Spotlight on Rebecca Drobis

Feb 6, 2014

TID: Please tell us about the image's context and background

Rebecca: This photograph was made in the rural community of Heart Butte, Montana, on the Blackfeet Reservation. The remote community is hard to access, and the residents aren’t used to visitors. It has taken years to earn their trust and gain access to their community, and I did that by returning again and again to Heart Butte with photographs from previous visits.. It took me four years just to gain the type of access that I wanted and to begin shooting what had inspired me initially. I wanted this project to be intimate. Any parent is going to be protective of their children, and I respect a child’s right to just live and be private. Also, I respect a community’s right to exist without somebody poking and prodding at it from the outside. I wanted to capture the community from within it and not just from the window of the car or walking around on the street. Those first four years allowed me to engage with my subjects and ask proper permission to capture moments of their lives.

I did everything possible to make sure everyone understood that I wanted this to be collaboration. But it took time to build up that trust. I didn’t specifically get permission from the tribal government or any type of official authorities besides the parents, guardians and educators connected with the children I was shooting at the time. First, one or two families came to trust me, and then the word spread out that this girl is OK. I keep coming back, and I bring pictures with me and show them. This lets them know what is happening with the project and lets them contribute to it. I built trust by returning again and again; I had to show that I was truly committed for the long-term.

TID: Can you explain what kinds of conversations you’ve had with people to gain trust? how have you gone about that?

Rebecca: When I am shooting on the street or in public places, I have always worked with volunteer members of the community who believe in my project and are willing to accompany me while I am shooting. These liaisons bridge the gap between me as an outsider and members of the local community, which is especially critical when I am photographing children or minors. I will always attempt to seek out the parents or guardians to ensure their willingness, as I do not want to photograph anyone without explicit adult permission.

Surprisingly, I have never been turned down or asked to leave. I credit this to having community assistance, support and trust that I built up over time. Whenever I have done any type of street shooting, I have always been with a member of the community, which has served as an important bridge. At this point, I know so many people and have photographed so many different families, that I get recognized as “that white lady with a camera."

To my knowledge, I don’t think there is a specific expectation from the community or families other than to uphold my word as stated. I always bring back or send prints, which really is important to me. I’ve found that it is important to them too.

I have gotten some great reaction to the body of work. The most important opinions are those of my subjects and their parents. I am very grateful for this trust and want to make sure to portray their lives accurately.

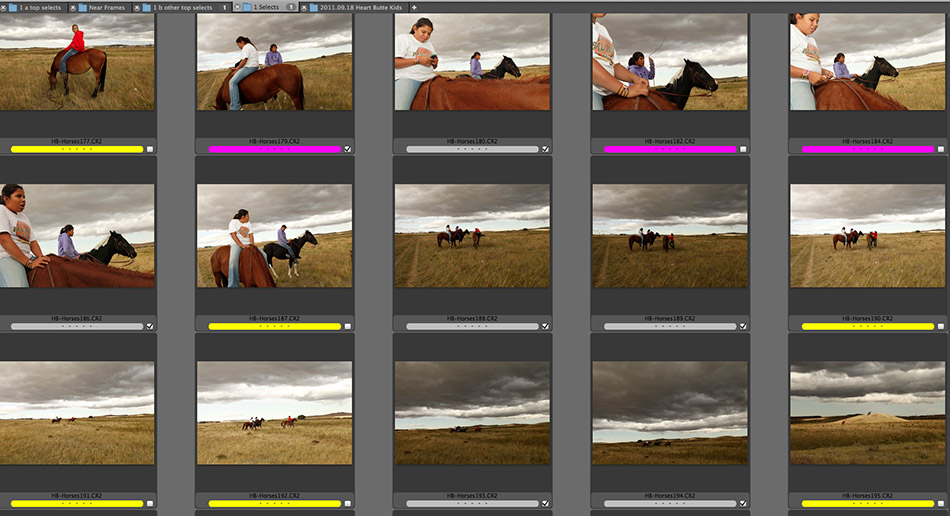

Rebecca: In 2013, I refined my shooting-style; rather than shooting many different subjects, I committed to telling more in-depth narratives of a few key subjects and families. I am very excited about the progression, as I am now more connected with my subjects and feel like my newer work reflects this intimacy.

I chose to photograph the children on the afternoon of their first day of the school year, in hopes of catching their excitement. Many of the students ride their horses bareback to and from school;, and on this particular afternoon, they converged at the playground in the center of town. They were racing each other, flying down the streets. It was really impressive, and I was shooting like crazy. I had a good set of shots and felt like I had put in a productive day. Then these clouds starting rolling in from the east, and the sky and light got dramatic. I knew I had to stay and shoot more, but unfortunately the children had all disappeared.

Rebecca: I ventured around for a while and shot some landscapes. The wind was picking up and people were scarce, so I thought about wrapping up. Out of nowhere, three of the girls who I had photographed earlier rode back towards me on their way home. At this point I had already spent 2 hours chatting with them and shooting video of their horse races. They were eager to watch themselves on the tiny screen on the back of my camera., At this point I felt that they trusted me, and they were comfortable giggling about boys and school with me. One of the girls pulled out her cell phone and started texting her boyfriend.

Rebecca: There was something really strikingly familiar, yet visually exciting for me in this moment as a photographer. All adolescents are constantly texting each other—it is universal. But this young woman was as at ease on the horse as she might have been sprawled across her twin bed at home, in a private moment, caught in a daydream.

TID: You mentioned the first day of school being a catalyst for this image - How do you usually approach photographing this project? Do you find people and then hang out with them? Do you pick a place and wait until folks enter, then try to discuss what you are doing with them?

Rebecca: I have been shooting on the Blackfeet Reservation for many years, so I have covered many of the larger public events like the annual Pow Wows, Blackfeet Rodeos, parades and other public festivals. As this project continues over time, I am challenged to find new situations to document. I had a tendency to reshoot the same things over and over again—like children playing. I probably have thousands of photos of kids jumping on trampolines, because I love shooting kids outdoors.

Rebecca: Thanks to some harsh peer reviews and feedback, I realized that I needed to branch out, to show diverse aspects of life on the reservation. This photo resulted from my efforts at expanding my photography.

TID: Was there anything that you learned or put to use in later assignments that come about from this experience?

Rebecca: I learned that sometimes the quiet moments can be the ones that have the most impact. I took advantage of the relationship and trust gained with these girls earlier, as it allowed me to capture this intimate moment. I am thankful that I stuck around after I thought I was finished.

Rebecca: This was also a turning point for my larger project. When I started shooting on the Blackfeet Reservation in 2003, I was drawn in by the striking visual differences between how kids were living on the reservation compared to my own childhood in more mainstream America. This photograph – this moment - shifted my focus towards the similarities between the two. . I find that children in Montana have well developed physical strength; they have confidence that comes from riding bikes through their small town, from exploring the woods and surrounding forests, and from spending weekday afternoons sledding in sub-zero temperatures. Ideally, I would like the viewer to see what they have in common with people from the Blackfeet Reservation -- to dispel the notion that Indian reservations are “outside” of mainstream America. Kids are kids: they are willful, resilient and possess the inspiring ability to be fully present in the moment.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

Portrait photographer Rebecca Drobis tells stories through her work. She focuses on childhood, teens, and communities, exploring the world through each person’s point of view.

www.rebeccadrobis.com

New Stories GROWN UP WEST: http://www.grownupwest.com

Honored by the American Society of Media Photographers Best of 2013: http://asmp.org/best-2013-drobis