. When the bomb went off, I was jolted by the explosion to the point that my horizon was tilted in my photos. I looked to the right in the direction of the bomb and first thought that maybe a canon salute went off, or even a manhole cover exploded. At the same time I was running forward already, and saw Bill Iffrig on the ground as I ran toward him. I just kept shooting and the three Boston Police officers ran toward him and me as the second bomb exploded about three blocks away in the background. I just kept shooting and ran to the fence that was along the sidewalk.

I photographed police and Marathon workers trying to remove the fence and barriers, and shot a few “hail Mary” shots of the scene on the sidewalk as the smoke was clearing. One of the heroes, Carlos Arredondo, is seen jumping over the barricades and fence. I was looking for an opening in the fence to get on the sidewalk as a Boston Police officer looked at me and said, “You shouldn’t be here. Another bomb could go off.” That’s when I believe I understood the significance of what happened. I kept looking for an opening and found one to the right of the fence. Another officer said, “Please use some dignity when you are taking photos.” I don’t know if he knew I was from a newspaper. My thoughts were: get in there; make photos; you might get thrown out at any time. I was feeling anger that it might have been a bomb. I was also thinking that I might get thrown out real soon. I don’t think I had time to be scared. I knew that it was my responsibility to photograph as much as I could. I did not see any other photographers. Someone kept yelling, “Oh my God, oh my God,” and I saw that it was the Boston.com reporter shooting video. He was not experienced in shooting news events. That was the only screaming I heard. Otherwise it was strangely quiet.

TID:

No one can foresee something like this happening, let alone a mere 50 feet or so from where you stood. How are you doing eight months after having experienced and recorded this tragic crime?

JOHN:

Eight months later I still can see my images in my mind without having to look at the actual photographs. I feel I have control over it now. By control, I mean I can choose to think about the photos. Sometime I have to look at them, and all my outtakes, and that can be difficult, but not as difficult as it was in the first few weeks after it happened. I am proud of my work on that day and feel that the photographs have helped so many people, from the victims, to the first responders, to the reader of The Globe and wherever the photos ended up. I sometimes question myself as to whether I could have done a better job, or made it to the second bombsite. It is still difficult to go the Marathon finish. I was there about three times: once for CNN in April when they filmed me for a documentary, another for the Pride Parade, and the last time to scope out position for the Red Sox World Series parade.

The last time, in October, I stood there and visually placed all the victims in their places that I photographed. In April, a week after the marathon, I started building a backyard shed with my wife Debee, something I always wanted to do. It was finished in October, and probably was the third most therapeutic thing I have done; the second is talking about the Marathon; and the first is documenting the recovery of bombing victims Celeste Corcoran and her daughter Sydney. Celeste lost both her legs, and Sydney almost died from a severed artery in her leg.

TID:

What during your life do you think prepared you to cover this event?

JOHN:

Everything I learned in my career prepared me for this event. I have been exposed to death before covering fires, car accidents, stabbings, shootings; you name it. But there was always a distance between myself and victims. It’s not like you don’t get close to them, but as a photographer I guess you put up this mental, emotional barrier up to protect yourself from getting overwhelmed with all these experiences. During a house fire in the Dorchester section of Boston, working the overnight shift, I got there before the fire department and a woman ran from the house yelling at me that her children were inside. The flames were coming out the front door. I went onto the front porch but couldn’t get close. I told the arriving firefighters what she told me. The children died. I was in Kampala, Uganda, when my reporter and I were made to get out of our car by an armed youth who was high on drugs, and questioned us. A few packs of cigarettes later we were on our way, but I kept thinking that he was going to shoot through the back of the car as we left.

These kind of things season you as a photojournalist, but they never take the fear away from you. Behind all that camera gear, you are still person with emotions. That’s what mattered to me most, and that’s what made me make it through April 15, because I believe my emotions and compassion came across in the photos.

TID:

As you make your way over to where the first bomb went off, what were you learning and what were you considering — journalistically and practically — as you begin making pictures?

JOHN:

As I made my way over to where the first bomb off, I was looking through the camera most of the time except when I had to walk around the scene, back and forth. I kept thinking of the “dignity” the police officer said, but it was unavoidable to shoot photos that were horrific. I had faith in my new Canon camera, and my new 24mm 1.4 lens. Maybe it was the new technology of the [HD] quality and lens that brought out every detail in the photos compared to earlier years and camera versions, or even film. It was odd that nobody told me to leave, or stop shooting, even when I got onto the sidewalk. I did noticed how fast the response was with the Boston EMS and fire department as they were already working on victims along with family members and first responders. Time kept ticking in my head like a stopwatch wondering when I would be thrown out. I went out of the sidewalk area once, and then went back onto it again. Most of my photos were wide-angle, but I did shoot some telephoto with my 70-200 zoom. I didn’t ever look at the images on the display screen on my camera until I left the area.

TID:

Are there details that you remember and you’re unsure why? What stands out in your memory, and have any gaps in your memory of your time in the event begun to fill in?

JOHN:

I remember taking photos of a Boston Police officer standing near the bomb scene and looking up at a building where the glass was shattered, and thinking that this was interesting, was there a bomb inside the building that did this? I remember shooting the two American flags on the ground in front of Sydney Corcoran as she was being helped on the ground. There was so much blood right away — within 30 seconds of the first bomb is when I made it over to the fence, and the sidewalk was covered with it. I smelled the gunpowder smoke like the Fourth of July. A lot of things I didn’t really see until I edited my photos. I don’t remember seeing Jeff Bauman on the ground smoldering with his legs off. I do remember seeing and photographing a Boston policewoman putting the fingers in her purple medical gloves on the neck of Krystle Campbell who died. This is the most disturbing sequence of photos. What happened to her, I will not describe.

TID:

Walk us through the remainder of the time while you were on the scene and what your conscious decisions were to photograph the event in the way you did.

JOHN:

I made more photos of Sydney Corcoran, of Nicole Gross and first responders. I went back onto Boylston Street after about 10 minutes of shooting and shot some telephoto shots; one was of a marathon volunteer pumping Krystle Campbell’s chest. I then went to the finish line and shot victims being wheeled across the line in stretchers.

TID:

What stood out for you as a poignant moment as you were walking away from the finish line with your belongings heading back to The Globe newsroom?

JOHN:

One of the most poignant moments was of a woman I photographed who knelt on the ground about 100 feet past the finish line and cried and prayed while leaning on the barricade fence along the sidewalk. I don’t know who she was or if she knew anybody in the marathon, but she was a true angel to do what she did. I got a call at this point from my photo editor, Kim Chapin, who did not ask if I got “anything good,” but asked if I was all right. I then called my wife and told her I was OK.

TID:

Part of your work from that morning included images of radical amputations and massive amounts of blood on the Boylston Street sidewalk. Can you go through editing decisions to publish versus not publish graphic images in The Globe that day?

JOHN:

There were graphic images that I had to edit. When I returned to The Globe, I was allowed to edit my photos by myself. I went through every frame. I regret one frame that I put in of Krystle Campbell and the police officer touching her neck, but I cropped it enough and felt it was an important image. The photo of Nicole Gross struggling to get up and looking stunned, with Celeste Corcoran in the background being helped by her husband Kevin, was such an important photo to show. It spoke of terrorism. The Globe chose to publish on the front page the photo of Sydney Corcoran being helped by two bystanders who ultimately saved her life. The photo had blood, but it also showed compassion of first responders and part of the sidewalk scene. There are photos I shot that will never see the light of day. I see them when I need to see who was where.

TID:

You’ve since met many people whom you had photographed that morning. How has that helped both you and them in dealing with experiences from, and after, the marathon?

JOHN:

Two remarkable stories emerge after my coverage. Nicole Gross’ family sent out an email to news organizations and asked that the photo I took of her not be used because it is disturbing to her and the family. But a week later, I get a phone call from her mother-in-law that Nicole would like to meet me. I meet her the day before she leaves Spaulding Rehab Hospital in Boston, and we hugged and cried. I apologized for the photo but she thanked me for taking it, and said it did more than anything to put a face on the victims of terrorism and to raise money for the victims. I gave her my Marathon credential. I also met her sister, Erika Brannock, who lost her leg, at her hospital before she left Boston. She told me about a woman who helped her and comforted her, whom she was trying to find. I looked through my outtakes and was able to find a photo, which CNN broadcast on the Anderson Cooper show.

Viewers identified the woman through the photo, and CNN reunited them. I met Celeste and Sydney Corcoran at Spaulding Hospital two weeks after the bombing. I hugged Sydney and her mother Celeste in their wheelchairs as they sat side by side. The first thing I did was ask Sydney if I could take a photo of her, because I didn’t want to remember her by the photos I took of her at the Marathon. I said I was sorry for taking the photos of them and felt guilty for leaving them that day, and Celeste said to me, “John, if there was nobody helping Sydney, I know you would [have] put your cameras down and helped her.” I made a commitment with them that I would document their recovery for the rest of the year, which I am still doing, the story to be published before Christmas. They have welcomed me into their family. They have been so open. The most amazing blessing is to hug two people, Celeste and Sydney, each time I see them — two people that I left that day, not knowing if they had lived or died. I met two of the Boston Police officers in the iconic photo at a Pride Parade in August. I introduced myself, and we hugged one another. It’s not often in your career that you can do this, but I feel that we are all connected to this tragedy.

TID:

What symptoms do you continue to experience from the marathon bombing? What has been your plan to work through these symptoms and be able to minimize their impact to live life?

JOHN:

I had some difficultly sleeping for the first weeks after the Marathon. Images kept playing in my head, over and over and over, but as time went by, they became less. I went with my wife to Sedona, Ariz., in late November for a week, and I embraced the beauty of the place and photographed it, not because I had to, but because I wanted to. I wanted to move these beautiful photographs into my mind and let them take over my dreams. I believe it worked really well. I don’t want to forget what I saw on Marathon day, but I want to control those images in my mind and not get overwhelmed with them. I would seek PTSD help if I thought I needed it, but [I] feel good right now. The Globe offered it to me in the days following the Marathon, and even a Boston Police officer said I could go to the 415 PTSD program at Spaulding. My wife is my barometer, and she would be the first one to recognize my need for help.

TID:

What education would you benefit from regarding how mental trauma can impact your life and/or have you sought a therapist with whom to work through your experience?

JOHN:

I have never been to a therapist, except to photograph them. I feel in control and would seek help if I need it. Just by listening to Celeste talk sometimes is like listening to Ghandi, which to me is priceless.

TID:

What would you tell someone who may have to cover an event such as this and deal with its effects afterward?

JOHN:

I would say that photojournalists who ever have to cover such an event should not try to hide their emotions. They should be compassionate, show dignity and try to give back when it’s all over. For me, the story did not end that day on Boylston Street. I felt guilty leaving all those people, and the way I can give back is to show the courage that they have to become “normal” again, or as Celeste calls it, “my new normal." By all means, talk about what happened to your family, coworkers, and doing media interviews if requested. All the dozens of interviews that I did have meant so much to me and gave me a chance not to talk about myself, but to talk about the recovery of the victims I have met.

TID:

What haven’t you discussed during all of the interviews you’ve done that you feel is important to discuss in the public forum?

JOHN:

Whatever you do, do it from the heart. People need to trust you in this day of quick, cheap iPhone photos and video. Don’t betray your trust. The camera may be your security blanket in dangerous situations, but be smart and trust your instincts. Don’t be foolish.

Also, you have to be so confident in your equipment. What I hold dear to me is the memory I have of being able to leave my Marathon photographer’s bib in front of the cross made for Krystal Campbell at a makeshift memorial, two streets away from the finish line, on the Friday when Boston was shut down as police hunted down the terrorists.

I was assigned to photograph the Red Sox in the World Series, being stationed in center field of Fenway Park. There was a large ‘B Strong’ carved in the grass of centerfield. When the Sox won the Series, a ceremony took place at second base, and as it began, fireworks went off behind me on the roof of a parking garage. They startled me at first because I wasn’t expecting them. Fenway was filled with smoke, and when it slowly started to clear, I made one of my favorite photos showing ‘B Strong’ surrounded by the smoke. The last time I heard and saw something similar was on April 15th. This was a happy ending, to say the least.

Epilogue

So after nearly eight months of documenting the recovery of Boston Marathon survivors Celeste Corcoran and her daughter Sydney, the publication day was set for December 29th in the Boston Sunday Globe. I spent hours during the last days editing a video that I was reluctant to shoot at first, thinking that it might not sit well with the family. I realized as their recovery progressed that what Celeste and Sydney had to say was so profound that I started to shoot video.

In the moments that were so emotional for them, they were able to speak their mind and trusted me with what I was doing. I felt their story needed to be told in an intimate way that TV could not do. So as summer progressed into fall, it seemed that the photos that I took were far and few between, but the videos got stronger, as the interviews were not really interviews but more like a conversation with me as a friend. Sydney was able to speak her mind like her mother. They both had so much to say and almost needed to get it out. There again, I felt so much responsibility to tell their story and for them to be comfortable with it.

Sunday came and as usual, I went down our driveway and got the paper. On the front page was a photo of Celeste and Sydney taken in May when Celeste was learning to stand up for the first time, and she said to Sydney, “This is so hard.” The paper had a three-page spread of photos, and the story written by Globe reporter Kay Lazar was like reliving every moment. I got a text from Celeste’s husband, Kevin, at 8 a.m. that said he was on the way out to buy the paper. Then Celeste called an hour later and said she was about to look at the gallery of 35 photos online and the video. She said she would get back to me.

I was never was so anxious to hear anyone’s reaction to the work that I have done. I wanted to know if she was happy with it. Hours went by. I kept looking at my iPhone — maybe she would text or email me instead. The phone rang right around 3 p.m. and it was Celeste. She was so thankful, so appreciative (big sigh), so emotional. We talked for nearly half an hour, and she told me that she never expected the story to be just on her and her family. She said the video was amazing. They were very comforting words, but in a way what she said next brought closure to me for the guilt I have been holding inside of me for photographing her and Sydney the way I did after the bombing. She said in a stern voice, “I don’t ever want you to feel guilt for taking the photos you did. You were doing your job, and if it wasn’t for you, the world wouldn’t have seen what terrorism had done to us and everyone else!”

I felt immediately absolved. Sydney texted me that she loved what Kay and I had done, and said it was moving. I’m so glad. That’s all I can say. I move on from here. Celeste is going to be fitted in January for running legs and train at home in a gym. We will be in touch. She is determined to run across the Boston Marathon finish line in 2014, one way or another. She will not run the whole race, but maybe the last mile. And she will be holding hands with her daughter Sydney, and her sister, Carmen, whom she went to watch finish in the 2013 Boston Marathon. And I will be there in my usual position at the finish line.

EDITOR'S NOTE:

This week's interview was done by Rich Glickstein. Glickstein is a photojournalist-turned-addiction and trauma therapist. He left The State newspaper in Columbia, S.C., after 10 years to complete a graduate degree in social work and specialize in trauma therapy for combat-experienced service members and journalists. He has worked at an in-patient detox unit in Atlanta and at the Army Substance Abuse Program at Fort Gordon, Ga. He is now a therapist working with veterans at Talbott Recovery Campus in Dunwoody, Ga. He lives in Atlanta with his wife.

:::BIO:::

John Tlumacki is a staff photographer for the Boston Globe, where he has worked since 1981. Tlumacki has covered the Boston Marathon more than 20 times. The 2013 Marathon was his fifth year in a row shooting in the pool position at ground level at the finish line. Tlumacki was standing at the finish line when the first explosion happened.

Tlumacki was named the Boston Press Photographer of the Year for 2011. He was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. He won Second Place NPPA — Newspaper Photographer of the Year in the Picture of the Year Competition in 1987. Tlumacki is a general assignment photographer and lives with his wife Debee, who is also a news photographer, in Pembroke, Mass.