Spotlight on Eric Kruszewski

Nov 17, 2015

Bobby Curran - Life after the Steel Mill in Maryland - Eric Kruszewski from Eric Kruszewski on Vimeo.

TID: Thanks for sharing your experiences with this project Eric. How did you find the story and why did you decide to pursue it as a personal project?

Eric: Thank you for the opportunity to share thoughts about the creative process with TID. My parents usually watch the daily news during dinner. One evening in late 2012, I joined them and let my attention bounce between our conversation and the local news. I recall a news clip that lasted about 30 seconds; the reporter mentioned that Sparrows Point Steel Mill, a manufacturing facility located in southeast Baltimore, had officially filed for bankruptcy and permanently closed its doors. At the time of closure, nearly two thousand people lost their employment.

For almost 125 years, Maryland was an industrial hub for steel making, and Sparrows Point (known as “The Point”), consisted of a tight-knit community that produced steel for iconic structures such as The Golden Gate Bridge. At its peak, The Point employed nearly 55,000 people. But in its last decade, the number of employees dwindled as a combination of technological and fiscal factors forced The Point’s slow decline into bankruptcy. With such rich history, I was shocked the media gave its death a mere half-minute. I remember saying to my parents, “Two thousand jobs lost. Immediately, here are two thousand stories of transition. I wonder what is going to happen to all of those people?”

The story hit home to me for two reasons: My mother’s family grew up near The Point, and her father was a blue-collar industrial man. In addition, I had recently made a huge transition in life - after 10 years in engineering, I changed careers to become a photographer. Therefore, I am interested in other peoples’ stories of transition. Suddenly, I felt compelled to meet the folks affected by the closure and document their evolution.

TID: How did you meet Bobby Curran?

Eric: When I heard about The Point’s closure, I was living with my parents, a 45-minute drive from the industrial area, and I didn’t know anyone that worked at the mill. I knew that for me to meet the right people, I had to go where they spent time. So over the next few weeks, I began doing research on the establishments around The Point. I searched the Internet with phrases like “Sparrows Point restaurants,” “Baltimore steel worker hangouts,” and “Dundalk, Maryland hot spots.” With each new result, I made a list of the places, along with their addresses and phone numbers. With Google maps, I plugged in each address and created a route for my pending exploration.

After finishing research, my final list included the following: local bars/restaurants, hair salons, barber shops, a flea market, sandwich shops, a strip club, a bingo hall and the steelworkers’ union hall. These were all places where folks are social, and just as importantly, people talk.

In mid-January 2013, I completed my research and drove from home to follow my map around The Point. I carried a camera, notepad, pen and business cards. As I reached each place on my list, I would ask for the owner or manager of the establishment. With each meeting, I would shake a hand and go through my premeditated introduction, “Hi, my name is Eric Kruszewski, and I’m a freelance photojournalist in Baltimore. I do work for editorial clients like The New York Times and Wall Street Journal. Recently, I learned of The Point’s closure. The news was shocking, and it really hit home because my family grew up in the area. I am interested in talking with people who have been deeply affected by this change and would like to tell their stories of transition. Would you happen to know anyone, a family member, friend, or perhaps customer, who might have mentioned something?”

When first introducing myself, it was imperative to be genuine and honest. As a photojournalist, I tell peoples’ stories, and that is a precious thing. Nobody will open his/her life and heart to someone who is misleading or not trustworthy.

At the first hair salon, sandwich shop, flea market and strip club, the people I met could not think of anyone. I was a bit discouraged, but I continued with my list. The next place was a local bar named Pop’s Tavern, a long-standing, family-run neighborhood joint. It was located on the main road that led into the steel mill, and it was the first bar that steelworkers would see upon exiting their workplace. In other words, it was the go-to place.

I went in and introduced myself to the owners (three generations of the family were there). I delivered my standard introduction, and everyone warmly welcomed me. They looked around the bar, and mentioned that it was a bit early for folks to arrive. It was around 4PM when I had entered the tavern, and the bartender told me, ”If you want to hang out for a few hours, tonight is card night, and I’m confident a few steelworkers will be here.” With that in mind, I bellied up to the bar, made myself comfortable and ordered a drink.

Hours later the tavern came to life. As patrons entered, I asked the bartender if he could point out specific folks with whom I could speak. At one point, while delivering food and beverages to a table, he glanced back at me and motioned a woman in my direction. She approached and said, “So I hear you’re looking for a story from The Point. I know a guy. Hang tight, hon, I gotta go to the bathroom, but I’ll be right back.”

Moments later, she emerged from the restroom. As she dried her hands with paper towels, she cradled her cell phone between her ear and shoulder. She grabbed the phone, thrust it towards me and said, “Here, talk to Bobby.”

That’s how I met Bobby Curran.

TID: How did you manage the connection and to gain access to his life and home?

Eric: Bobby and I spoke on the phone for only a few minutes. I told him who I was and what I wanted to do. He told me that he had lost his job due to the plant’s closure and planned to enroll in community college. He was totally candid and honest, almost amazingly so with a total stranger. Through his voice, I could feel that he wore his heart on his sleeve. That feeling culminated when he abruptly offered to change out of his pajamas and drive to the tavern to meet me.

Ten minutes later, Bobby arrived. We talked openly for the next hour and sipped on screwdrivers. The conversation flowed naturally as we shared our mutual stories, but the focus was mostly on what he was thinking and feeling about starting college for the first time. Just as he was on the phone, he remained sincere. He told me that his first day of school was going to be in a week and he was nervous about the entire upcoming endeavor. I asked if I could meet him at his house and go with him to campus for his first day of class. He agreed.

Bobby had worked at Sparrows Point for 39 years before losing his job just two years shy of retirement. After finishing high school, Bobby had taken the path of instant employment at the mill – something his family and neighbors had done for decades before. So with the mill’s closure, Bobby was forced with a decision: find a new job or retrain with the assistance of a state and federally funded program. He had chosen the latter.

Bobby enrolled with a full course load – Algebra, English and two Sociology courses. The idea of lessons, homework and associated deadlines were things absent from his life for the last four decades. I wanted to capture what it would be like for a former steelworker to transition to college student.

On the first day of school, I arrived at Bobby’s house several hours before he needed to leave for his class. My intention was just to be with him, talk and get him used to having me around. I still brought my photo, video and audio gear. I was prepared, and that would end up being a good thing.

Bobby was welcoming, but I sensed that he was a bit overwhelmed. Compared to his calm demeanor at the bar, he looked antsy and distracted. He saw my camera bag, and he said, “So I have a few things to do. You can just do what you do with that stuff.” And so I did.

When people have a new person in their home, I would think that they entertain and keep the visitor company. Normally, I think that Bobby would have, but with so much on his mind, he just went about his business. And since we had already connected in person, he trusted me.

Bobby started going through paperwork, making a few phone calls and collecting his books. With his mind on school and this new chapter of his life, I took out my camera and began making photographs. He didn’t flinch. I became the fly on the wall and was able to begin documenting his story.

Bobby moved from living room to dining room to kitchen. He even went to Walmart to purchase some school supplies. I followed him around to each locale and made images along the way.

Eventually, it was time to head to class. As Bobby was packing up, I noticed that he started breathing heavier, was using curse words and becoming flustered. He suddenly was misplacing things. He frantically went from room to room and he was in a rush mode. All along, I was photographing and witnessing this frustration. I thought that the still image might not completely convey the situation, but I hesitated to do video and audio. It was our first day together. Plus, he was obviously overwhelmed with the thought of school. I thought I might add stress by introducing microphones, tripods and cameras all at once. So on the first day, I only made photographs.

TID:How did you process what went on the first day you documented Bobby?

Eric: After I left Bobby on his first day of school, I called my girlfriend to share what had happened. I recounted the day’s activities. In addition, I commented on his frenetic behavior and nervousness. The ensuing conversation went something like this:

GF – “What was it like being there on the first day?”

EK – “I was amazed that he just let me into his life and allowed me to start telling his story. He welcomed me into his home and just went about his business. We did this. We did that. When he was going to school, he certainly seemed bothered and nervous.”

GF – “How did his behavior make you feel?”

EK – “School is so new to him, and I think he might have a tough time getting integrated with the classes and environment. But I certainly hope he succeeds.”

GF – “That is good, Eric. But what were you feeling while watching him?”

EK – “If I were in his shoes, I think that I would be the same way on my first day of school.”

GF – “Eric, I got it. BUT WHAT DID YOU FEEL?”

EK – “I think… I think…”

GF – “Stop thinking and start feeling. HOW? DID? YOU? FEEL?”

EK – “I felt frustrated and nervous for him. I felt restless and uncomfortable combined with a little sense of hopelessness. I felt like helping him and consoling him and talking him through it. But I couldn’t. I felt somewhat sorry for him. He shouldn’t have to go through this. The life he knew for such a long time is now gone, and he is going through something difficult and new.”

GF – “Eric, you are seeing and feeling. Did you capture that?”

EK – “No, I don’t think I really did.”

GF – “Now, the next time you are with him, capture that. Show ME. Make ME feel what you are feeling. Make ME feel what Bobby is feeling.”

TID: How did that conversation lead to the video?

Eric: About one week after his first school day, Bobby was doing an Algebra assignment at home in preparation for his class. As I drove to visit him, I wondered if I would witness any of the same nerves and frustrations that I had seen on the first day of school. With that thought, and my girlfriend’s advice fresh in my mind, I decided that I would capture only video and audio that day.

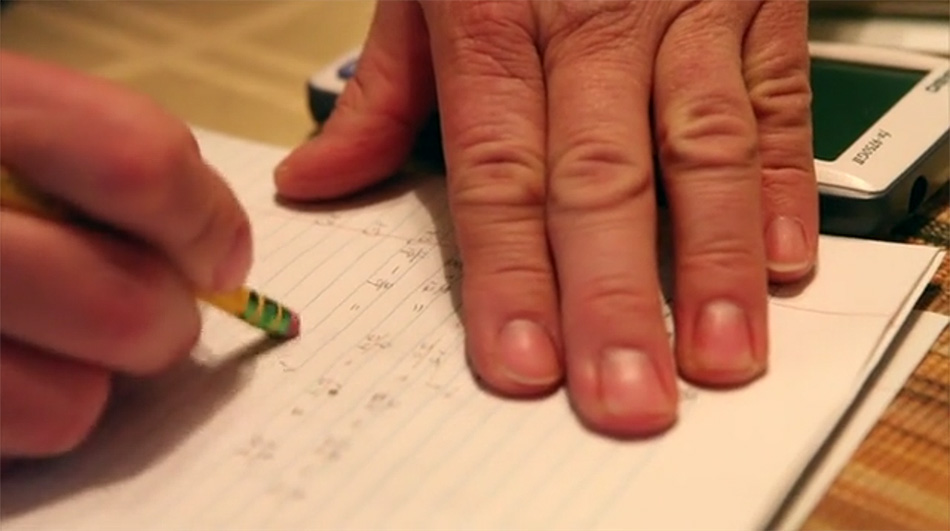

When I arrived at Bobby’s house, he was hunkered down in the dining room. Books and papers were strewn about the table. His head drooped over his calculator. As I came into the room, he talked about how difficult the problems were. I told him that I was going to film him doing homework. He was okay with it, so I prepared my audio and video setup and sat down at the table.

Instantly, I could not only see, but I could feel, that Bobby was frustrated. He had been at the Algebra for about 30 minutes before I had arrived, and he was struggling with the assignment.

I sat across from Bobby, and I tried to be hyper-focused. As he continued with the problems, I concentrated on visual and audible nuances. His body language. His sighs and breathing. His curse words. Tapping. The sound of an eraser and the crunch of pencil to paper. The ticking of a clock. Flickering shadows. Light. Color. The entire time, I kept thinking to myself, “What is Bobby feeling? How does this situation make me feel? How can I convey it to someone not present?”

For the next hour, I tried to capture everything that I witnessed and felt during his Algebra homework. When it was time for him to pack up and head off to school, I remembered the frenetic first day. Once again, he displayed those emotions of irritation, and I continued to film.

After returning home that day, I once again talked with my girlfriend. I mentioned how he was struggling with his homework and frazzled with going to class. I really wanted to help him, but I was not the tutor. I could not interfere. I was the storyteller.

TID: How do you juggle gathering multimedia content?

Eric: When going into a new scene, it is oftentimes difficult to know whether to shoot photo or video. Being one person, I feel like I have to choose. If I try to do too much in one situation, something is going to suffer. Returning to a situation grants a benefit – it allows me to learn time and again, and it offers me an opportunity to change my vantage point, perspective or medium. If I don’t have the luxury of returning, then I assess the situation in the best way possible, make a decision on what will best convey the story, capture what I can, and just do my best.

TID: Was there anything that you learned or put to use in later assignments that came about from this experience?

Eric: Whenever I begin documenting a new story or am given an assignment, I first recollect the conversation that I had with my girlfriend. Then, I talk with the new people, learn what they are going through and try to understand what they are feeling. They might not open up as quickly as Bobby did, and that is okay. Be patient. When I am with them, I look for the same things that I looked for with Bobby – gesture, language, expressions, etc. As I tell their stories, I constantly try to find ways of capturing and conveying their emotions. But every case is different. In Bobby’s situation, he was frustrated and overwhelmed. The channel through which those feelings arose was math. But for the overall story, it really wasn’t about math. I wasn’t trying to show his shortcomings with the subject. It was about showing emotions that any viewer can relate to. We have all been frustrated and overwhelmed. And our channels for that can range from relationships, family, job, etc. So it wasn’t necessarily about the channel, it was about the feelings. So with new stories, I look for the emotions present: fear, anxiety, enthusiasm, loneliness, etc. Then I look for visual / audible expressions of those feelings, capture them and weave them together into a narrative.

I think the biggest lesson I learned by documenting Bobby’s story was that effective journalism not only tells a strong story, but also offers insight into our similarities as people. Journalism makes stories relatable. It helps us understand, and question, and most importantly, it evokes emotion. In essence, it makes us feel, well, human.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In addition to covering his preferred subjects, Eric has a passion for teaching photography, storytelling and the creative process. He is a photography workshop leader with National Geographic Student Expeditions and Lindblad Expeditions, where he travels the world guiding adults and high school students.

Eric's work is represented by National Geographic Creative.

www.erickruszewski.com

Twitter

Instagram