Spotlight On Craig Walker

Feb 12, 2012

TID:

Hi Craig, thanks for your participation. Would you start by telling us a little about this project?

CRAIG:

It all started in early 2007 when my bosses met at a bar for an after-hours meeting, where a speech by President George W. Bush regarding the troop surge in Iraq was airing. As you may recall, the war wasn’t going extremely well; it wasn’t very popular and recruiting was down. As they were watching Bush’s speech, Damon Cain, our managing editor asked, “Who would join the Army now?” Thus, our story idea was born.

The Denver Post’s director of photography, John Sunderland, suggested we follow a recruit from high school to a war zone. Our assistant managing editor for photography, Tim Rasmussen, saw the potential. He approached me and I loved it. He challenged me to do the best work I’d ever done. I started with public affairs at the Denver recruiting office. I told them we were looking for someone who was eager to fight honorably for our country, but someone who was also interested in signing up for the infantry, knowing they would ultimately end up in a war zone.

The woman at the recruiting office told me of two seniors at Bear Creek High School who might be a good fit. I started working with a young man who, after spending two weeks with him and his family, decided not to join the Army. I respected his decision, but with graduation less than a week away, I was a bit concerned as to what would happen to the story. I remembered though, that stories must take their own turn. Sure enough, when I met the second high school senior and his family, I felt good about how things were developing. I liked Ian Fisher immediately. He was tough, young and eager – a leader in his group of friends, all of whom he’d fight for. He similarly had that quality for his country.

So the two-year journey of American Soldier; Ian Fisher began. I followed Ian from high school graduation through basic training to his first deployment and home.

TID:

You said Tim really challenged you and helped you grow. That may surprise some readers since you were already a seasoned photographer. Will you talk more about how he did that?

CRAIG:

Tim’s awesome. I know we agree there’s always room to grow and learn, especially in our field. And though I’ve been shooting photos the majority of my life, it had been a long time since an editor posed such a challenge.

“Do the best work you’ve ever done,” Tim said. But what did that mean? I had ALWAYS done the best work I could do because I love photojournalism. So I obsessed over every aspect of the story – from conducting intimate video interviews and doing extensive reporting to being sure I was with Ian at all the right times.

Tim was a great navigator during the project. He made sure to keep the story alive through the ever-changing and tumultuous waters of the industry. His intensity matched mine in many ways, but when his focus was needed elsewhere, I stayed determined.

TID:

I've heard that reporters came and went from the story and that ultimately, you shared a byline in the written piece as well. Talk about your note-taking and writing process.

CRAIG:

In the two-year course of Ian’s story, The Post used three different reporters. I knew, because of the changes in writers, that it was important for me to be hyper-aware of important details that might add to the written story.

Naturally, I spent a lot more time with Ian than the reporters did because that’s how you tell stories with pictures. I kept good notes all the time, but I kept meticulous notes when the reporter wasn’t around. Rather than just jotting down a great quote or moment, I’d write using a “day in the life” format. I wanted to be able to offer verbal scenes and quotes to the written story as well as imagery.

And my notes came in handy; there was about an eight-month period when the reporter was not actively working on the story because of the political race he was following. So between my notes and the video interviews I had done with Ian, his family, friends and platoon, I was able to give the lead writer a great deal of insight.

TID:

How did you balance such a long-term project as this one with your other responsibilities at the paper?

CRAIG:

As you may recall, The Rocky Mountain News was our competitor at the time. So when I ran into photographers on daily assignments and they would say, "Hey Craig, I haven't seen too much of you lately…"

I would reply, "Yeah, I've been working on the desk a lot." (Ha ha ha… Yeah, for two years.)

Though when I wasn’t working on the project, I tried to shoot daily assignments as much as possible. I had a huge amount of support at the office. Everyone knew what I was working on and they were flexible with my wavering schedule.

There wasn’t a set schedule as to when I’d work on the story or when I’d work on daily assignments. There’d be long stretches – weeks at a time – where I wasn’t in the office at all. I’d spend the other times editing when I could and shooting daily assignments as needed.

The most difficult time was when Ian was assigned at Fort Carson, just an hour from his home and high school friends. I knew there was always a possibility that I’d need to drop whatever I was doing and connect with him.

TID:

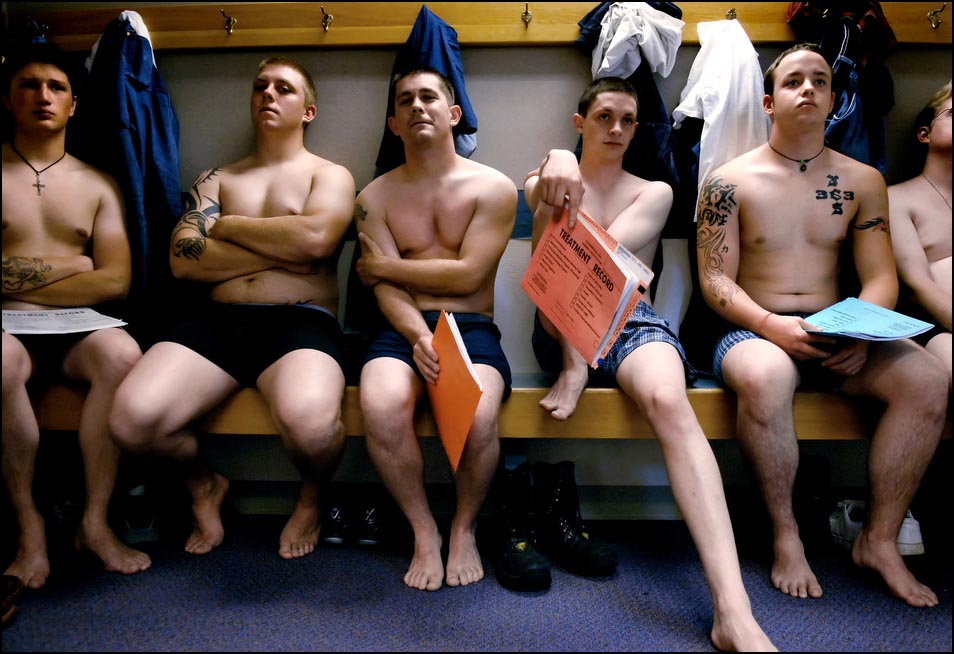

This image communicates so much. Tell us a little about making it. What was going on in your mind at this moment?

CRAIG:

At this moment, Ian was looking for a way out of his commitment to the Army. He had injured his elbow and saw that moment as his opportunity. He was suffering from sleep deprivation, culture shock and stress - as was I. Two days into processing, when I shot this picture, I was wondering if my story was over. While I also thought it was a powerful image, I was too worried about the story taking a nosedive to realize how much foreshadowing it contained.

TID:

It can be really challenging working within the military. Talk about those challenges and your approach to them.

CRAIG:

From the beginning, our biggest concern was that we would start the project and have trouble following our subject through the rules and guidelines that make up the Army, so we knew we needed the Army’s approval from a high level.

Fortunately, I was introduced to Major Anne Edgecomb, a public affairs officer at the Pentagon. Maj. Edgecomb appreciated the story immediately. Ultimately, it was my responsibility to gain the trust of the soldiers Ian worked with, but Maj. Edgecomb opened doors and made those vital introductions.

When I was with Ian, I wanted total access, unaccompanied by a public affairs officer. I wanted to live his life. So I asked to be an embedded journalist throughout the project. But it wasn’t until I entered the Denver Processing Station early one morning to a roomful of underwear-clad recruits awaiting their physical that I realized all my legwork had paid off.

TID:

You mentioned before that you went you through a bit of culture shock and sleep deprivation? Can you more talk about that? I imagine at times it was if you were going through boot camp as well.

CRAIG:

To make the best images, I needed to live my life as Ian was living his, which involved culture shock and sleep deprivation. The first week of processing and basic training were the worst. With the drill sergeants yelling through the constant marching, exercise and 30 seconds to eat, I understood why some recruits questioned their decision to join the army.

TID:

Were there any moments of conflict while shooting, and if so, how did you handle it?

CRAIG:

In Iraq, Ian was assigned to the Quick Reaction Force, which responded to emergencies on and off the base 24/7. So when there was an attack, instead of taking shelter in the bunkers, we jumped in the vehicles and sped toward it.This could be stressful but my moments of conflict had little to do with photographing soldiers on the front lines or working in a hostile environment. Instead, my difficulties were with people who didn’t trust “the media” or understand what I was doing.

There were a number of people who told me they didn’t want to be photographed. If those people were important to the story, I would take the time to explain to them the story’s mission and why their role in it was necessary.Those moments, though, were few and far between, and I always found that an honest conversation was the best remedy for potential obstacles. Ultimately, the people who were most important to the story understood it and were okay with being part of it.

TID:

Talk about your relationship with Ian. It can be hard just keeping in touch with subjects, particularly teens and young adults. Was it hard shooting when he was with his friends? If so, how did you handle it?

CRAIG:

It helped that Ian and his family understood what I needed - the kind of access and time it would take to tell their story effectively. Once Ian and his best friend “Buddha” introduced me to their “posse” and approved my status in their group, I was welcomed with open arms. I think it also helped that I had a son at home around his age.

Working with Ian came hand-in-hand with learning to text message. When he wouldn’t answer a phone call, he would most likely respond to a text – that I learned quickly.

TID:

Was there any sort of initiation you remember? Any one moment that made you realize you were "in" with them?

CRAIG:

I mostly built relationships with Ian’s friends through lots of short conversations. But I do remember a situation where I was photographing beer pong at a party. I was shooting on the floor next to the table, when a beer cup fell over and spilled on me. Everyone there laughed, and when I joined in their laughter, they appreciated my ability to laugh at myself.

TID:

How did the project run in the newspaper? Will you describe that decision-making progress?

CRAIG:

It ran as a three-day series, starting on the front page and jumping to five inside pages everyday. We ran 52 pictures in the paper. Originally, I was hoping the project would run as a special section, but I’m glad it ran as a series, because in the end, I think it actually got more space.

Once the story was scheduled to run, I was involved in just about every meeting. In fact, the only time I missed a meeting was because I was editing or captioning for the web. Tim and the other editors kept me so much in the loop, I didn’t worry about missing anything. Come time for publication, Tim and I found the biggest conference room available at The Post and created a visual timeline for the story that was pretty close to the final edit. This helped the layout develop, and was a tool the editors and designers used to create the story in the paper.

This might be a good place to mention Meghan Lyden, our online photo editor. She produced the entire website from scratch. She watched over 130 hours of video (twice!) before she started editing. She's great.

TID:

If you don't mind, will you talk a little about winning the Pulitzer Prize (for feature photography in 2010) and if/how this has changed your work dynamics?

CRAIG:

Though it may sound cliché, winning the Pulitzer Prize was truly an amazing and humbling experience. When the story was published, I really felt that it was the hardest and best work I’d ever done, so for it to be recognized with a Pulitzer was really special.

I don’t think winning the Pulitzer changed my work, but I do think I learned a great deal from the story that won the honor. I believe working so intensely for so long on a story really challenged my skills. All those things I thought I was good at, from being the lead person on a story and scheduling meetings, appointments, flights and embeds, to simply being more patient - those things I improved on, and I think they’ve made me a better journalist today.

TID:

What did you learn from doing this story and getting to know Ian? What did you learn about yourself?

CRAIG:

As a photojournalist, I’ve done stories on all kinds of people, but working with Ian the way I did gave me a different perspective on his generation. It also confirmed that every soldier is an individual, and shouldn’t be stereotyped.

I learned I can be a little obsessive, and I need to work on that. But I also learned that had I not been obsessive, the story might not have reached its potential. There is a fine line between being passionate and obsessive to being unhealthily fixated and not able to do a good job. That line can become blurry from working on something so intensely for so long.

TID:

What advice do you have for other photographers?

CRAIG:

Be patient and listen. The story is about your subject, not about you. When Ian was about to be thrown out of the army, I was extremely upset thinking my story might be over. But it wasn’t about me. Good photojournalism is never an “I” or a “me” thing. In fact, the situations that are most frustrating also tend to be the most interesting for the viewer.

People have told me, “Have no preconceptions. The story will unfold for you.” It’s true.

***

Craig F. Walker is an American photojournalist. In 2010, Walker won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography "for his intimate portrait of a teenager who joins the Army at the height of insurgent violence in Iraq, poignantly searching for meaning and manhood." He is on staff at the Denver Post.

After growing up in York, PA, Walker attended the Rhode Island School of Photography, graduating in 1986. He worked for the Marlborough Enterprise and the Berkshire Eagle prior to taking a position with The Denver Post in 1998.

***

Next week we'll take a look at this wonderful image by Alex Boerner:

If you would like to interview someone, or if you have any suggestions, contact Ross Taylor at: