Spotlight on Niko J Kallianiotis

Aug 26, 2013

TID:

What a pretty and subtle image. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

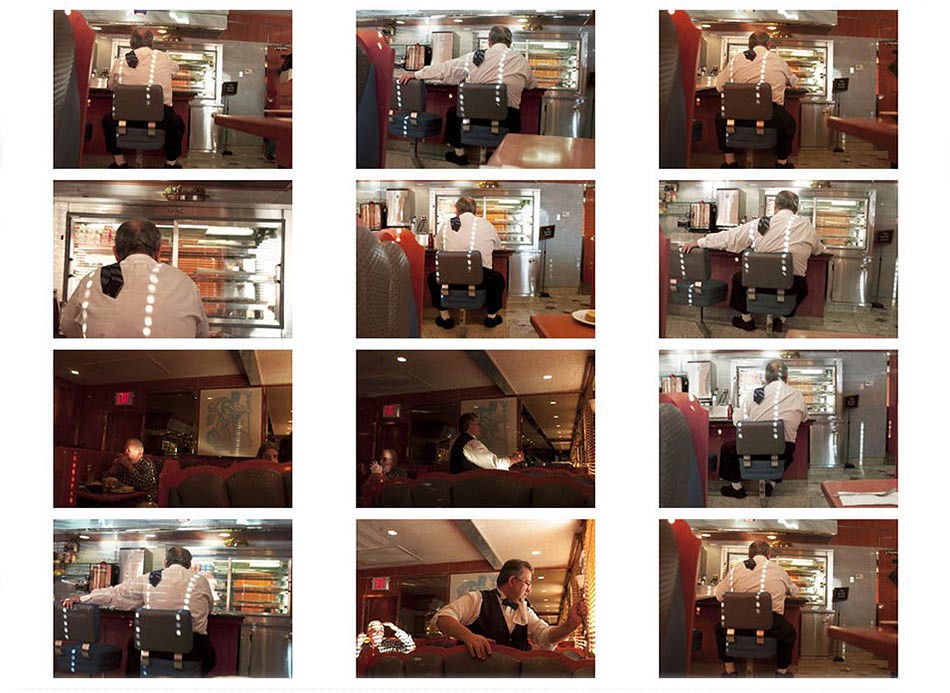

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to present my work on this blog. This is one of my first images from my project Pikroglykimalon: Bittersweet Apple, which I started in 2011 and it’s about my return to Astoria after twenty-five-years. This image was taken in the heart of the Greek community in one of the most historic Greek diners in Astoria, Neptune. I used to go there frequently with my family in the early years after my arrival from Athens, and this diner was very distinct in my memory. The decision to make it one of my first stops was utterly organic. I was mostly looking to get some information and make some contacts within the Greek community that could help me define the possible parameters of my project, and was happy the outcome of my visit was compelling.

TID:

This is part of a larger body of work - can you tell us about that work, and where this fits in with it?

NIKO:

For Pikroglykimalon: Bittersweet Apple, I wanted to investigate the Greek-American diaspora and its survival in images that depict the symbols and explore the cultural traditions and memories in this diverse setting that was once the center of Hellenism in North America. My goal was not to make a survey of the Greek symbols, traditions, and characters, but rather to make it a personal journey. I was looking for images that depicted my alienation and eagerness to discover some sort of tranquility, in a place that once felt so foreign. As a youngster, I resented being in Astoria. During my adolescence, I often tried to find ways to escape and return to Greece because everything and everyone in Astoria felt foreign to me, even the people that shared my own heritage.

I felt a powerful sense of disconnection; I missed my friends, my extended family, my neighborhood in Athens, everything. What I expected to be familiar during my first visit to the States as a child was actually quite unfamiliar, regardless of the reminders of Greek culture that Astoria offered. That environment, its diversity, even the faces I encountered in the community, only added to my sense of alienation. There were Greeks here, but they were not “my” Greeks. I believe this image set the tone for my approach and I was fortunate that it came early in the process. Literally, this was one of my first takes.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot/project, or what did you do to put yourself in place to make this happen?

NIKO:

I have been an editorial photographer for about fourteen years and this was my first large-scale personal project. I had to work with a different set of ideas for this project, and above all this was something that was not assigned. This was a personal encounter, it was my journey from the past, my experiences and my memories, what I remembered and what I didn’t want to recall. I had to reconcile and prepare for this transition and I must say the process at times seemed incongruous. On occasion, it was humorous because I said to myself, you have years of experience and stylistically you will work with the same visual criterions and approach, therefore this shouldn’t be such an issue. Little did I know.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter and how did you overcome them?

NIKO:

I was born and raised in Greece and I speak the language fluently. My work as a photojournalist leads me to believe that my communications skills are solid. With that in mind I thought it wouldn’t be hard for me to get into the Greek homes and photograph the nuances of culture and traditions. I had no contacts in Astoria and I knew I had to knock on doors and talk to people on the street. I was thoroughly comfortable doing this and I did to a great extent. I went on online forums, made phone calls, talked to people on the street, but with little luck. Surprisingly, although I live in Astoria and speak the language fluently, I wasn’t able to accomplish that.

At times I wondered about the reasons. Maybe it was because in our current society in a metropolitan city, people do not let strangers into their homes easily, especially if he's holding a camera and explaining his project and his alienation. But I was Greek, and to me that didn’t always make sense. This resulted in concentrating predominately on the street, and always pondering the idea of entering the interior. On occasion, I did manage to get inside. That and avoiding making it superficial by showing trays of spanakopita and juicy gyros were some of the things I needed to overcome.

TID:

Now, on to the moment. Can you talk about the circumstances leading up to the moment?

NIKO:

I visited Neptune diner one late afternoon and sat in one of the booths overlooking Astoria Blvd. I started observing the space since I haven’t been there in two decades. While walking there thoughts of confidence conquered me. I was thinking, I could definitely make some contacts there since this was after all a historic Greek diner. It was an interesting experience because the patrons were from diverse ethnic backgrounds. Astoria has changed rapidly in the last years with hundreds of ethnicities, compared to the Greek, Italian and Irish heritage that dominated the neighborhood in the 80’s, and I found that fascinating.

That characteristic and the light Greek décor made my visit more interesting. I still wanted to capture the Greek element, but I wanted to deviate from photographing the mural depicting Poseidon. There was not much going on, but I kept looking. I started photographing some patrons and servers from my booth, trying to incorporate elements of my presence. But still, something was missing.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment that you weren't expecting?

NIKO:

The light that plummeted into the dining room was divine with hues that sent me traveling to the Mediterranean islands, and with Poseidon overlooking me things were starting to fall into place. The space was starting to be quiet and serene and I was longing for something special. The light coming though the blinds was creating an interesting design falling on the counter. The problem was that there were no people.

I was about to leave and the man depicted in the photo sat on the counter. His statue-like posture with the tie flipped on his back instantly brought specific words to my mind. This is totally Greek, I said to myself, and with the Poseidon mural to the right it made a unique contrast. His stance with his back towards me, myself observing him in conjunction with the “This Section Closed” sign to the left, translated and initiated my goal for this project. To try and open any “closed sections” that reinforced my sense of alienation. For a moment, I was reflected in him, and possibly he was reflected in me.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

NIKO:

To look beyond the ordinary; to be patient and always look for the nuances which make our environs visually dynamic. This image helped me improve in the way I look and see, but most importantly confirmed the notion I always carry with me. That is to concentrate on the unexpected, on elements that don’t always co-exist in a photograph but when they do they send the viewer and the photographer on to a different journey. I would like to add one of my favorite quotes from Garry Winogrand: “There is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described.”

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

NIKO:

Make it personal. I can’t overstate how important this is to my work and I am a firm believer that it should be the canon for every photographer. Photograph something you care about, something that moves your heart because if you don’t have the connection, you will not be able to transcend the viewer in the photograph and your work. Photographers fall into the trap of photographing subject matter that “sell” or are popular in order to break into the trend. I don’t necessarily subscribe to that but if that is the direction a photographer wants to take, fine. But make it personal. It must be something you care and feel strongly about and find that angle that will make it unique.

When I look at a photograph I want to first feel the photographer’s connection with the subject matter, because if I don’t the image will be lost among the million of images on Flickr. Make it personal and shoot from your heart and by doing so all the obstacles that come along the way will organically be overcome and vision and photograph will become harmonious. Show me something that I will remember. Don’t show me what you see, show me how you feel.

::::BIO:::

Niko J. Kallianiotis was born in Kozani, Greece, in 1973 and grew up in Athens. In 1997 he moved to the United States. In Scranton, Pennsylvania he completed his B.F.A. and he also holds a M.A. in photography from Marywood University and MFA from the School of Visual Arts, in Photography,Video and Related Media. He started his career as a newspaper photographer, first as a freelancer at The Times Leader, in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and then as a staff photographer at The Coshocton Tribune in Coshocton Ohio, and The Watertown Daily Times in Watertown New York. At the moment he is an Assistant Professor of Photography at Marywood University in Scranton, Pa. and a freelance photographer for The New York Times.

Originally from Greece, he tries to investigate and assimilate in the communities he resides, both in Pennsylvania and New York, by concentrating primarily on street, documentary and portrait photography. His work has been published and exhibited nationally and internationally.

You can see more of his work here:

NYT Lens Blog Link: http://tinyurl.com/mk8t9gw

Website. www.nikokallianiotis.com