Spotlight On Brandon Tauszik

Oct 31, 2011

TID:

Brandon, thanks for offering to be a part of TID.

Please tell us about the image and the larger project

of which it's a part.

BRANDON:

"On May 21st, 2011 a wave of great earthquakes will occur,

like none our planet has ever witnessed. These will begin the

process of the rapture; as the chosen elect are taken up from

the world to meet the Lord in the air and be forever with God.

All who are without salvation will be left behind. Five months

later on October 21st, God will destroy the earth and all of

the remaining people…"

With this message Harold Camping reached millions of people

worldwide. Leader of the Oakland-based organization Family

Radio, Camping's prediction was backed by a global TV & radio

network, thousands of evangelizers, and countless billboards.

The featured image is part of my project Pray for Mercy, which

follows the organization prior to and directly after the failed

May 21st Judgement Day prediction.

Family Radio paid for a mass of billboard spots in most major

U.S. cities, as well as many other locations globally. Like most

people, I did a double take when I first saw one of the billboards

in early March. With a setting sun behind a silhouetted figure

praying, I was deeply fascinated by the endearing presentation

of the message, which boldly proclaimed the eminent destruction

of humanity.

After reading up on what the media was saying about Harold

Camping’s message, I had to do another double take. It was easy

for people to dismiss him as “crazy”, talking about vanishing

Christians and eternal fiery damnation, but 41% of Americans

believe what Camping believes will definitely happen at some

point in time. So where was the lunacy? In the fact that he set a

date? I feel like a large number of Americans began to privately

ask themselves some tough questions, while ridiculing Camping

and his followers.

All of this both confused and enthralled me. I wanted to take a

closer look at the people perpetuating this message and my

camera was the excuse to do so.

TID:

Where does this image fit in with the larger project?

BRANDON:

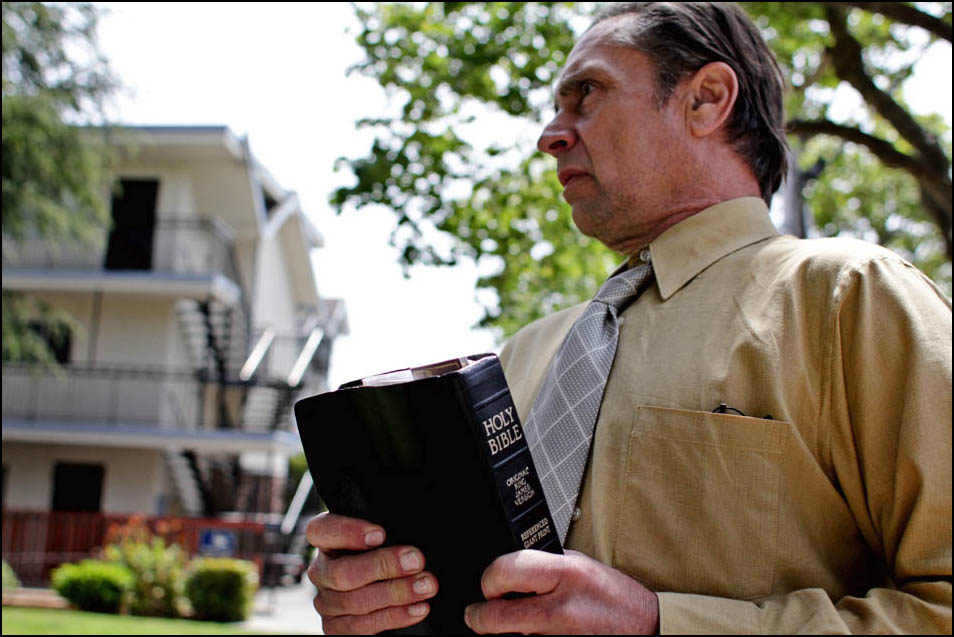

The featured image is of Scott Noble, a member of Camping's

congregation, standing in the empty Family Radio sanctuary

on Sunday, May 22nd. Approximately 2/3 of the photographs

in Pray for Mercy were made before May 21st, and the remaining

third made after. This image fits into the latter third of the

project and brings the whole story to a rather symbolic end.

In the image below, everyone wanted to know what went wrong,

(when the world didn't end) and small groups were huddled together

discussing dates and numerology while flipping through their Bibles.

TID:

How did you manage to gain access to this story?

BRANDON:

After a little research, I discovered that Family Radio and Harold

Camping himself were based nearby in Oakland. That really was

all the prompting I needed. I called up the Family Radio office

and was told I could attend the Sunday morning service and make

photographs. Camping’s congregation was meeting every Sunday

in a rented building, so I showed up for church one morning,

camera in hand. I shot during the entire service and then met and

spoke with people afterwords. The congregation was pretty

ethnically balanced, mostly normal, middle class, and conservative

in nature. Everyone was pretty amiable towards me, even when

I would get up close for shots. In general, my presence was all

but ignored so I kept showing up every week, as well as obtaining

permission to shoot inside their broadcast center.

TID:

What were some of the difficulties you faced, and how did you

handle them?

BRANDON:

This story (literally) had an expiration date on it the moment I

began shooting; There was this certain movement of people

preparing for this certain date. I wasn’t shooting for a school

project, wire, or publication so during the week it was often tough

to draw the line between work and work. There were aspects of

the story I wanted to capture as it unfolded, but simply couldn’t

make myself available. I would say initiative was the other

difficulty.

After a long night out, waking up early on Sunday to go

hear Harold Camping speak for hours was not the most desirable

option.

In all seriousness though, I don’t really have a close group

of photographer friends, so inspiration and initiative has to come

from within during self-assigned projects like this. The images

ended up gaining a lot of attention closer to May 21st, but for the

majority of the project I was just shooting for personal reasons.

TID:

Now, onto the image. Tell us what lead up to the image and how

you handled gaining access to it, and what was going through your

mind at the time.

BRANDON:

On the morning of Sunday the 22nd, it was pretty clear that the

rapture didn’t occur. I decided to pay a visit to Harold Camping’s

home before heading to the church building. I was the first journalist

to speak with Camping after the failed prediction and managed to

snap the image of him rather bewildered outside his home. He told

me that his congregation knew not to show up for church that day

and that there was no service planned. However after leaving his

home, I drove to the church building and found around a dozen

congregation members waiting outside.

I hung out with them for a while, soaking in the mood. Everyone

wanted to know what went wrong, and small groups were huddled

together discussing dates and numerology while flipping through

their Bibles. One of the congregation members angrily told me to

stop making photos and shed some insight on the situation, “what

do you think?” I didn’t mention that I’d just spoken with Camping

himself and as it became clear that he wasn’t coming to explain

himself to his own congregation, I felt some empathy as their moods

slowly turned defeated.

I noticed one of the congregation members Scott trying to get inside

the building. A door was unlocked and I saw him slip in. As much as

I knew he wanted to be alone, I followed him in about 10 feet behind.

He continued into the empty sanctuary and then stood still near the

front. As soon as he stood there, I saw the image in my head. I had no

idea how much time I had to capture the moment but I remember

wanting to make sure I exposed the image perfectly, instead of just

shooting away and hoping for the best. I exposed, focused, and

managed to make one shot before he turned around and walked away.

TID:

Was there any concern about you taking this picture at the time, and

if so, how did you handle it?

BRANDON:

As I mentioned before, people seemed to either accept or dismiss my

presence throughout the project. I knew Scott was trying to come to

terms with the failed prediction and was having a personal moment

inside the sanctuary, but he didn’t seem to acknowledge me as the two

of us stood there in silence. Throughout the project, I tried to train

myself to have a respectful demeanor, without appearing sheepish.

By the time this moment rolled around, I was confident in that approach.

TID:

You mentioned in a previous conversation that you learned a great deal

from this project. What were the lessons learned professionally, and

how did you grow as a person?

BRANDON:

As one of my first “real” photo stories, I learned a great deal while

shooting this project:

I learned that access can be easier to obtain than you think.

I learned that you must have a great deal of personal initiative

when shooting a project independently or on-spec.

I learned that captions are almost as crucial as the images, but a

powerful image may not need a paragraph of text to explain it.

I learned a lot about how to photograph people you don’t know.

All photographers I’ve asked about this have told me it’s something

you have to learn for yourself and I feel. I have grown significantly

in that respect.

I learned that publications still love photographs but don’t like

paying for them anymore.

Importantly, I learned that if you have confidence in the fact that you are

the photographer in a given situation, people generally won’t question that.

In Camping’s congregation no one gave me that title, but I took it the

moment I showed up with a camera slung over my shoulder.

I also think you have a certain degree of amnesty in your actions

as the photographer. I believe this is why it can sometimes be socially

acceptable to make photographs in situations like hospitals, conflict

zones, or during peculiar events such as this. When your subjects have

nothing to be ashamed of, a photographer is usually not seen as a threat.

Therefore I think Camping and his congregation saw no reasonable need

to be weary of me, as they were certain in their convictions.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice (think mentally) do you have for photographers

to gain access to these type of situations?

BRANDON:

Be persistent while also being respectful. People are busy living their lives,

and photographers are often just an accessory (or annoyance) in the context

of something larger. Stake your ground, be friendly, and feel it out. Also

challenge the perspective you take on the stories you shoot. Really think

about what you want to say about a given issue and capture that. Be

articulate with your images.

+++++

Brandon Tauszik was born (1986) in Chicago but raised in England. He spent his late teens and early twenties wandering through the Balkans, learning how to make photos and get into trouble. For two years Brandon then whiled away his hours in the Art & Film department at Invisible Children, a media based non-profit organization. He recently received an Associates in Arts degree, but has no formal education in journalism or documentary photography. Currently Brandon resides in San Francisco where he creates visual media at Sprinkle Lab while assisting Magnum photographer Jim Goldberg.

You can view more of his work here:

http://www.brandontauszik.com/

+++++

Next week on TID, we'll take a look behind this image from David Walter Banks,

a founding member of Luceo Images from The Fourth Wall series:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: [email protected].

For FAQ about the blog see here: