Spotlight On Chris Tyree

Oct 15, 2011

CHRIS:

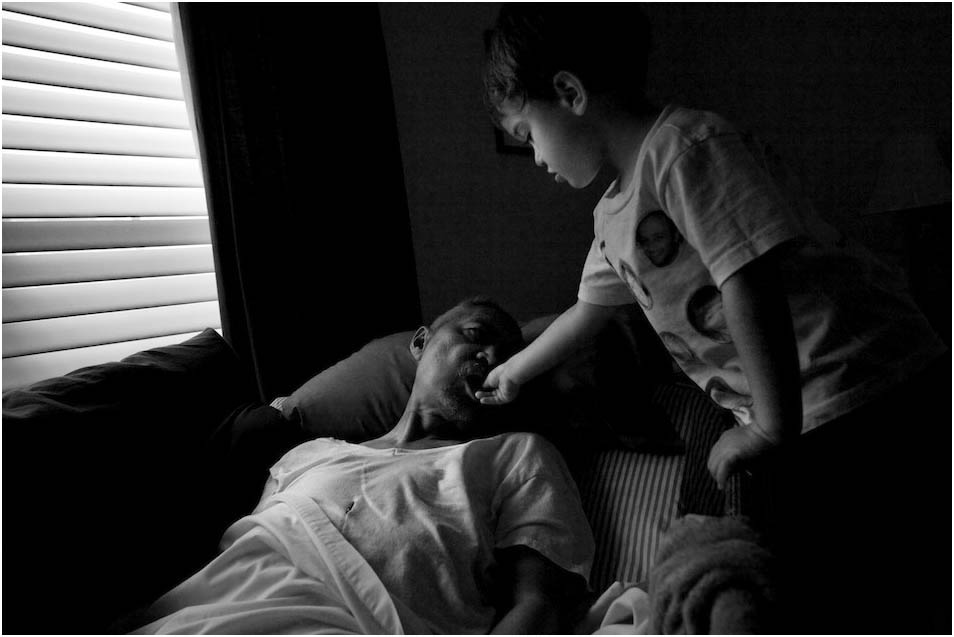

The project was called Summer's End, and I photographed

my father-in-law's final days as he succumbed to cancer. It

was as much a project about how we, the family, deal with

loss, deep love, and hope. These images I'm sharing came on

the last time I saw him alive. It was earlier in the day when I

made them. He passed away that night.

The project actually started when I'd stopped by after work

and had my camera with me. My son Jack had been at

their house with my wife since the morning and had gotten

use to seeing his grandfather in the bed by that point. Jack

had just turned three a couple months before. As I walked

into the dark room I saw Jack feeding his grandfather ice chips.

It was the last solid food he ever had. There was something

about watching my little baby taking care of his grandfather

and I snapped a few frames. That night at home I looked at

what I shot and started crying. I felt that I needed to do something

or say something and it hit me in the face that what I needed

to do was not show the agony or pain, but show the devotion,

love and life that was going on around that dark room.

TID:

You said you needed to do something, or say something. Why did

you feel that way, and what did you do about it?

CHRIS:

Over the years I’ve had assignments that dropped me into the

emotionally tumultuous lives of complete strangers. Some

really serious life and death issues, ya know? I never felt like a

vulture because I’ve always tried to establish a good relationship

right up front, but being in such a personal and intimate situation

with the focus of making a storytelling photo can make one feel

both exposed and vulnerable. I can only imagine what it must

feel like on the other end of the camera. The way I’ve always

handled these situations was to just to be me and be honest with

the subjects. I’m not an aggressive shooter by any means and,

maybe I shouldn’t admit this, but there have been many times when

I felt that making the image wasn’t worth the price the subjects

would have to pay and so I didn’t raise my lens. There is this

crazy balance in my mind, “What does making this image mean?

Will photographing the situation shed light on a larger issue that

needs to be addressed?” Then I hear myself reiterate something

I heard James Nachtwey say once, “If you don’t shoot it, who will?”

It all gets weighed together with the news value of the story and

the emotional place of the subject matter. Generally speaking,

the answer most often came back that the power of the intimate

situation provided a necessary moment to telling the larger story

that could have a profound impact if seen and so I snapped the

shutter.

But, what if it was my family... I really did think about that

sometimes when I was facing one of those situations. How would

I feel if someone was making a picture of me or a loved one

facing a serious situation? There is no easy answer. There never is.

So, when I walked into that room and saw Jack feeding his

grandfather ice chips I conjured up those questions again and

I had a really hard time answering them. But what dawned on

me was this: How could I make pictures of dying children or

victims of awful tragedy if I couldn’t focus a camera on the

people close to me too? And so I snapped the picture. It seemed

like too much of an important moment in the lives of everyone

involved not to be memorialized. Later that night when I started

reflecting on it and all the images I’ve ever made in similar

situations I felt like what I have been focused on for most of

my career was the tragedy right in front of me and not the life

that moves around it. Often it was the news of the day and that

mandated that I shoot from that more limited point of view. But

I started thinking, where there is pain and anguish there you can

also find love and compassion. That was the expression on Jack’s

young face and Pop’s sunken one.

So, I went back the next day to show my father-in-law, Pop,

the image and talk to him about what it meant and the realization

the photo brought to me about life revolving around him. It

wasn’t an easy discussion for me but he understood and knew

that telling it could help others be more at ease if they were in

his situation. He was so gracious.

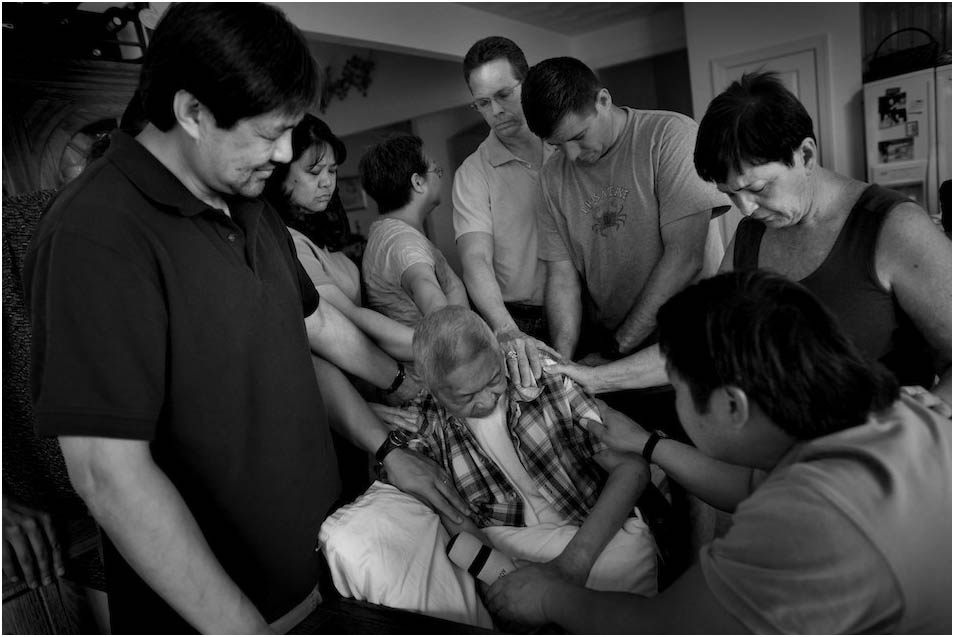

And so, for the next few weeks of his life I focused on a story

of devotion, love, loss and rebirth.

TID:

You said in a previous email that you called the project "Summer's

End." Why did you name it that, and to what extent did you document

him?

CHRIS:

The name of the project is actually quite literal. Pop died as the

summer faded with most of his family keeping vigil at his home.

But it meant more to me too. Pop was always like the sunshine,

warm and happy. He filled a room with his shining smile. He was

summer in a body. I don’t think he liked the cold either, really.

He grew up in the Philippines and was happiest in brutal heat.

The other thing I liked about the title was this: it conjectured that

there would be something coming after summer. That life would

continue, just differently and just as beautiful if we care to look.

I was lucky that I was working at The Virginian-Pilot at the time

and was given time off not to necessarily work on this project, but

to also be there for my family. This was a pretty emotional time

for my wife as you can imagine. She loved him to pieces. So, I was

able to spend most of three weeks documenting this project. Many

times just spent sitting with him holding his hand and talking to

him about the times we spent rock hopping in El Paso, playing

golf and taking care of his “girls."

I think that is a really important lesson that is often overlooked or

an essential tool that separates the good from the great, that ability

to listen and be patient. To be in the moment and not necessarily

shooting it. When we are IN the moment, then everything we are

seeing, hearing, and feeling will come through the photographs

that follow and they will be powerful images that you can’t turn

away from.

TID:

Lets back up some. Did you have an initial thought to document

his final days, or did it stem from this day alone?

CHRIS:

Pop had been dealing with cancer for several months and though

I’d made a few pics here and there for some family events and

things, I guess I was shielding my innermost feelings and also

struggling with what to say visually about it that would add

anything new to the thinking about cancer or death.

I didn’t see the story that early and that was my mistake maybe.

I don’t know. Maybe it was fortunate that I didn’t see it so clearly

then and that it hit me near the end. Because for me, the focus

wasn’t about a person suffering from cancer, though that is certainly

an important subject, or a story about a person dying, as powerful

as that is. No, for me it was really about passion and love that

surrounded his bed in that dark room.

The whole project though stemmed from that image of Jack and

Pop. When I saw the love and the intimacy of the moment, I knew

what the focus would be and that I did have something to say with

my images that could be shared and contemplated for a deeper

understanding of what death means to all those involved. It was

the idea that there is so much love and life going on around him.

Ironically, I had already shot the bookend to this story on Pop a

year or so before when I photographed a story about Jane Does

and unclaimed bodies. How empty and sad that made me feel to

think about people who once were part of this community of life

and then were lost to the abyss with not so much as their name

placed on the ground above their name. Just a number, if even

that.

I thought about that story when I was looking at the picture I

made of Jack and Pop, it was a profound moment.

TID:

Now, lets talk about the image itself. Can you walk us through

your mental state that day before, as well as within, the moment.

CHRIS:

On the day this picture was made I’d actually gone into the

office to work and had an assignment to photograph at a

graveyard. I kind of remember thinking that that was a crappy

assignment given my circumstances but maybe it was just part

of the journey, ya know. I got over to Pop’s kind of late in the

afternoon and it was really quiet in the house. It seemed a bit

abnormal because for the previous three weeks there were people

constantly coming in and out, especially the grandkids.

It was evident that the mood was heavier and Pop’s wife, Sandi,

my wife, Mel, and her sister, Olivia, were in the room with him

when I walked in. Mel was crying by herself nearby and Olivia

and Mom where nestled by his bed. I made a few pics then took

Mel out into the living room for a while to talk. Pop’s breathing

had become shallow and he was sleeping. I was kind of caught

needing to counsel but also feeling the need to document what

was going on. It was kind of confusing. While in the past I had

a single purpose to make the image, here I was feeling that

my duty was to be a support system first and photographer last.

And that is how it should be.

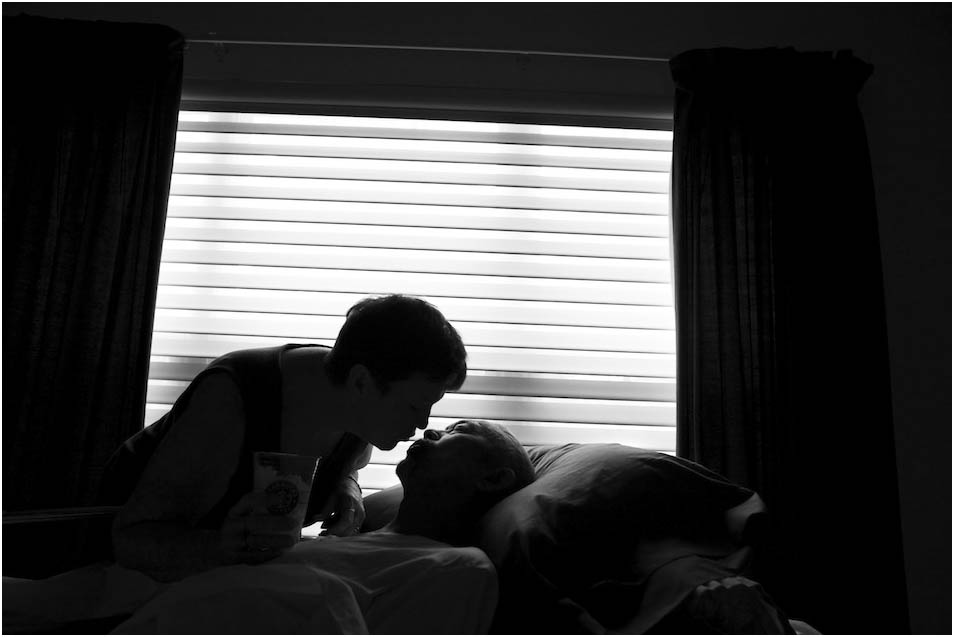

I could just tell that the pendulum had shifted and that the end

was imminent. So I was respectful and really just sat and prayed

out in the living room for a while. When I walked back in, Sandy

had crawled up in bed with her husband. This was the first time

I’d seen her do that and immediately took a frame, then I

remember starting to shoot the scene closer than I usually

would have because there was a tear in her eye and I was afraid the

moment would change. I needed to start close. After I made

that picture, I started to pull back. In the span of about 10 minutes

I made 30 frames. Then I put the camera down and just sat with

my family. That night I went home to take care of things at our

house while my wife stayed the night with Pop. About 1 am I got

a call that Pop had passed away. So that moment of them in bed

together, the unconditional love, the long goodbye, the simple

touch, and the fact that in the framing of this picture they form a

heart has stuck in my head like a brand on a cow. It is one of the

most important pictures I’ve ever made.

TID:

Were there any moments of tension during the making of this

image, or the story? If so, how did you handle it?

CHRIS:

Actually one thing I remember about this day was how quiet

and calm things were in the house. By the point this

picture was made, everyone was comfortable with me being

around with the camera. One thing I never do is constantly

stay in someone's face with a camera. I wait, listen and watch

and only shoot when there is a good or intimate moment. So

when I walked into the room, I knew things were different.

Generally there had been levity around the room every day,

kind of taking the edge off the hardness of the situation, but

not this day. It was serious and still. I think we all knew the

end was imminent and so the family was spending time saying

their goodbyes. If anything this moment was peaceful.

There was never any real tension with the family about telling

this story but there was tension in my own head and heart. I

was still struggling internally about whether this was too

personal or if I was doing the story justice. What was I really

trying to say with the story? All these things were bottled up

and I was working through them as the story progressed.

What I did was to look myself in the mirror and ask myself what

my motivation was. I asked, “What did I hope would happen by

telling this story?” I also had to be confident that I could be both

a supportive husband and a photographer. But supportive

husband first.

TID:

What did you learn about your family during the making of these

images that you didn't know before?

CHRIS:

I always knew how much everyone adored Pop. I knew they would

do anything for him. What I didn’t know was how much they

trusted me to give this project the level of excellence it deserved.

Everyone supported what I was doing and spent time talking to

me about it. Even though I occasionally felt like I was intruding

into really private situations, I was always welcomed.

Some might think it would be much easier to shoot a situation

like this in your own family because of the access, but I actually

found it harder because of how close I was to it. Harder because

my first inclination wasn’t always to take the picture but to offer

support or help out around the house. My focus wasn’t totally about

the photography and I kept having to refresh my mind about the

narrative I was trying to tell with the images.

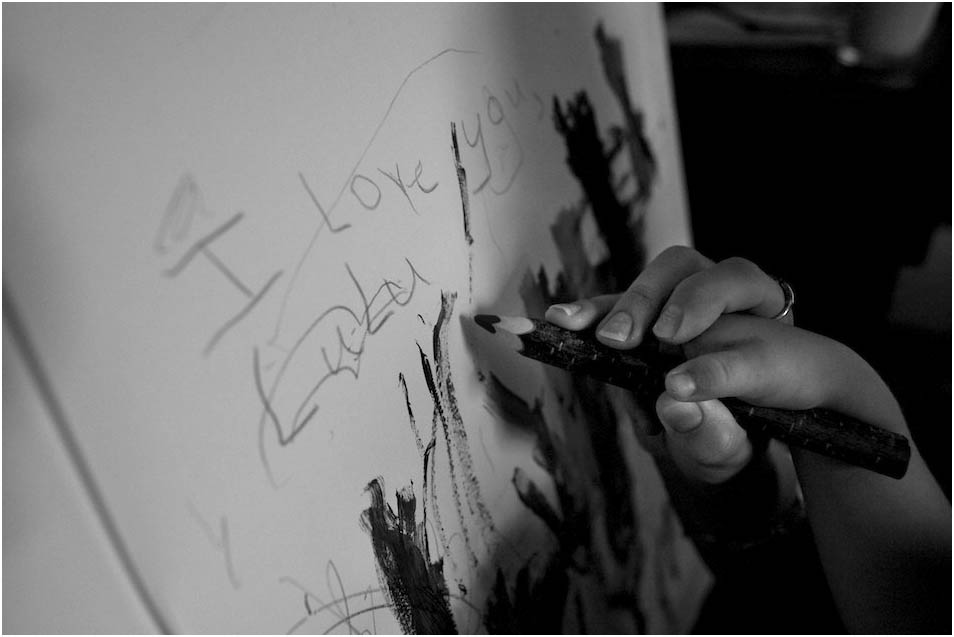

About the only thing that surprised me was how Jack related to

this dramatic scene. At three, he was still a baby but somehow

he realized what was going on but it didn’t frighten him though

he was sad. He was so loving to his grandfather and would

spend hours spinning around in a chair beside his bed while

talking to him.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself?

CHRIS:

I always preach about taking risks and, for the most part, that is

what I’ve done my entire career. Not every risk panned out but

more often than not, the result was often worth the risk. Yet for

some reason, I just couldn’t step off the ledge this time to start the

project. As I reflect on it, I think I learned that I can and should

be more open with my feelings as they permeate through my

camera when the issues are so personal. I also learned that it is

very important to take time with really deep subject matter and

reflect on what you are seeing while trying to make sense of it.

If we are always “on” and not taking the time to let the emotions

burn through our eyes and into our hearts, then we are missing

a greater part of the journey.

The feedback after the story published was so overwhelmingly

positive that I learned that I should trust my instincts more often,

not be afraid to share my personal feelings. I learned that I can slow

down the shooting and be a human being first and a photojournalist

second and still make emotional, powerful and important pictures.

TID:

What would you do differently?

CHRIS:

I believe I bottled stuff up and didn’t trust myself to do this

project in the first place. I also felt like I wouldn’t do it well

enough. And felt like I would be doing my family an injustice.

If I had to do it all over again, I would have had the

conversation with Pop much earlier on.

But in some ways, while I made mistakes, it was all a learning

experience. Photography, like life, is nothing but a learning

experience. I’ve been shooting professionally for almost 20

years now and I’m constantly learning something new about

myself or about photography. The two are married. So I really

wouldn’t do anything differently, even if I knew the outcome

would be the same or better. That’s part of the journey. It is

also what makes me stronger in the future.

TID:

In general, how you do approach intimate situations like

this?

CHRIS:

Quietly. I remember when I was at Ohio University and our first

assignment in picture story class was to go out and tell a story

using one roll of film in one day. All but one of us did a process

story or place story. Really easy projects with no emotional value

whatsoever. But one of my friends came back with an amazing

group of emotional and intimate pictures of a child living with

HIV/Aids. Everyone was blown away. We asked him how he got

such moving images and he basically said that since he was

from Korea and didn’t speak English that great (at the time)

they never talked to him and he just melted into the fabric of

their lives. I’ve carried that lesson with me since then.

I believe in being upfront with what my goals are with the project

and how the images will be used. After that, I just listen, watch,

feel and wait for the defining moments. I don’t click the shutter

unless there is a good moment or a good reason to do so. I give

people space and then work my way closer. I use my body

language to communicate and watch theirs to see when I’ve

intruded too much and then I back off.

The easiest part is making the picture. It is everything that leads

you up to the decisive moment that makes you the kind of

photographer you are and frankly, the kind of person you are

too. I think the best photographers are those who are psychologists,

anthropologists, sociologists, physicists and a bunch of other “ists”

before they are photojournalists. You have to gage the situation,

the moods and expectations of your subjects, the importance of the

moment, the quality of light and then you have to reach deep into

that spirit within you to find your voice both narratively and

artistically. Then you can click.

TID:

What suggestions do you have for photographers, especially

photographers who have never been in these situations?

CHRIS:

There are three things I think photographers should consider

when getting into a situation like this.

First, have a full and deep understanding of what and why. Look

yourself in the mirror and ask yourself if you are doing this

coverage for noble reasons. If you are doing it to pad a portfolio

or win awards, you suck. If you know that you are doing it to

raise awareness and/or interest and have thought about how

the images will be used in the end then you can go to number 2.

Secondly, put the subject of your story ahead of yourself. It isn’t

about you, though the way you see it and the narrative you bring

to it will have your voice. So remember to let the story speak

through you. Give the subject everything you have in terms of

your sensibility and heart.

Finally, don’t be afraid to not click the shutter. That is probably

the hardest thing to say and I’ll probably hear from a lot of people

that you shouldn’t be afraid to take the picture, but I disagree. If

you know your subject well and the story well, then you will know

exactly what you need to shoot and what to watch for. Sometimes

simply watching and being there for the subject is more important

to both them and you as you journey in life. It will be those

moments that you treasure because it showed your vulnerability

and emotional involvement. It is what makes you human.

Chris is the owner of Re:Act Media, director of Truth With A Camera Workshops and an award-winning documentary photographer, filmmaker and writer with more than 20 years of experience covering assignments on nearly every continent for a variety of publications and agencies. Integrity, perseverance, wit and curiosity have been the building blocks for his success.

He graduated with honors from James Madison University with a bachelor’s degree in communication and a minor in anthropology. He earned a master’s degree in visual communication from Ohio University. His photography and editing have been recognized nationally and internationally, earning him numerous awards from esteemed competitions, including Pictures of the Year international, National Press Photographers Association, The Society for News Design, and The Associated Press. Christopher’s photographs have been displayed in exhibitions across the country and are held in several private collections. His work has also been published in many of the nation’s major newspapers and magazines, including Time, Newsweek, and Mother Jones.

You can see his work here:

+++++

Next week we'll feature this surprising and intimate image by Leah Nash:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

[email protected]

[email protected]

For FAQ about the blog see here: