C. Aluka Berry

Jul 17, 2012

TID:

This is a really interesting image, please tell us the story behind it.

ALUKA:

First of all, let me thank you for inviting me to be a part of this blog. I think this is a great resource for photographers and I feel honored

to be included.

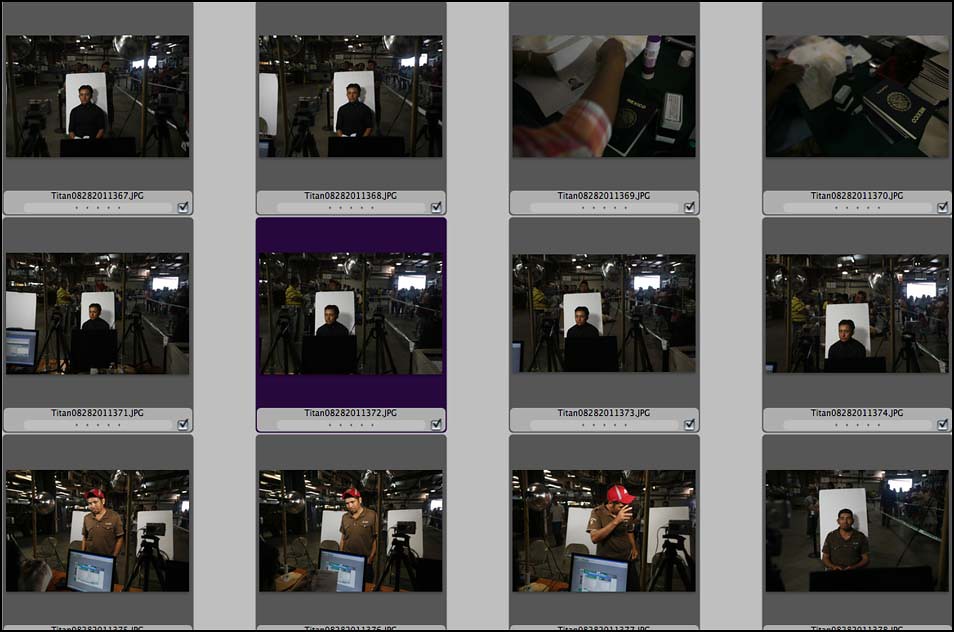

In this photo, Fernando Haro, 19, waits to have his picture taken in order to receive a matricula I.D. card. At the time I made this photo, I had been working on a project for over a year documenting the lives of Mexican migrant workers at Titan Farms in Ridge Spring, S.C. I received a phone call from my contact, informing me that the Mexican Consulate was going to visit Titan Farms in order to issue matricula cards. These cards provide Mexican workers with legal identification that can be used to open bank accounts and obtain U.S. driver’s licenses.

TID:

Since this part of a larger project, can you now talk about the project, and why you're working on it.

ALUKA:

Every year, more than four hundred Mexican men and women travel approximately 1800 miles in order to work at Titan Farms for up

to ten months at a time. As the second largest producer of peaches in the U.S., Titan offers the Mexican farmers work, transportation,

and group housing. What they make in one year at Titan is equivalent to what they would earn in three years working an agricultural job

in Mexico.

I was attracted to this project for several reasons. I have always been drawn to stories that focus on various minority populations,

as they are often underrepresented in the media. When I first visited Titan Farms, I was intrigued by the community living I encountered

there. Men and women live in separate homes, with 3-4 per bedroom and about 40 people residing in each house. Because this lies in

such stark contrast to the way I live, it was something that I wanted to explore further. My biggest impetus for wanting to do this project is a desire to dispel negative stereotypes about immigrants. I especially wanted to confront the belief that the majority of Hispanic agricultural workers in the U.S. are working here illegally.

TID:

Can you talk about gaining access to this project? How you manage to do this?

ALUKA:

Several years ago, I was on a daily newspaper assignment to photograph Titan Farms, which had lost a large portion of its crop

due to a late frost. The farm manager, Amancio Palma, and I really hit it off; he took me on a tour around the farm grounds and explained the

symbiotic relationship that exists between the farm and its workers. At the end of our visit, I asked Amancio if I could come back some time

and live with the men in order to tell their story. He was excited about this idea and offered to help in any way he could. After this meeting,

Amancio spoke with the workers about my interest in the farm and their way of life there. He emphasized the beneficence of my

intentions and that I could be trusted.

Despite Amancio’s introduction, I still had to prove that I was indeed trustworthy, respectful, and had good intentions. The fact that I speak very little Spanish and that most of the workers do not speak any English made verbal communication somewhat difficult. Therefore, I had to be cognizant of my body language (make eye contact and smile often) as well as maintain an awareness of their nonverbal signs.

If anyone offered me a drink or food, I always took it. The only thing I said, “No, gracias” to was tequila, which I can not handle

as well as I could in my 20s! Additionally, living with the guys and spending time with them at their homes, in the fields, and at fiestas and

barbecues further emboldened the trusting relationship necessary to gain the access I needed.

TID:

What are some differences between the women and the men that you found during this project?

ALUKA:

There was definitely a contrast between my experiences in photographing the men versus the women. When I photographed the men,

I stayed in one of the community houses with them. When I photographed the women, I slept in my car near their home. The biggest

difference that I observed was that the men didn’t really care about how they appeared on camera or if their rooms looked tidy. The women,

however, wanted to make sure that their living quarters were clean and that they looked nice for the camera. Early on, I requested that they

not change anything about their room or themselves because of my presence, but it took some time before they actually felt comfortable doing so. Additionally, it was more challenging to get photos of the women naturally, because they would often pose for the camera.

Another difference between the men and the women was how much more open, informative, and inviting the women acted towards me. The

women were much more likely to tell me about their personal lives and to invite me to go to birthday parties, the dance hall, and other places

with them in their time off work. With the men, I had to ask more questions, as they were not prone to offering information without request. Also,

the men did not invite me to go places with them, as the women had done. Although both genders were very friendly and kind, the women

definitely were more verbally expressive and affectionate; they even offered back massages to one another after a hard day’s work!

TID:

Now, back to the lead image. What challenges did you encounter while working to make it?

ALUKA:

The first challenge I encountered was just getting to the farm that morning. The night before, I had been celebrating with my brother

at his bachelor party in another city. So, after only three hours of sleep, and on my day off work, I had to drive 1½ hours to the Farm so that

I could be there by 7:30 am that morning. Once I arrived at the Farm, I was surprised to see hundreds of Mexicans who were not Titan employees. Since my project was documenting the lives of Titan Farm workers, my second challenge was to stay focused on shooting them and not the hundreds of other people there.

I had been photographing people for several hours before moving on to capture individuals getting their pictures taken for matricula I.D. cards.

It was at this point that I encountered the challenge of finding a composition that worked.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

ALUKA:

In terms of getting to the farm and shooting on my day off with little sleep, I just had to dig deep to find my motivation for doing the story

and tell myself to keep pushing. “Keep pushing” was a sort of mantra that I used throughout the time that I worked on this project. Whether

it was sweating in the fields or dealing with the struggles of not speaking Spanish, I always told myself, “Keep pushing!” I tried not to be

distracted by the hundreds of people at the matricula I.D. card event, so I chose a group of workers with whom I was personally familiar and

followed them through the process.

I photographed from multiple angles and at different focal lengths, played with my exposures, and prepared myself so that I was ready

to capture a moment when it presented itself.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

ALUKA:

I had photographed about ten people as they went through the line, getting their pictures taken. I really liked the

way the small white background boards made the subjects in front of them ‘pop.’ I had shot a few frames with both of the white boards in

the background, but then decided to just focus on one of them.

Once Fernando sat down to get his I.D. photo taken, I noticed the way his black shirt created a stark contrast with the white board background.

As I was photographing him, his eyes raised and he stared directly into my lens. Normally, I do not take photos of people looking straight into

the camera unless I am making a portrait of them. However, I have encountered situations like this one before and found that, sometimes, this

type of photo does work. So, I took a chance, hoping this would be another one of those times.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment/project?

ALUKA:

What surprised me about capturing this moment was that his direct eye contact gave the photo an energy that all the other images I made

that day lacked. One thing that really surprised me about doing the project was that, despite an immense language barrier, the workers and

I were still able to communicate and, more importantly, connect with one another on a personal level. A pleasant surprise that came from going

to document the lives of the workers was the friendships I made as a result.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this? What have you learned about others?

ALUKA:

What I learned about myself is what I am constantly learning: to follow my intuition, to keep pushing despite challenges, and to

take chances. As a result of this project, I developed a greater understanding of and appreciation for the Mexican heritage and culture.

I also am more aware of and thankful for the hard labor and sacrifices that are made by agricultural workers so that we all can have

food to eat.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

ALUKA:

If you feel that there is a story that needs to be told, you must be willing to make the sacrifices necessary in order to make it happen. When

I started this project, I wanted to document the men for a peach-growing season and then stay with the women for the next growing season.

However, the newspaper was unable to provide me with the time to photograph the women at Titan. So, I made the decision to complete this

project on my own time. It was a challenge to make it happen in between work, school, and personal time, but it was well worth the effort.

Also, I would like to pass on advice that was once given to me by a friend: remember to have fun and stay positive!

:::BIO:::

C. Aluka Berry was born in Chicago, IL, to an Irish American mother and African American father. In hopes of escaping the “rat race” of the big city life, his family migrated to South Carolina when he was a young boy. As a teenager, Aluka found that he had a passion for stealing souls. After working as an appliance salesman and later, as a mortgage consultant, he became a freelance photographer in 1999. Some of his clients included The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, The Charlotte Observer, and The State Newspaper. In 2005, he was hired as a staff photographer at The State, the largest newspaper in South Carolina. Since then, Aluka has won the Judson Chapman Community Journalism Award, Ambrose G. Hampton Award for Outstanding Photojournalism and has been named the South Carolina Press Photographer of the Year three times. His work has also been recognized by the National Press Photographer’s Association, Editor & Publisher, Southern Short Course, and Society for News Design.

You can view his work here:

If you have suggestions of an image you'd like deconstructed, or if you wanted to be a guest interviewer of someone, please contact: