Spotlight on A.J. Chavar

Oct 23, 2012

TID:

AJ! Thanks so much for being a part of this. You're our first video TID interview. Please set the stage and tell us a little of the backstory.

AJ:

First of Ross, thanks for having me--it's an honor to be featured among so many of the great visual thinkers who I look to for inspiration!

The idea for this video actually came to me quite a while before the political conventions. I forget the exact timeframe, but six weeks before the RNC sounds about right. The Washington Post video staff was tasked with developing ideas for more politically focused videos and I already knew that I was being sent to both conventions. I was in a place with my own work where I felt I could tell a story, and I felt I could shoot well, but didn't feel like I had put those skills together. At the same time, I was really loving the work done by video outfits like Everynone and California is a Place. I wanted to bring that sensibility to my work in newspaper video.

The main inspiration came from Everynone's video "Symmetry," except that I wanted to push their concept in a few key ways. First, as a journalist, I couldn't set up any of my shots; second, I wanted to tell a slightly more distinct, linear story; and third, I wanted to make near-direct comparisons between the DNC and the RNC.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot, or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

AJ:

I try to pre-plan, or at least pre-visualize every shoot that I do, but this was a very different monster. I hadn't ever shot the national political conventions and really all I could ascertain about being on the ground was that it would be hectic. For that reason, a lot of the prep I did was technical, so that I'd (hopefully) only have to worry about the mood and content while shooting.

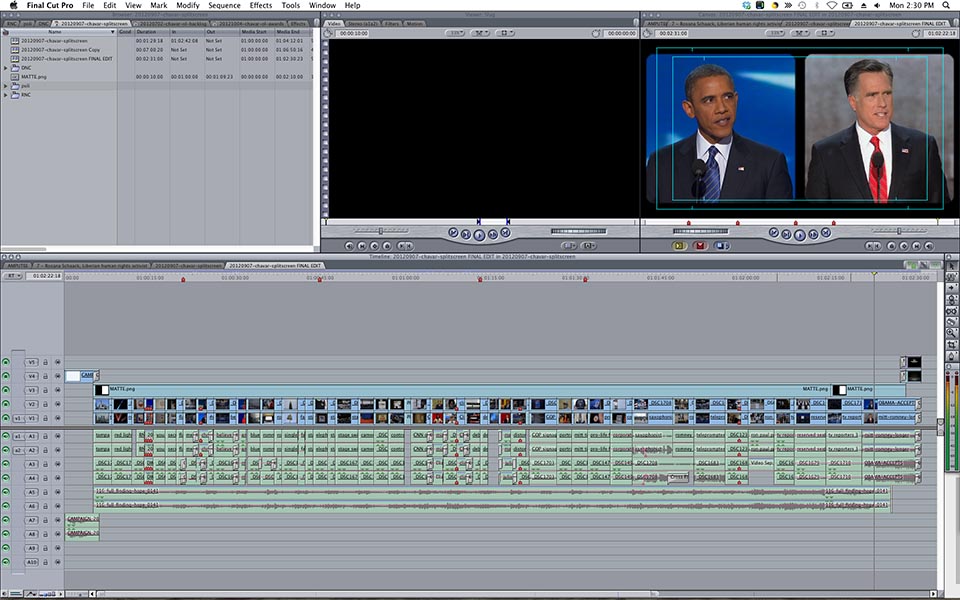

A few weeks before the RNC started I picked out a piece of music that I was going to set the piece to. I set up a template in Final Cut Pro with our intro animation and credit slides and listened to the music straight through several times. After a few times through, I listened with my finger on the "M" key, adding in marker points every time I felt a beat in the music I could potentially cut the visuals to. I also created an overlay in Photoshop that would split the screen in two. I was hoping to have a complete shot sheet done before getting to Tampa, but my unfamiliarity with the scene on the ground led me to only having about 10 shots I knew I wanted before I started shooting.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this video?

AJ:

The biggest challenge was making time during my assigned projects to capture what I needed for this. We were very focused with day-to-day video, as that's what visitors who go to our website are looking for. This was compounded by Hurricane Isaac, which took a fellow videojournalist out of the picture when she went to New Orleans for that story. It was occasionally hard to convince my boss that I needed an hour or two to go shoot for a project that wouldn't been seen for two weeks when I needed to get about two videos done per day. I was stressed out that I had proposed this big project that I wouldn't be able to finish, or even worse, adequately start. Even more worrying to me was my short shot list, and with the daily drain on my energy I was having a hard time visualizing the full piece. My biggest fear was that I would fail to return on the promise I made for this video and wouldn't be trusted when I proposed other things in the future.

TID:

Can you talk more about what it mentally takes to push for non-linear, thematic storytelling in today's current daily newspaper setting?

AJ:

I'll answer this as best I can because I think there are two parts to it: what you need to do for yourself, and what you need to accomplish within a newspaper.

For yourself, you have to want to play. Experiment and make mistakes, learn from mistakes, and make different mistakes. When I say play, I mean genuinely have fun with what you are doing, and push yourself. Pose a question to yourself about a technique in shooting or editing, and see if you can answer it, by doing or by learning about it.

Going out and shooting too, without a specific mission or goal in mind is great. It relaxes your mind and you try weird stuff with your camera settings, your compositions, your editing techniques. Those little pieces in and of themselves aren't much, but when you apply them to a project or a body of work, you start seeing all the avenues you can take your work down. It's limitless. Exposing yourself to a variety of visual media is also essential. There are ideas everywhere, so it is important to expose yourself to as much as you can. If you only consume news media, documentary video and news video, you get backed into a corner when thinking about what a visual story is. But when you have all of this other art and visual storytelling to look at you open up to the possibilities.

As far as doing this within a newspaper... that is a much more difficult question. For one, you need to be able to talk about your work and explain why your (non-traditional) storytelling idea will work better than a traditional narrative for your project. You can't be doing something just to do it. I think in general, visual editors welcome these ideas, as long as you can effectively back them up. You also need to be open to collaboration and feedback. I am not the best at taking feedback on projects that I am passionate about because I feel that I have a better understanding than anyone else does. But you know what? That doesn't matter. The feedback that you get is essential BECAUSE it comes from someone not as familiar or passionate about your work as you are.

Lastly, you need to know how to juggle assignments. Because of the way the news cycle is at a daily, I am almost always working on two things at once, normally a longer term, or bigger project, and a smaller series, or a daily video. If you have a project that you want to be out of the box with, just expect that you'll have to do it while filing your regular assignments as well. You need to manage your time and you may need to convince an editor that you need more time for one project than you were budgeted. But you can't look at one project as being more or less important than another--pushing yourself when working on that daily video can often give you an idea for your pet project, or just let your mind see a problem in a different light.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems? (Problems are not unique, but what is unique is a photographer's ability to problem solve.)

AJ:

In this instance the best medicine was just forcing myself to get out there and shoot as much as possible. While I was on one assignment, if I spied a shot I wanted I'd either take a break and grab it or write it on my hand to approach later. At one point during both conventions I had lists of 20+ shots written on the back of my hand. This became easier at the DNC - during my "break" between the conventions I laid out a rough edit to the music of all of the shots I wanted to use from the RNC. This let me basically do a "fill in the blank" while I was shooting at the DNC. I could see my timeline get a little fuller every time I came back to edit, and that visual progress bar kept me going. It gave me a solid reminder of everything I still needed to do. I like the idea of editing and shooting simultaneously - that's actually advice I give for shooting a video on a tight deadline, edit mentally as you shoot. In this case I was actually editing the video and that gave me a very clear purpose every time I went back in the field.

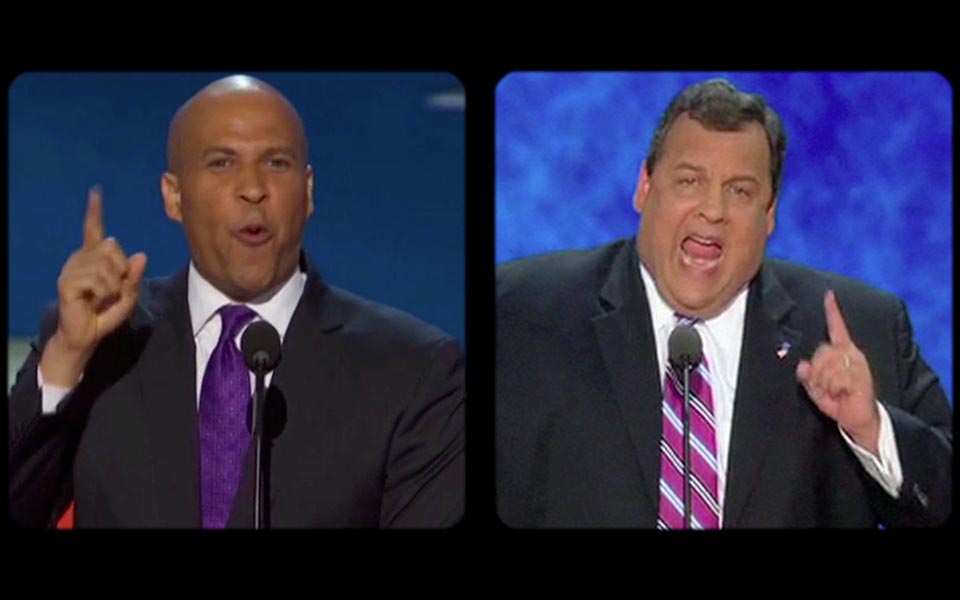

And then there are the problems you don't expect. One interesting turn was when I showed a rough draft to my editor. He liked it, but his first response was that it was quite literally, too black and white. Essentially, the Democratic convention came off as looking very diverse and the Republican convention looked like all old white men. Yes, the party bases do skew in those directions, but it's not the whole truth. Initially, I was too stubborn to change it, but I realized it wouldn't be fair to generalize in the way I had, even if it was unintentional. To solve that problem we spliced in more shots of the speakers. Jayne Orenstein found the best shots and synced together their body language.

TID:

Now, onto the video. I think this is so refreshing. Can you talk about how this strikes a different chord than most videos done at newspapers?

AJ:

A lot of people have made that same comment, that this isn't what they expect to see from a newspaper, and it makes me sad that they're right. The majority of the work I do isn't getting to be nearly as creative or freeform as this project, but in my experience so far, this has had more traction than any straightforward two-minute feature I've done. Overall, I really feel that there is a place in newspapers for non-linear, thematic storytelling.

I very deeply wanted this project to be different. I wanted to touch on a lot of things in one video, and from the beginning it was important to me that the end product be something that people would inherently want to show other people - not just for my own vanity but because we share things that make us feel something. Be it good or bad, you're not going to share something you just feel "ok" about. So that goal was both personal and professional, I wanted to succeed in creating something people were moved to share, and obviously page views are a big part of a journalist's reality these days, so sharing also meant more views. Video is still in its infancy at newspapers, even at the Post, and I kind of thought to myself, I can't do something out of the box without some sort of concrete payoff to show that this type of storytelling has a place at a newspaper. I'm absolutely sure I was being paranoid in that regard, because the environment here is very open to trying new things, but I had a fear that the end product might only be important to me.

I think a lot of the great visual work created for the web at newspapers is very literal - including my own. I'm not sure why this is, because great reporting and news storytelling don't need to be literal, just factual. I've seen great concept photo essays go to print AND run online, but it seems that most work created specifically for web consumption is literal. Short and literal. What made me very happy about this project when it ran was that the comments section on our website ran the gamut from people claiming it was biased in favor of Democrats and others swearing I was under the influence of the Republicans. That let me know that this was both unbiased and open enough to interpretation.

TID:

What surprised you about making the video?

AJ:

A few things. Because of all the planning I put in, the final product came together surprisingly quick despite my fears all along the way. The video was in the process of uploading to our website before President Obama had finished his convention speech. I wasn't expecting to be done that early, but I was quite happy it worked out that way.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making this?

AJ:

This was probably the most ambitious project I've undertaken thus far, but the interesting thing is now that it's in the rearview mirror, it doesn't seem like it was ever that difficult. I think I've learned I need to stop worrying about "what-ifs" and get out there and start doing; it became a lot easier when the deadline, my other assignments, and my own drive just pushed me out there to work.

TID:

In general, what do you think you now know to better present information/content in a media-saturated world?

AJ:

When I went to school for photography, I had been shooting in high school for three years. I knew just enough to know I knew nothing (but I acted like I knew everything). My first semester at university working for the campus daily, I learned more than I had in the past three years. My first year out of school, I learned more about videojournalism than university and internships had taught me in four. I'm still learning a ton every time I go out and try to tell a story. The most important thing I know now is that there is always more to know. The more I learn about art, video, photography and most importantly, the world around me, the more I can apply that to stories I care about.

I'm not sure exactly what I know about presenting my work in a media-saturated environment, but in my experience, you can't keep good stories, or beautiful work, from getting out there. You might need to push and prod, or more likely, tweet and poke, but the upside of presenting visual work right now is that the internet is a visceral and visual place. Comparatively few new online experiences are being catered towards reading, and more and more focus on visuals and design. I think as we move forward, visual journalists will have the upper hand in digital publication. Writing has ruled the printed news for a long time, but the web is about seeing.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers/videographers in making things that are progressive like this?

AJ:

My best advice would be to just go out there and try, even if you fail. And also, don't be afraid to stand up for your work. I was nervous about the amount of "play" this would get on our website, because the experimental nature of the project meant that there wasn't anything necessarily set aside for it. I had this fear that I would have worked so hard for those two weeks and the video would just get buried under all of our other more straightforward coverage. But I stood behind it with my editors, and took it to the producers who control our homepage. Because I invited them over to watch the draft, listened to and heeded their input, they ended up being the ones who pushed for the placement of this video on our homepage for two days. Not me. It took me standing behind it initially, but it was really humbling to see other people carry my work forward.

:::BIO:::

AJ Chavar is a staff videojournalist at The Washington Post, who focuses on innovative storytelling through multimedia. His work has been recognized with a Virginia Press award, local Emmy nominations and wins, and a National Edward R. Murrow award. Before joining the Post, AJ was a student at Syracuse University's Newhouse School, studying Photojournalism, Religion, and Information Science. In 2010 AJ was a Carnegie-Knight News 21 fellow, participating in Syracuse University's "Apart From War" long form documentary program studying the effects of war on veterans and their communities. Behind a camera, AJ is happiest telling stories about people and science. When he's not shooting, he's happiest being in nature, spending time with his girlfriend, or both.

You can view more of his work here: