Spotlight on James Gregg

Nov 4, 2012

TID:

This is a very powerful image, within a very powerful story. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

JAMES:

I was assigned to be part of this project in a partnership with the California Center for Health Reporting. The center made a proposal to the newspaper to do an investigative series on frequent use of the emergency system and its impact on taxpayers, as well as city and hospital resources. They would contribute the reporter and a project editor and partner with us as a publishing platform. The paper really wanted to have some skin in the game with a photojournalist and asked me to take it on, in no small part to their desire to include video in the project. I've been working with a lot of video for the past two years and they felt I could handle that in addition to still photography.

TID:

How did you prepare for this project, or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

JAMES:

I made a lot of mistakes. This was an investigative story, so a lot of the things we were documenting for the story we were seeing for the first time and wouldn't see them again. In the beginning, I did a lot of shooting video and stills at the same time. Anyone who has tried that knows how hard it can be, and often you end up getting mediocre results from both. I worked closely with reporter John Gonzales, who used to be a staffer with the Associated Press. We were in constant communication about where the story was going and which subjects we were drawn to.

In any collaboration with a writing colleague, some of the time we were focusing on the same people and details, and sometimes we would go in separate directions linked by an overall message. As the bigger picture took shape, I was more able to focus when I would shoot stills or when I would shoot video. Eventually, I started to pick one or the other so on a particular day, I could focus on getting excellent results from each with less distraction. I would always take an audio recorder when shooting stills.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

JAMES:

I had been working on the project for about a month when the emergency room photo was made. I had already been working on editing and had been largely unsatisfied with what stills I had from the ER, so I made an arrangement to go back to the ER alone to focus on that. Until then, we had to be accompanied by hospital PR folks or by one of our main subjects, Dr. James Dunford, who vouched for us as we embedded with him. I had been there for a couple of shifts already and spent a lot of time relationship-building with the ER staff and the PR department. They knew why I was there and had seen me work. They trusted that I would work with dignity and respect, as well as take extensive care in HIPAA privacy concerns. That credibility proved invaluable in getting the access I needed to make images with impact in a very sensitive environment. It even got to the point where if I was on a scene where someone was picked up by ambulance, I could jump on the rig and make a phone call that I was going to be in the ER within minutes, and they would let me come in. That's not possible without a relationship being established ahead of time.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

JAMES:

After sticking to Dr. Dunford's hip for most of my first visits to the Emergency Department, people eventually started to get to know me and see for themselves that I could be trusted. No one wants to follow a photographer around for hours at a time; they have better things to do, especially in a busy ER. They just needed to know that if I was off site, they knew where I was and that I was checking back with them about who I was photographing. It was quite a helpful relationship for me as well, as nursing staff was willing to talk with patients about what I was doing and ask permission to be photographed. In some cases, the situations were important for the story and needed to be photographed in ways that protected a patient's identity. I was very careful to keep from showing faces of people who had not given me their consent.

TID:

You said this was part of an investigative piece. Did you feel additional pressure to dig deeper due to the nature of the report? If so, can you speak to this (how this may differ from daily work mentally)?

JAMES:

Working on this project was certainly a lot more in depth than my daily work. There are a lot of factors that go into putting together a series that is investigative in nature, and there is a lot more to be done than to just make pictures. In fact, image making was a very small part of the time that it took to put this together. At every step, I'm following up on information that we have already gathered, looking for ways to tell those aspects of the story, but I'm also learning and discovering as we go. You really have to be thoughtful and constantly questioning yourself about what you are witnessing and how it fits into the big picture.

I'm constantly interviewing people and collaborating with my writing partner, and consider myself to be an important information source for him as well. What is written reflects me just as much as the writer so I spend a lot of time doing the journalism part, especially because there was so much video involved. A lot of the video interviews that I did ended up in the written series. There is really no way to have a set plan, and you have to be adaptable. The pressure that I felt was to be accurate in what I was portraying with my reporting. This is an extremely vulnerable group of people, and I lost a lot of sleep trying to ensure that I was treating them fairly.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

JAMES:

When I think of that particular instance, and for the entire project as a whole, I am reminded of the responsibility of dealing with sensitive subject matter. I kept reminding myself over and over that these are real people, and they deserve dignity. Despite the opportunity to make dramatic images, I wanted to simply receive what was in front of me and represent it for what it was. I really wanted to be a window into a world that many would not otherwise have seen.

TID:

What have you learned about others?

JAMES:

I think that most people want their story to be told, and in an honest and genuine way. If they feel that you are coming from that perspective, more often than not, they will show you themselves.

TID:

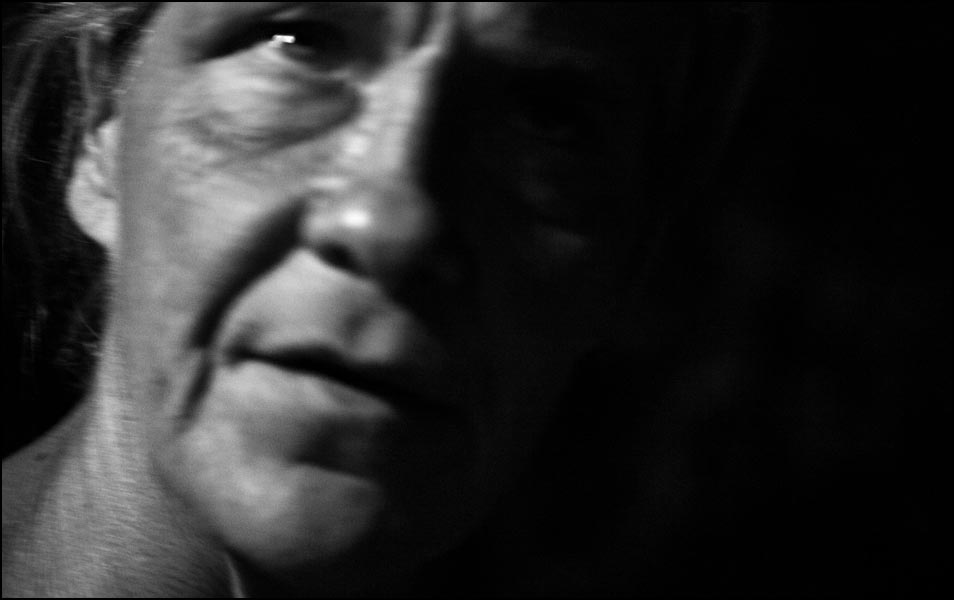

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

JAMES:

That night I was in the hospital to make pictures of a couple of specific things. I had been working with some specific cases studies of individual patients. Missing though, was the impact on the ER itself, so I was looking for pictures that would show the volume and intensity of the situations that I had been hearing about, one of which was the staff feeling threatened by patients who would act out violently. Screaming profanities or even striking at ER staff were things that I had interviewed people about. The frustration, fear, and distraction that it causes medical professionals and the patients themselves was key to showing why this was a problem. When this man came in, he was shouting profanities and thrashing in his gurney, and the ambulance crew reported that he had to tie him down to keep him from punching and kicking them. It was an unsettling scene for the staff, other patients and for me. I wanted to make a picture that could represent the situation not just in the case of this patient, but for all of the other times that I had heard about.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

JAMES:

I guess what surprised me is about how empty it seemed. Once the man was taken to a room he continued to struggle and shout out, but it was like there was no one around for miles, just me, standing in the doorway. I was affected by how this man could be so alone and in such turmoil. It didn't seem right that he should have to be in so much pain and struggle with it all by himself. I took very few frames and despite the shouting and the sounds of the ER behind me, it felt like such a quite moment. The staff treated him professionally and appropriately, but for those few minutes before the doctor arrived, it seemed like he was all alone in the world.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

JAMES:

Let relationships carry your efforts as a visual journalist. If you put your energy into understanding people and issues, and treat the opportunity to witness them as precious, then the pictures will come. It is a responsibility to be given that gift, make the most of it. People are counting on you to get it right.

:::BIO:::

James Gregg got his start at a Spanish language weekly newspaper in northern Colorado after graduating with a degree in Latin American Studies from the University of Kansas. He has also worked at the Arizona Daily Star in Tucson, and most recently joined the staff of the San Diego Union-Tribune. James has worked extensively on immigration and border issues, including security efforts, community advocacy, and human and drug trafficking. He was named NPPA’s Best of Photojournalism Photographer of the Year (Smaller Markets) in 2009 after finishing second the year before and was a finalist for Arizona POY three times, winning twice. While in Tucson, James started learning multimedia storytelling and now carries that as a specialty in San Diego in addition to still photography and does a weekly television segment on mixed martial arts.

James’ multimedia work has earned five regional Emmy Awards and was recognized with a third place multimedia portfolio from Pictures of the Year International in 2012 in addition to individual awards in POYi and NPPA’s Best of Photojournalism. The Healh Care 911 project was made into The Union-Tribune's first Ipad book, which can be downloaded for free here.

You can view more of his work here: