Spotlight on Daniel Milnor

Nov 2, 2012

TID:

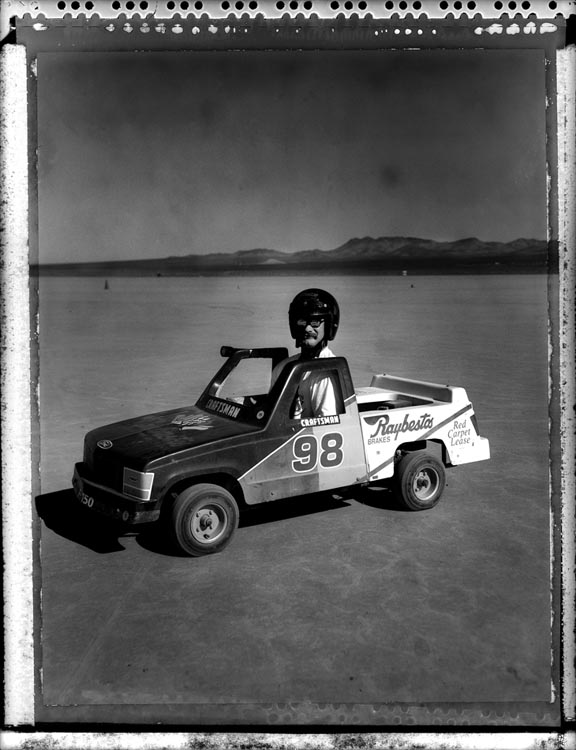

This is great. What an unusual image in an unusual landscape. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

DANIEL:

The backstory is about a long-term project, dust, high-octane gasoline and little luck at my side. This image was made at El Mirage Dry Lake in the California desert, a strange place where you never quite know what you might run into or what you might see. I’ve seen adult movies being shot and people camping in black tents in the middle of the summer. In short, it’s awesome. The catch on this particular day was that I was on my motorcycle with my 4x5 strapped to the back. I saw a dust cloud, came across big guy in little car, asked if I could shoot and the rest is history.

TID:

Since this image is part of a larger shoot, can you talk a little more about the project?

DANIEL:

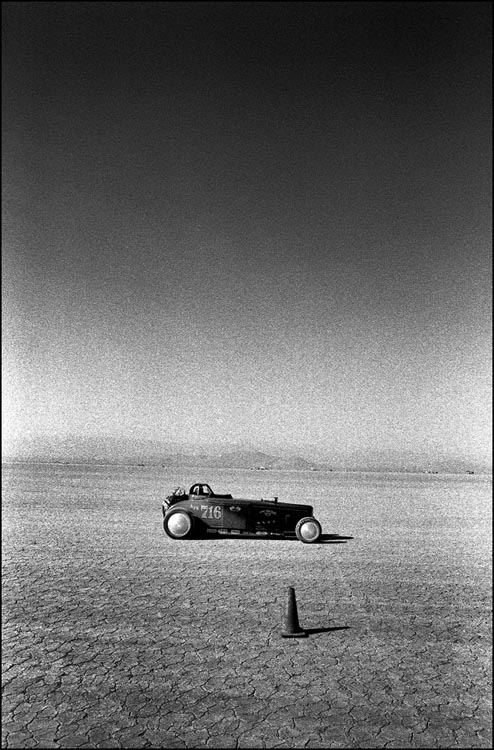

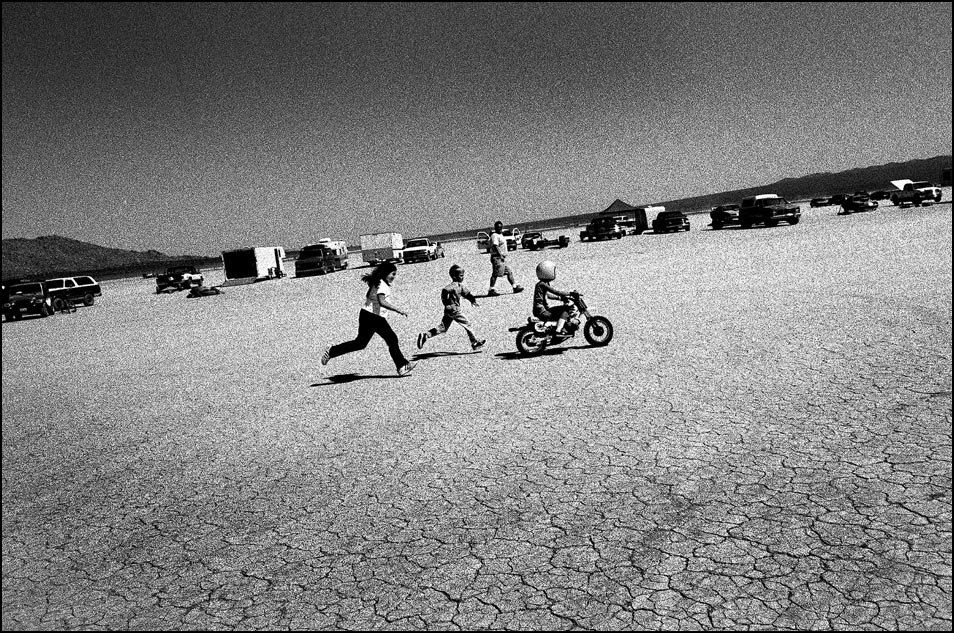

This image was part of a larger story on something called California Off-Highway Vehicular Recreation Parks. Yes, it's a mouthful. These parks were created so that those people with outdoor toys, things like quads, bikes, buggies, etc. would have a place to play without blazing across the entire expanse of the desert. Problem is, after the parks were created, several environmental groups came in and decided the parks should be done away with. This, in turn, led to a long-running battle between organizations like the Sand Association and the Sierra Club. This story was just one chapter of a larger project called “Man vs. Nature,” something I worked on for about ten years. In some ways, I’m still working on it.

TID:

How did you prepare for this project, or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

DANIEL:

The truth is I was entirely UNPREPARED for this project. I was working for Kodak at the time and was working with a camera dealer somewhere in the Inland Empire. I didn’t know this guy well but he inquired about what I did outside of Kodak. I told him about my photography and this project and he said, “You know about Glamis right?” “What’s Glamis?” I asked. He smiled and several weeks later blew my mind. Turns out he was a high-octane kind of guy with custom made buggies and Glamis was the most amazing set of sand dunes I’ve ever seen in my life.

Several weeks later, over Thanksgiving weekend, I drove to Glamis to find 250,000 people and a type of nitro-blown insanity I could have never imagined. We strapped into one of his buggies, complete with helmets, harnesses, etc. I knew I was in trouble. I had a Leica around my neck and he looked at me and said, “You sure about that?” I told him I needed to be able to shoot as we were driving. Roughly one minute later we were at about 80 mph and my Leica was entirely full of sand. Ruined. Done. Gone. The dunes at Glamis proved a remarkable experience, and was the first place I began to get a better understanding of the parks, the people involved and the battle going on between those in favor and those against.

Luckily, I had a second Leica. I needed his help getting into the dunes, so he carted me around, scaring the living Hell out of me in the process, but I was able to make my first few images on the project and knew I was on to something that fit my style of image almost perfectly. Most of the project was done with 35mm black and white film and a Leica, but I wanted something for the first and last image, something very different, that would hook viewers in a certain way and I knew the 4x5 and Polaroid Type 55 would be perfect. Also, the Leica is fast and the 4x5 is the polar opposite, requiring an almost formal approach. The 4x5 is about commitment. You don’t even take it out unless you have made a multitude of decisions. I love giving myself these challenges.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

DANIEL:

There were several challenges. First, I was on my motorcycle. To get to where I made this image required about 120 miles of highway, then dirt road and then ultimately onto the lake surface. I was riding a 600 v-twin Honda dualsport bike called a Transalp with saddle bags on the back. Across the bags I had my 4x5 Crown Graphic, tripod and bucket filled with clearing agent for the negatives. The lake surface is patchy in places, loose and doesn’t mix well with bike tires. And, I’m on a dry lake so my first instinct is to see how fast the bike will go without ruining my equipment, crashing or worse. The second issue is the dust. It’s like talcum and gets into EVERYTHING, including negatives and clearing solution. I knew the negs would suffer from the elements, but that was what made it so fun, not knowing, not being certain and coming to grips with the fact that perfect is boring. I want unique. Working with this camera, in that light and those conditions is very slow, tedious even. I shot three frames total. The first was terrible but the second and third ended up being the first and last image in the series.

The only thing that pains me about this image is the fact I lost the man’s contact information, which is something I RARELY do. I’ve never been able to talk about it with him. I would love to hear his thoughts. He was a very nice individual with a great sense of humor, someone who deserved to has his image, and this moment, made and preserved.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems? (Problems are not unique, but what is unique is a photographer's ability to problem solve.)

DANIEL:

I overcame the issues by continuing to move forward realizing there was nothing I could do about any of the issues. I chose to ride my bike out there, into the unknown. I choose to shoot 4x5. I choose to use Type 55 and I knew the consequences, but as they say, “the cure for boredom is ADVENTURE.” Problems make life interesting. I’ll equate it to my current life. I do A LOT of public presentations. Sometimes I like to do presentations without knowing specifically what I’m going to do or say. I might have a presentation but I might not ever look at it until I’ve been introduced and the crowd is looking at me in silence. I think some people might be horrified by being put in that situation, but I actually love that feeling of heightened focus. Photography and situations like this are precisely the same for me.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture.

DANIEL:

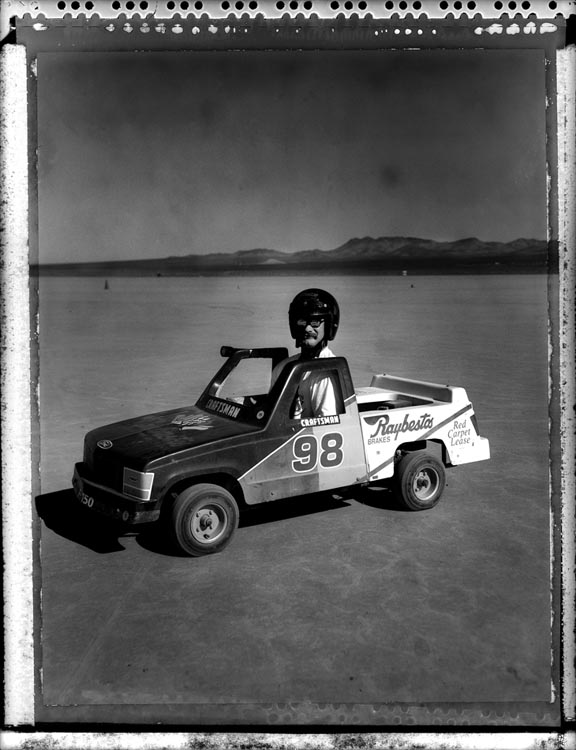

In this case it was simply about seeing a dust cloud and aiming the bike in that direction. When I saw this guy I knew it was the photograph I was looking for, so I asked if it was okay to make his portrait. He agreed. I began the great unpack and he did doughnuts in the tiny car, kicking up a mini dust storm. The light wasn’t great but in the desert you get about twenty minutes total of good light. At that point it was about engaging the person, telling him about the project and what I’m doing behind the camera, and then allowing him to play, to act, to be someone entirely new for the split second I need him to be. This is such a great moment. Something happens during that moment, something that will never happen again, something that will never be the same. Our lives will forever be slightly different because of this moment. It’s magic. I made two frames of him, the first is really to break the ice, and the second is the image you see here.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

DANIEL:

I’m surprised anytime someone agrees to be photographed. We live in a different world today, a world in which sometimes you are guilty until proven innocent. The camera I was using was really old and falling apart. In fact, a small part fell out during this portrait and landed on the ground. I acted like it was normal and he didn’t seem to mind. I have no idea what the part actually did. I just left it there. People loved this camera. After I made the exposure I pulled the Polaroid, waited about two minutes, pulled the negative from the backing and he was able to get his first look at his image. I took the small vial of sealer and coated the print before putting the negative in the clearing solution. Again, this was a way of engaging with him because people really don’t see this type of work anymore. It showed him I’m not a happy snapper working quickly. It showed him I’m concerned about things like process, artifacts and preservation, things not normally associated with modern photography.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

DANIEL:

I’ve learned that I am hopelessly addicted to recording things. It’s a curse, really. I’ve had it since childhood and photography is the latest incarnation of the addiction. I’ve learned I don’t really need to show this work to anyone. I’ve learned I’m not interested in being known as a photographer. I’ve learned the hunt is as much a part of the experience for me as the capture. I’ve learned that this work takes more time than I actually have. I’ve learned just how lucky I am to even be able to do this work. And I’ve learned that creatively speaking... I haven’t even started yet.

TID:

What have you learned about others?

DANIEL:

People want to help, to be involved; consequently, they are the most important ingredient. I’ve learned that the people in my photos don’t see photography in the same way I do, so I need to attend to their needs, fears, suspicions or ideals. I’ve also learned that everyone has a story, and that is really all I am: a storyteller. But I also see this as a very important role in society. People are constantly surprising me. I recently photographed someone I thought was going to hit me, and it turned out he was puzzled by me and was entirely curious, not angry. We are an unbelievably complex species, one which I’m still trying to figure out.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

DANIEL:

Ignore anyone who tells you that you need to work in a certain way. Be truthful, take your time and shoot ONLY what you feel you need to shoot. The vast majority of people in the world don’t have a camera or computer and don’t care about your work, so stay humble and keep things in perspective. Remember, this is supposed to be fun, so enjoy the journey, the process and the spoils. And if you ever see a giant guy in a little car, tell him I’m still looking for him.

:::BIO:::

Daniel Milnor is currently “Photographer at Large” for Blurb, Inc. the world’s premiere print-on-demand publisher. He splits his time between the smog-choked arteries of Southern California and the spiritual landscape of New Mexico. Milnor is a former newspaper, magazine and commercial photographer who now works primarily on long-term projects. His work has taken him from the rural corners of the United States to Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America.

He has taught at Art Center College of Design, Academy of Art University, The Santa Fe Photographic Workshops, The Julia Dean Workshops and the Photo Experience Workshops. An early adopter of select technologies such as print-on-demand books and magazines, Milnor has created and published over one hundred unique titles, including the recently released “Manifesto Magazine,” which showcases the world’s best documentary photography. Milnor’s writing and photography has been featured in Camera Arts Magazine, Black and White Magazine, Life Magazine, Zone Zero, Flash Flood, Finite Photo, Resolve, Hasselblad Gallery as well as many others.

He recently began a long-term mentoring program for photographers wishing to learn more about producing in-depth documentary projects.

Additionally, Milnor is the author the blog Smogranch which allows him to speak his mind, post his mother’s poetry and bring together like-minded people around the globe. His work is in the collections of both The Los Angeles County Museum of Art and The George Eastman House.

You can veiw more of his work here: