Spotlight On Erika Schultz

Oct 15, 2011

(editor's note - all images in this interview are

under the copyright of The Seattle Times)

TID:

Erika, thanks for taking the time to speak with us. Please

tell us a little bit about the background of this week's

featured image:

ERIKA:

Ross, thanks so much for creating The Image, Deconstructed.

It’s an inspiring and valuable resource for the photojournalism

community.

Kim moved her two sons— including Jack, 9— from Chicago

to Seattle in April 2010 after looking for work for about a year.

Kim had heard there were good job opportunities in the

Northwest. But the housing vouchers she had been counting

on never materialized. They soon moved into a tent city called

Nickelsville, and tried to establish their lives in a new city with

very little.

This photograph of Jack was taken as he moved from the tent

city into the room his family was renting in the University District.

After weeks of living without running water or electricity, Jack and

Kim finally had a room of their own, and a kitchen and bathroom

to share with other residents on their floor.

The photo essay about Kim and Jack’s journey published in The

Seattle Times in August 2010 as part of the final installment in a

three-day, multiplatform series called “Invisible Families.”

You can see the gallery: http://bit.ly/mPtrV9

The Invisible Families project page: http://bit.ly/affjhJ

After meeting Kim and Jack at Nickelsville tent city, I soon

realized they had a strong relationship. They constantly joked

with one another and were very affectionate. Kim was warm,

open and funny. Jack was curious, imaginative and gregarious.

During their time at Nickelsville, she worried about providing

Jack a normal childhood through this difficult transition.

They spent the majority of their money moving across the

country. Some evenings, dinner was made over a campfire.

Taking a shower sometimes meant walking a couple miles

to a community center.

(Jack and Kim share a moment while living in the tent city. Kim read

online that jobs would open up in Seattle at the end of the recession.

Without lining up a job, she moved to Seattle hoping to find secretarial

work and a fresh start.)

I wanted to try to share a realistic and personal glimpse into a

family that was trying to maintain a sense of normalcy while

homeless. I also wanted to show their relationship and humor as well

as their quirks — like Jack’s love for the paranormal and his ability

to enlist other tent city residents to look for worms.

TID: Since this image is part of a larger story, please talk about

that story, and how this image fits in within the story.

ERIKA:

Reporter Lornet Turnbull and I started working on the project in the

spring of 2010 and it published at the end of that summer. Journalists

from within our community, including The Seattle Times, produced

stories about family homelessness as part of a fellowship

administered through Seattle University and funded by the Bill &

Melinda Gates Foundation.

The foundation said it sponsored the fellowship to focus attention

on homeless families, which are the fastest-growing, yet least visible

segment of the homeless population, both in Washington state and

nationally. It did not stipulate how fellows should pursue their work,

nor did it review what the fellows produced. Each fellow was granted

a $15,000 stipend. The Times used its stipend in part to enable a

staff member to serve as project manager of contributions from the

paper's online news partners. Our director of photography approached

me to work on the project after The Times received the fellowship.

While working on the project, Lornet and I talked to dozens of

organizations, caseworkers and families, both gathering information

together and separately. For weeks, we returned to shelters and

social-service organizations in search families who could share their stories.

I kept coming back to Nickelsville because I heard it was the only

tent city in the area that accepted families.

(Kim kisses Jack inside their tent during bedtime at Nickelsville.

"Our nighttime ritual is goodnight, I love you," she said. She made

their sleeping area out of a feather bed, couch cushions and more

than a dozen moving quilts.)

I met Kim and Jack while they were working at the tent city’s security

desk. Kim told me a little of their story, and I let them know about our

project and some the parameters it would include. After parting ways,

I was both hopeful and nervous. I thought they had a good story, and

hoped they would be open to sharing it.

Soon after our conversation, Kim agreed to be a part the project. We

discussed the importance of capturing candid images that could

communicate both big and small moments in their lives.

Kim really embraced it. She let me know when they were

taking showers at the community center, doing laundry at The Urban

Rest Stop and later when they were looking for apartments. I still find

it amazing how well she kept in touch, despite all of their stress and

hardship.

(With his flashlight and family dog close by, Jack plays with his toy

plane before falling asleep in his tent at Nickelsville. He wears

“Transformers” and “Star Wars” pajamas.)

After we first met, they stayed in Nickeleville for about two weeks before

Kim found several agencies to help them secure a deposit and first

month’s rent for a room in the University District.

When the big day came for them to move, I knew when it was happening

and that I was invited to be there. Because we had developed trust and

understanding, I knew I could focus on the moments of the day through

photographs.

(The day of the move, Jack marches through Nickelsville with a

bamboo stick given to him by a fellow resident.)

TID:

Ok, now onto the image itself. Tell us what led up to the moment

at hand, and also what was going on while you made the image.

ERIKA:

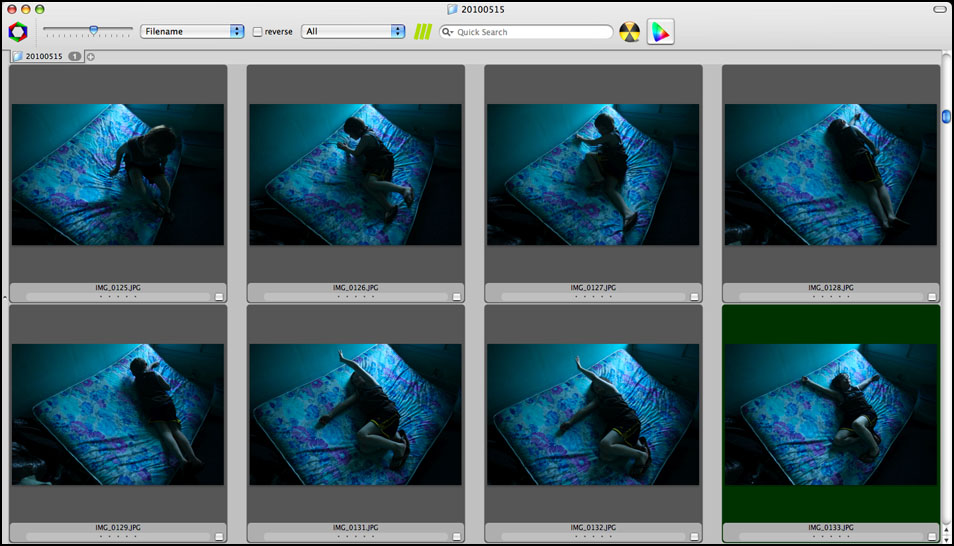

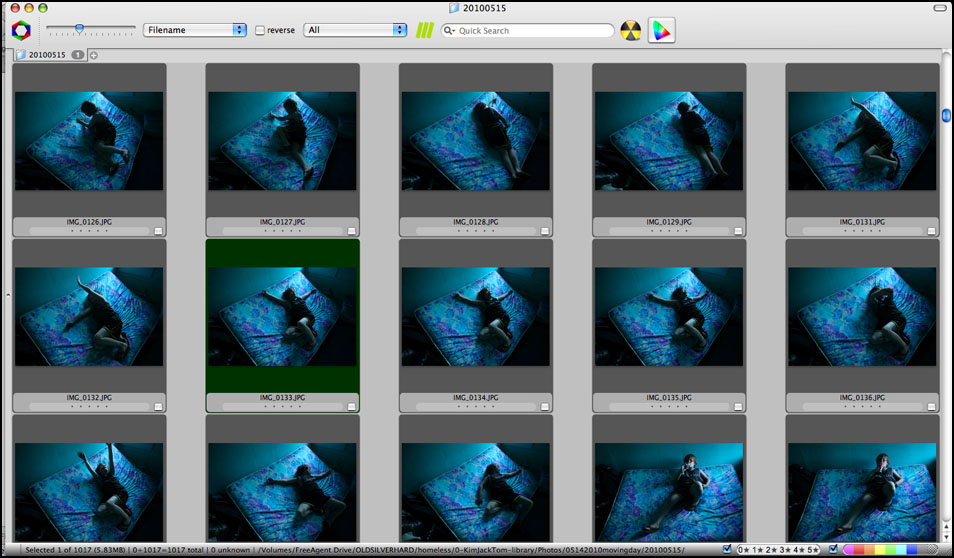

This image of Jack was taken while they were moving from Nickelsville

in South Seattle to their rented room in the University District.

Once their bed was brought up a long staircase and into their room,

Jack immediately jumped on the bed. He wriggled around for a bit,

stretched out for a few moments (This is when I took the photograph)

and then reached for a soda. We talked about how he was feeling in

the new place. He played with a bamboo stick and his dog, Gracie.

Then he returned to moving.

Early on, while working with Jack, I realized that sometimes I could be

a fly on the wall. But other times, he wanted to talk and interact. Did

you see that spider? Guess what my brother is doing? Can I play with

your camera? Do you know there are werewolves hiding in the bushes?

I sometimes photographed Jack during these conversations. I'm not

a fly on the wall when I photograph people. I want to listen to Jack's

frustrations and achievements. Have lunch with him. Tag along when he

looks for worms and bugs. Photograph him as his mom tucks him in for the night.

I feel the more time you spend with people the better. It helps develop

a better understanding of who they are, and more times than not,

it can lead to a photograph.

TID:

Was there any point of conflict during the making of this picture, or

during the story, and if so, how did you manage it?

ERIKA:

Homelessness and poverty are complex topics. I think one of the

challenges our reporter, editors and some of the multimedia storytellers

faced with the project was to how to share multiple perspectives of

homelessness.

(Most of their goods were stored in bags when moving. Kim, Jack, their friends

and Jack’s older brother Tom — who was around for only part of the time

during the story — took turns hauling up clothes and other items.)

Through a variety of mediums we tried to touch on issues involving a

lack of affordable housing in our region, the plight of refugee families,

single fathers, the working poor, programs in schools and workings of

the homeless support system. Even though we covered a lot of ground,

I think it’s challenging to concisely package the causes and solutions of

family homelessness in a three-day series. I think it takes continued

coverage.

While working with other families in the series (not with Kim and Jack)

I learned that homeless parents sometimes grapple with a variety of

issues. They can be stressed, scared, depressed and have drama in their

lives. Sometimes they don’t take opportunities to help themselves.

Sometimes they may not know all of the resources available.

And not all of their decisions make sense to someone outside their

situation. At times, I wondered if one family was telling the truth. It was

difficult to keep track of another. Other families had histories of substance

abuse. At points, I received phone calls and texts during all hours of the

day and night. So, I often leaned on my colleagues and editors to help

me to navigate these interactions. My purpose is to be with families as

a journalist, not a social worker. So during parts of the project I struggled

with guilt and frustration because I hadn’t been in some of these situations

before.

There were a lot of considerations while working on Kim and Jack’s story,

as well as other families' featured in the series.

We realized that caseworkers are sometimes protective of their clients,

because the families may be stressed or dealing with trauma. They may

want to refer you to a family who was previously homeless, versus a family

who is currently homeless.

Some parents feel fine discussing their struggles. But if their child or

one of the siblings does not want their friends to know at school, we

then knew they shouldn’t be involved in the project.

Other families may not want to be labeled as homeless. One of our

families in the series had second thoughts because they were nervous

about being the public face of homelessness. They were embarrassed

about their situation. They saw it as only temporary.

How much help we could provide to families while reporting

was also another important consideration.

Is it okay to purchase a meal for a family? Should we tell a family

about service providers that could help them in their area? Would

it alter the course of a family’s path by sharing certain resources?

Can we intervene in a story if a family is looking for a safe place to

spend the night? Can we help them after the story publishes?

(One of the first things Jack finds at their University District

apartment is a spider. Jack is seen through a small window

next to the front door. "They [the bugs] are amazing," Jack said.)

TID:

Was there any concern about you taking this picture at the

time, and if so, how did you handle it? (You mentioned the concept

of photographing children.)

ERIKA:

While working on this project, we realized that kids would

likely be placed in the most sensitive position during our coverage.

With some of the families, we discussed scenarios that could occur

after the story published. We listened to their concerns, and tried to

address those issues the best we could before starting to work with them.

(Kim takes a break while moving into her new apartment with her dog Gracie.)

There were a handful of families who decided they didn’t want to

be a part of the project after learning more about it. We acknowledged

that school aged children could be teased by their peers after the

story published.

But we also discussed possible positive outcomes of sharing

their stories. Media coverage can increase the public’s awareness

of family homelessness, encourage community dialog and possibly

help others in a similar situation.

After the project published, I learned one of the families wished to have

their last names removed from the online stories. Overall, they had a good

experience with the project. But they didn't want the names to always

be linked to story and to the fact they were homelessness during one point in their life.

One of the effects of online reporting is that subjects with sensitive stories

may be linked to these articles for perpetuity.

TID:

What lessons did you learn from making this image?

ERIKA:

I think this photo was created more by relationships than by

mechanics. Over a period of a couple weeks, Kim, Jack and I

had spent a lot of time together. By moving day, they both

seemed to be unguarded and open to my presence in their

lives. But I think our relationship worked twofold. Because

we developed trust, I felt like I could work without any major

insecurities or doubts. I felt like I had permission, a purpose

and an understanding of who they were.

TID:

What lessons did you learn from the overall story, and with this,

how did you change during this experience?

ERIKA:

As of last year, I worked at The Seattle Times for about four

years, which isn’t all that long as a professional journalist.

Through this project, I learned to have more trust in my voice

and ideas as a storyteller, but also to rely on the support and

experience of my editors and colleagues. I believe that because

we worked together, and told stories through a wide variety of

mediums in print and online, we were able to give depth and

multiple perspectives to a very complex problem. I think there

is a lot of power in collaboration.

I also think my love for community journalism, and my belief in

the power of it, grew after this project.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice (think mentally) do you have for

photographers to gain access to these type of situations?

ERIKA:

It’s important for photographers to be active in the reporting

and researching process. Photographers should initiate meetings

with sources and compile their own research while working with

a reporter. By being proactive as a visual storyteller, you can

put yourself on the path to telling more informed and visual stories.

Through this process, I’ve learned stories will inevitably fall through

and hit snags. It happened frequently during the series. But it’s

important to try to keep positive and realize that better stories and

situations will come if you keep searching.

Often the most difficult work wasn’t taking the photographs, but

putting myself in the physical or mental space to make them. I learned

it’s important to trust my instincts about people. Try to set boundaries.

And, in hindsight, I realized it’s good to take mental breaks from the

project.

Also, I think it’s important to have a conversation with the subjects

in your stories about what it would be like for them to take part in a

documentary project. I think it’s helpful to let them know the purpose

of the story, how much time you’d like spend time with them, when

you’d like to spend time with them, where you’d like to see the photos

published (web or in print) and the possible outcomes/reactions to the

story.

And I think it’s super valuable to bounce off ideas and share images

with an editor and peers you trust while working on a project. During

difficult days, I often got strength and rejuvenation from my colleagues,

which I am extremely grateful for.

A year later, Kim and Jack are doing really well. Kim found full-time

work and Jack’s elementary school is helping him both academically

and emotionally. They found permanent housing.

+++++

You can view the multimedia project, edited by Danny Gawlowski:

http://bcove.me/j8mdn64h

BIO

Erika Schultz was born and raised in central Wyoming. She attended college at Northern Arizona University, and works as a Seattle Times staff photographer. She loves the American West, Spanglish, well told tales and to travel.

Her work has been recognized by the Casey Medals for Meritorious Journalism, National Edward R. Murrow Awards, The Alexia Foundation for World Peace, Society of Professional Journalists and was a finalist for the 2010 ASNE Community Service Photojournalism award. She also was part of The Seattle Times’ 2010 Pulitzer Prize winning team for Breaking News Reporting.

Invisible Families:

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/flatpages/local/invisiblefamilies.html

You can view more of her work here:

http://www.erikajschultz.com/blog/

+++++

Next week we'll feature this surprising image by Gerry McCarthy:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

[email protected]

[email protected]

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/