Spotlight on Andrew Burton

Jan 9, 2013

TID:

What an unusual image! When I first saw this I thought immediately this would be perfect to deconstruct. Please tell us a little of the backstory of the image.

ANDREW:

Hi Ross, first, thanks so much for inviting me on - I love this blog - I wish there were more opportunities to learn from photographers about what they were thinking and the stories behind images.

This image was made while on assignment for Getty Images on Christmas Day. I was working the holiday shift, and my editors thought it'd be good to check in on a neighborhood hit hard by Hurricane Sandy. I had covered Hurricane Sandy extensively from late October through early December - from southern New Jersey to Long Island - and I thought the Breezy Point area would be good to look into. It's a neighborhood in the Queens borough of New York, out on the tip of a barrier island near JFK airport. The community is very working class: a lot of police officers and firemen. Some homes have been in the same family for 70+ years. When Hurricane Sandy hit, over 110 houses burned to the ground and countless more were damaged by the rising flood waters.

While the destruction zone is very visually graphic, I knew there wouldn't be many reasons for people to come to that specific area on Christmas Day (the things that were worth recovering were claimed months ago). I knew it would be difficult to find people and an image that said, "Christmas in Breezy Point." But thanks to a bit of luck and a few conversations, I ended up finding this volunteer firefighter who goes by the name Roaddawg (His real name is Edward Manley, but he said he preferred 'Roaddawg - spelled with no spaces, emphasis on the DAWG"). He was decorating a Christmas tree in the affected zone. It seemed to fit perfectly: the wide, burned-out landscape, a Christmas tree, and a grizzled fireman, with a big white beard, wearing a Santa hat, decorating the tree.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot, or what did you do to put yourself in place to make this happen?

ANDREW:

In a strange coincidence, the day before this (December 24) I had met the Breezy Point fire chief of the local fire house in Newtown, Connecticut. I was working with a friend who is a reporter, and we had been covering the shooting at the elementary school. We met the Breezy Point chief at the fire station in Newtown and learned he had driven up to volunteer his time in the community. Here was a man who, just two months before, had physically lost his neighborhood, and he was up volunteering at this other tragedy. I mentioned that I'd be in Breezy Point the next day. He suggested I go and introduce myself to his firefighters at the firehouse in Breezy.

When I arrived in Breezy Point the next day, the first thing I did was go to the fire house. There were just two men working the house - the rest of the firefighters were on call at home. Both men immediately emphasized I meet Roaddawg, a volunteer who had been sent up to volunteer at Breezy Point by his church in Florida. He had arrived two months ago and hadn't left; he was sleeping at the firehouse. They mentioned he had set up a Christmas tree near the burned out zone. So I met Roaddawg, we drove around for a little while, and then he mentioned that in few hours he planned to decorate the tree and put lights on it. We split up for a bit, but sure enough, a few hours later, Roaddawg showed up with his friend Nancy. They said they wanted to bring some joy to the neighborhood and try to make people smile.

I explained I had been tasked with finding, "Christmas in Breezy." They were really nice and understood what I was trying to do. They mostly went about their business and ignored me. At the end of decorating they asked me to take a photo of them in front of the tree, and Roaddawg asked to have his photo taken with me and the reporter I was with.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image and how did you problem solve?

ANDREW:

I think the biggest challenge was simply finding an image that said that, "Christmas was in Breezy." I'm not much of a quote person, but that saying, "luck is where preparation meets opportunity" - it really is true. Had I not gone and introduced myself to the firefighters, had I not spoken to the fire chief the day before, there is a good chance I wouldn't have found this scene. These things come together when you follow your nose, talk to people and listen.

Another problem, though more subtle, is people's media-wariness, media-hesitancy and downright anger towards the media. I've seen it with many stories: Occupy Wall Street, Hurricane Sandy, the Newtown shootings. I totally, completely understand their angst. The media machine, especially the New York version of it, can, at times, feel rather insensitive to its subjects. On any given story in the New York area, there are a lot of media outlets competing with each other, and sometimes it can feel like journalists are willing to twist people's words, or misrepresent them, or exploit people's suffering. I get why people aren't too excited when they see broadcast cameras come out, when photojournalists start snooping around and when reporters with recorders and pads of paper start approaching people. It's something I'm keenly aware of and try desperately not to participate in. The solution is so simple, though: talk to people one-on-one, show them you're a human. Be honest about the story you're trying to convey. Listen to their stories and empathize with them. Remember that it isn't about you.

As a photographer, one rule I often use is not using a 70-200mm. I think the lens can be a bit of a cheat because if you're embarrassed to be there, you can stand so far away from your subject. You don't have to introduce yourself and I think you can come across as a bit of a vulture. I don't like doing that, so on sensitive assignments I try to keep that lens in my bag.

Anyway, as soon as I introduced myself and said, "Hey Roaddawg, I work as a photojournalist, some of the firefighters mentioned you had set up a Christmas tree. Do you mind if I hang around you for a little bit? I'm hoping to find an uplifting image for today from the area," he got it. After that, it was no trouble at all to work with him.

TID:

Now onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

ANDREW:

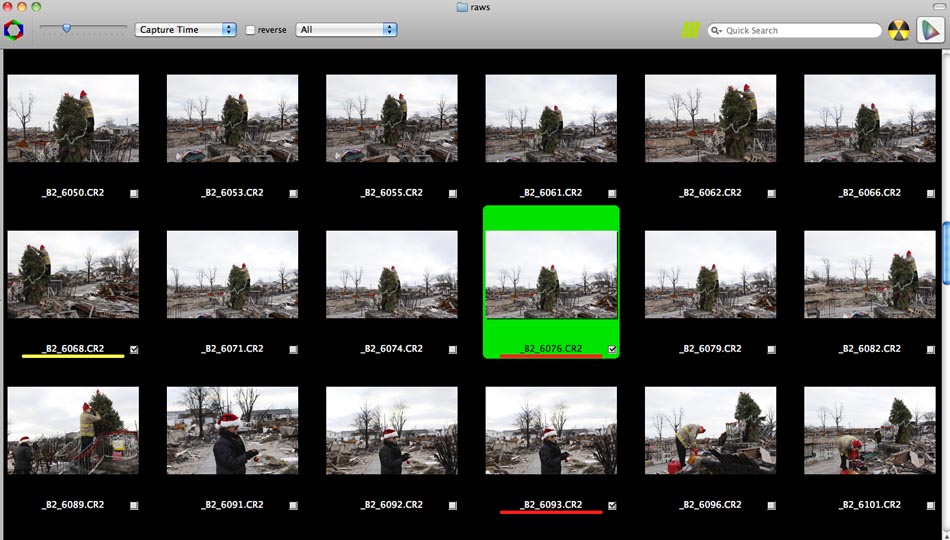

This was a photo that was made due to all the work which came before: meeting the firefighters, meeting Roaddawg, finding the tree, then waiting for it to happen. Once the moment started to unfold, the image was pretty easy to make. I knew I wanted to be pulled back to show the landscape of Breezy Point, I knew I wanted to be as high as possible to show as much terrain as possible. I played around with framing the Christmas tree on the thirds, but liked the symmetry and simplicity of centering the tree. The whole image seemed to sum up everything I was hoping to find.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

ANDREW:

Well, in a very physical sense, I didn't expect Roaddawg to climb up a foot stool (both he and the stool looked pretty wobbly) and put a star on top of the tree. I figured he would just hang a few ornaments. As soon as he climbed up with the star, I knew that that was "the image." It summed it all up perfectly. Other than that, the moment mostly unfolded as I thought it would.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

ANDREW:

The whole assignment reminded me to talk to people, to listening to what they have to say. I think journalists can get a really ugly, useless mindset: that we know what the story is, that we know what we're looking for, and dammit, "Can't all these people get out of my way? I'm trying to find something here..." When in reality, those people are the ones you should be speaking to, listening to, hearing out. Their stories will lead you to the images you're looking for. It's a lesson that's all too easy to forget.

TID:

What have you learned about others?

ANDREW:

I have been reminded once again that for all the negative stories you hear from around the globe, how everything is going to hell in a hand basket, there are real gems of humans out there. For better or for worse, those gems frequently fly under the radar. I'm not sure why that is, but they sure help the world go round. I'm not sure how Roaddawg has been able to stay in Breezy for two months volunteering, I'm not sure what his life was like before the Hurricane, or what it will be after, but the community of Breezy sure knew him, and they were incredibly grateful for him and all he's done - that was abundantly clear.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

ANDREW:

Some of the best advice I've ever been told is that you have to know why you pick up a camera in the morning. Photography is a creative, artistic medium, and by picking up a camera you are inherently displaying that you're trying to express something, show something, say something. But I think a lot of photographers never quite realize what it is they're trying to say or why they pick up a camera - and that comes through in their images. As soon as you can hone in on what it is that makes you take pictures, why you're doing what you do, I think your skill sets get a lot better.

The other piece of advice that I'd give, especially to younger photographers who are still in school, is that it takes time. "It" being your dreams and aspirations and goals and hopes. In the age of Facebook and Twitter and Tumblr and breaking news and one-thousand-and-one contests, it's easy to feel overwhelmed by everyone else, doing everything else, shooting everything else, being recognized by everyone else. At least I felt that pressure when I was a student. It got to the point that I put a big poster over my desk that said, "keep your head down, don't stop producing." I think it's a good ethos to have: hone your craft, figure out who you are, keep shooting and searching and gnawing at your bone. Gnaw at your bone and bury it and dig it back up and gnaw some more. It'll pay off. But you have keep your head down.

:::BIO:::

Andrew Burton is a freelance photojournalist and multimedia producer based in New York. He has a degree in journalism with a focus in photography from Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications.

Prior to becoming a photographer Burton interned at Getty Images, The Oregonian, Bloomberg News and The (Syracuse) Post-Standard. He was also an assistant to Vincent Laforet and completed a fellowship with the Carnegie and Knight Foundation. His work has been honored with awards from Photographer of the Year, International (POYi), the Hearst Foundation, Society of Professional Journalists, College Photographer of the Year and the Oregon Newspaper Publisher’s Association.

He was a student at Eddie Adams XXII and has also been selected for private workshops at VII Photo Agency, and the 7th UNESCO Youth Conference. Beyond his education and work experience, he has lived in New York City, Sydney, London and Portland, OR. He minored in international politics and economics.