Spotlight on Nicole Fruge

Aug 21, 2012

TID:

Hey Nicole, thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts. Would you start by telling us how you got started with conflict photography?

NICOLE:

On September 11, 2001, I was in the local pool covering George W. Bush’s visit to Emma E. Booker Elementary School for the Sarasota Herald-Tribune. I had only been at the paper for a month or so. I was really nervous because I hadn’t covered a lot of politics and had never been in the press pool before. I was definitely out of my community journalism comfort zone. I couldn't sleep the night before and got to the school before 6 a.m. When the national press core finally joined us, there was this energy in the room that felt really tense. I misinterpreted it as big egos and kept my distance from the other photographers. I had no idea that the first plane had crashed into the World Trade Center but the tight pool learned about it while they were in the motorcade on their way to the event. When Chief of Staff Andy Card whispered in President Bush’s ear that a second plane hit, I was changing my compact flash card. I heard a bunch of shutter bursts and looked up. I was relieved to see that I didn't miss a great shot of a young student interacting with the President. Only after President Bush rushed out of the room did I learn what had happened. Without knowing it, I completely bungled an opportunity to document a defining moment in U.S. history. It felt personal because I was there in the beginning. When I ask young soldiers why they joined the military, they almost always say 9/11. I hate to be such a cliché, but looking back, I have to agree. It all started with 9/11.

In February 2003, I interviewed at the San Antonio Express-News. That day, there was a flurry of activity in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq. The paper was making preparations to send two writer/photographer teams. When I walked into Director of Photography Doug Sehres' office, he was on the phone talking about satellite devices. I remember him saying, “Fifteen thousand dollars? Ok, buy two.” Coming from a much smaller paper, I was in awe and intimidated. I had never seen so much organization and planning. But it felt a bit too newsy for me, I always saw myself as a documentary photographer who specialized in small intimate stories. I never wanted to be on the big stories surrounded by a gaggle of national media and I certainly never imagined being a war photographer.

My first week at the paper Coalition Forces bombed Baghdad.

During the next 2 years, the war always felt close. San Antonio is a huge military town. I covered too many funerals and injured soldiers. It began to weigh on me that I was seeing the end of their story as soldiers without ever knowing them as individuals. I felt strongly that if we were putting a generation of soldiers in harm's way then we owed them the courtesy of telling their stories.

So despite the fact that I could never see myself as a conflict photographer, I didn’t think twice when my photo editor asked if I wanted to spend a few months in Iraq with reporter Jesse Bogan following the Texas National Guard. So, I went to Iraq to get to know these soldiers before they came back home because even those who survived had their lives forever changed.

Nine months later, I returned to Iraq with reporter Sig Christenson to cover the military hospital in Balad. Without that first trip to Iraq, I would have never been prepared to tell the more personal story of injured soldier Daniel Barnes. I had to learn to understand and operate in a military environment. The embed system is set up to control information. So from the get-go you only get to see what the military wants you to see. There’s a reason we aren’t seeing many iconic photos like we did in past wars. It’s very difficult to find any real moments. I needed that first embed to adjust my expectations or I would have been too overcome by frustration to attempt to follow a single narrative.

TID:

What other struggles did you have initially and how did the story evolve?

NICOLE:

From the initial concept to the days before we went to press, the story evolved (or fell apart and was put back together) a number of times. Sig and I hatched what seemed like a simple plan to spend as much time as we could at the hospital and find a soldier to follow through the surgery and stateside recovery process. We asked for a two week embed and were given four days. I had imagined documenting the entire military medicine process through a single narrative and wondered why no photographer had done so before us. Rick Loomis had shot a fantastic story on the staff at the tent hospital. But I had not seen a photographer follow one soldier all the way from Iraq to Germany to the United States.

Once we arrived it dawned on us that nothing with the military is ever simple. The bureaucracy made it impossible to do the story as we originally envisioned it. For four days I slept on a couch between the operating room and the emergency room because I was petrified that I’d miss something.

When they wheeled injured soldiers in, I had to literally shove the photo release under their face for them to sign before the pain medication kicked in. There they are bleeding, and I had to say in one breath, "Hi, I'm Nicole. I'm a photographer from the San-Antonio Express-News. We're doing a story on the hospital. I'd like to take your picture. Can I take your picture?" Most people came in already unconscious, so they were off-limits in terms of identifiable pictures. Fortunately, Daniel came in conscious.

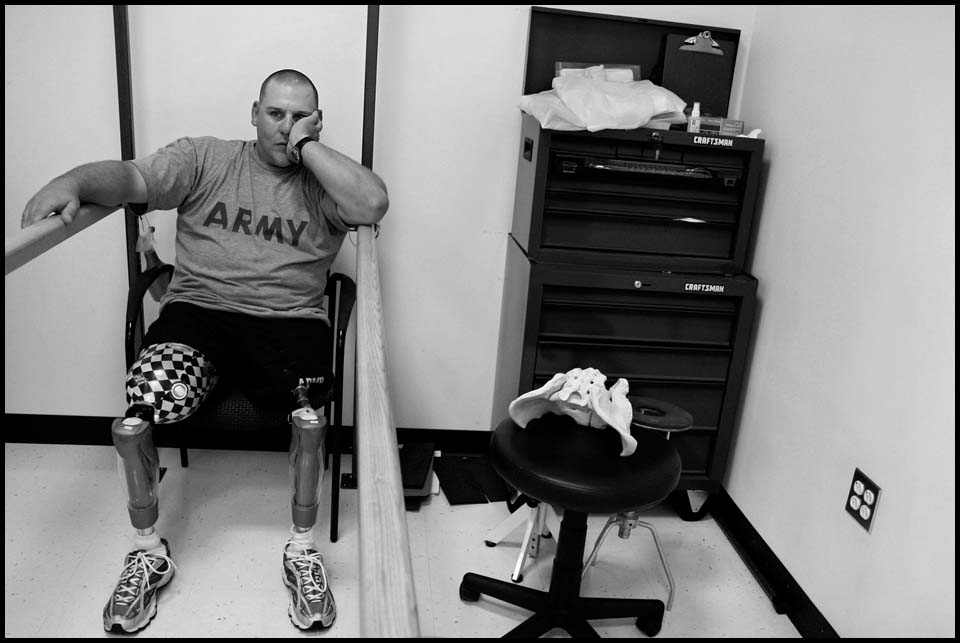

Staff Sgt. Daniel Barnes was wheeled into triage at 5:25 a.m. Daniel was on a night road clearance mission near Baghdad when a rocket-propelled grenade struck his vehicle. A few hours later, doctors amputated both of his legs in Baghdad. He was awake and alert when he came into the hospital in Balad. I was amazed that despite his injuries, he was so composed and possessed a droll sense of humor that completely disarmed the war-hardened hospital staff. We were pretty sure we’d found the right soldier to follow.

Unfortunately, Sig and I weren’t able to fly with Daniel to Germany. We didn’t have travel orders until two days later. When we did make it to Germany, Daniel was already back in the States. But we were happy to learn that Daniel was taken to Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC) in San Antonio for his rehabilitation. He could have easily be sent to Walter Reed in Washington, D.C., so we were relieved to know that he would be recovering in our own backyard. The only other soldier with significant injuries who gave us permission to document him was taken to Walter Reed. All of a sudden, all our eggs were in Daniel's basket.

TID:

What struggles did you have covering Daniel's story back home? Any conflicts and if so, how did you handle them?

NICOLE:

Even after we got back to the U.S., they made Daniel sign a release form every time I photographed him at BAMC or the Center for the Intrepid. Besides the annoyance, the formality made it feel like we were starting over with every shoot. It was like the Army kept telling him, “Are you really sure you want to do this?” Also, I wasn’t allowed to be there when Daniel took his first steps on his prosthetics. The Express-News had glowingly covered the great work that the medical staff at BAMC was doing but that didn’t seem to help with access.

That’s the funny thing about this story. Nothing ever went perfectly or as I envisioned it. But that’s documentary photography in a nutshell. It’s real life. There’s so much that’s out of our control and what’s important is to accept the imperfections and keep working, keep trying to make the best out of the opportunities you have and not dwell on what you missed.

Daniel’s and his wife Gretchen’s past experience with “the media” was a huge hurdle to overcome. Daniel’s best friend Gavin was killed in Iraq about a month before Daniel was injured. A photographer from a wire service was there and took photos that haunted Gavin’s wife and Daniel’s family. That experience, still fresh, really colored Gretchen’s first impressions of me. On our first meeting outside of Daniel’s hospital room in San Antonio, she confronted me about her reservations. I tried my best to assure her that I wasn’t there to exploit what happen in Iraq. I was there for the long haul to follow Daniel and their family as he recovered. I wanted her to know that I wasn’t interested in graphic images of Daniel’s injuries. And no single photo could define his experience.

At one point, Sig and I even took Daniel and Gretchen to lunch to try to get them more involved in the story. I showed them pictures and gave them CD full of photos and that seemed help better illustrate the kind of in-depth story we were trying to do.

This was one of the first stories where I really liked and admired the person I was documenting but I could tell the feeling wasn’t particularly mutual. I was pretty used to working hard-to-establish intimacy and once I did, it was usually smooth sailing. But Daniel, understandably, had a lot more on his plate than I did. I wasn’t a priority for him, even though he was for me. I don’t think he had the emotional space to connect in the way I had hoped. It was really confusing because he was so great to be around—wickedly funny, compassionate - and a great father.

TID:

Talk about the situation leading up to this image. What was going on in your mind as you were shooting?

NICOLE:

I set up a day to just hang out after school with Daniel, Gretchen, and their two young sons. It was the first really long chunk of time I’d had with him since Iraq. Normally, I try to spend no longer than four hours at a time with subjects because I get pretty unfocused after that point and it tends to wear people out. But this time I decided to stay as long as I could; I didn’t want to squander any opportunity and wanted to build on the momentum from our lunch. It was getting pretty late and we were all tired. Gretchen had finished doing chores and cleaning up after dinner and was about to watch Grey’s Anatomy. Daniel crashed on the couch and his sons started cuddling with him. I couldn’t believe it when his 2 year-old Jacob climbed on top of him. It felt like a veil had finally been lifted and I got a real glimpse of Daniel’s life. I had been so focused on feeling connected to Daniel, or rather, how much I wanted Daniel to feel connected to me. But witnessing the closeness Daniel had with his child was the real breakthrough moment in the story. It was a simple every day moment for them but it said everything about who Daniel was as a man and father. I just tried to capture that feeling in the photo.

TID:

You and I have talked extensively about this story in terms of working with a subject who has reservations in participating all together. Will you share your experience with that? How do you gauge when to push and when to back off?

NICOLE:

Seeing the trauma Daniel went through in Iraq and watching him go through surgery was incredibly emotional for me. I felt this tremendous bond with him. But he was unconscious for most of our time together in Iraq and never developed the same connection.

Back in the States, I just tried to find other ways to connect with him. He loved sports so I went to all the adaptive sports events that he played in. I studied up on NASCAR and begged an AP photographer friend to try and get a photo of Daniel and Tony Stewart autographed. I wanted to be able to do something for Daniel rather than just asking for his time. Some stories have a turning point, and some don't. In my past experiences, there is always some moment where I feel the barriers break down. It’s when you’ve won someone over and gained their trust. With Daniel we’d have these mini-breakthroughs but mostly it was like starting from ground zero every time.

I made a lot of unreturned phone calls. I remember staring at my ugly yellow Nextel cell phone hoping it would ring. I felt bad hounding him but I was also panicked that I was missing huge parts of the story as he slowly began to recover. Sometimes I'd ask Sig to call so I wasn’t always the bad guy. Also, I became so paranoid and was convinced he was avoiding my calls. Maybe he’d answer a less familiar number? Sometimes it worked but sometimes we wouldn’t hear from him for weeks.

He would fall off the radar but Daniel never said that he didn’t want to do the story. Every time I asked him, he would say he still wanted to do it. I think Daniel and Gretchen genuinely wanted people to understand what they were going through. They just didn’t appreciate the time it took to do the story properly. I know Daniel gave as much as he could give to the story. It’s like he was saying I want to open up my life to you but I don't want to open it up too much. I just needed to get over it, get over myself. It’s easy to lose perspective in these situations. All you can think about is the story that’s slipping through your fingertips. I didn't have the full access to tell the heartbreaking and beautifully inspiring story that was there. I could only tell a little piece of it.

I eventually had to separate the personal relationship, or lack of, from the work. So when I made the photo of Daniel and Jacob on the couch, I knew I was at least over a photographic hump if not a personal one. And Daniel was able to let go enough in that moment to give me an unguarded glimpse into his life. This is a man who was happy to be alive, that he still had his hands and arms, so he could still hug his kids. I finally felt like I was seeing that guy -- someone who genuinely felt those words.

TID:

Then the story evolved again. Talk about that.

NICOLE:

Daniel and his family packed up a moving truck and headed to their dream house in Missouri. I thought the story was over. I photographed their last days in Texas and started working on a multimedia piece with photo editor Anita Baca. I was pretty burnt out. I was dwelling on the fact that things didn’t turn out as I planned. I had it in my mind that if someone was injured, and then we had to see them walk again. I couldn’t let go and was depressed that my narrative arc had fallen through.

So when Sig wanted to travel to Missouri on deadline, I was less than enthusiastic. We didn’t even have Daniel’s new address when we booked the flight -- or when we arrived in town for that matter. I was mortified at the idea. I felt like I was stalking an injured veteran. Luckily, Doug and Anita insisted. They understood even better than I did that, at its core, Daniel’s story was a coming home story more than an Iraq story. I had to go home with him. Usually, I’m begging for more time but this time I really needed the push to keep going. And I’m so glad I did because those few days with Daniel and his family in a place they loved showed me the guy that I had seen a glimpse of watching television with Jacob. In the end, I used four photos from that trip in a twelve picture edit.

One unintended consequence of all the fits and starts was the benefit of the passage of time. Letting time pass is a key factor in many narrative stories. In this case, I was forced to do it. It was a real advantage in the end because Daniel’s recovery was a very slow process (because his injuries were above the knee). There was little progress from day to day. But a lot happened over a year and a half.

TID:

What was your emotional experience like as a person watching Daniel's struggles? As a journalist?

NICOLE:

At the hospital in Balad, I was so focused on the work that I’m not sure I processed much. I kept a blog for the paper that was as close to regular journaling as I’ve ever come. But I didn’t write about the hospital -- I was just too busy. Unlike other trips, there wasn’t enough time to decompress and make sense of what I experienced while I was there. The camera doesn’t protect you, but it sure does distract you.

I’m not sure how, but in retrospect, I have these two opposing views on the experience that somehow coexist. On one hand, it was one of the worst things I’ve ever seen. Seeing Daniel’s mangled legs lose almost all form, like lose hamburger meat, after the surgeons unwrapped the bandages on his legs, is an image I can never un-see. But on the other hand, watching the skill the doctors exhibited minimized the horror. I was completely awestruck. It really was controlled chaos and nothing like the arbitrary violence on a battlefield. I watched Daniel come back to life and that’s a pretty profound experience. The doctor told Sig that, “he was basically on the razor’s edge between living and dying. He could have gone either way.”

Seeing the trauma he went through, in some ways, I wrapped all this feeling and emotion about the war into this one person. He became a symbol of everything I wanted to say about the war, which is a completely unfair burden to place on anyone.

As time passes, I have to remind myself that the image of an amputated leg tossed into a trash can that I can’t seem to get out of my mind wasn’t Daniel’s. It belonged to another soldier. I guess, all this stuff floating around my head just got stuck on Daniel and that moment in time that I didn’t know how to process. I just had to realize the only way to do Daniel’s story justice was to approach it like I had all my previous documentary projects. This wasn’t an epic. It was a small, intimate story of one family’s experience.

Coincidentally, when we were both stateside, Daniel was trying to piece together what happened to make sense of his experience too, but he was at an even bigger disadvantage. He blacked out shortly after he was injured and his memory was really spotty. Because he really wanted to understand what happened, he pushed me really hard to see all the gory pictures that I took during his surgery. These were images that haunted me, that I desperately wanted to forget, that we would never publish, but he needed to see them to move on. At first I tried to put him off, I was worried that they would be too much to bear. I tried to read Gretchen's face to see if she thought it was a good idea. I didn’t want to upset her with the photos either. I just didn’t know what to do. In the end, I felt like he had a right to know. So in a small way witnessing his surgery did connect us, just in very different ways.

TID:

What surprised you in terms of gaining access and photographing intimate moments with this story?

NICOLE:

My first instinct was to be there for these crucial high-impact moments like surgeries, rehab, getting prosthetics, and walking. When I realized I wasn’t going to have access to all these moment-driven situations I had to change my approach. I just went whenever I could and looked for more evocative photos. I had to think about the subtleties of gestures and photos that conveyed a feeling or mood. It surprised me that I had been in a war zone, but the best photo came out of two people watching TV together. It could have easily been a mundane photo but it wasn’t. That changed the way I thought. It challenged the notion that we have to be there when something really important is happening. All the stuff I thought was going be crucial just didn't have the same resonance.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself?

NICOLE:

Again, I came away with two conflicting feelings. One, I learned that I’m tough enough to watch and deal with seeing some really horrible things. I never knew for sure how I would react and now I feel like I passed that test. But I’m a lot softer since my Iraq experiences. My feelings are much more on the surface than they use to be. I cry more easily. I let myself feel emotions more deeply than ever before. Although it can be really embarrassing to tear up at a dinner party or over cocktails, I’m really thankful that I’m much more in touch with my feelings.

I’ve also tried to keep things in better perspective. I’ve learned over time that I need to give a lot of myself when I do these long-term stories. This story taught me that not every subject would need or want that from me. It is still something that I have to do to believe in and commit to my work. But I now know it’s not a rejection of me if it’s not entirely reciprocal. I never fully won Daniel’s family over. I think the key was for me to get comfortable with that fact. It was okay that I was there to do a story and I had a job to do. It’s not that they didn't like me, it was just the dynamic of that story. But the story can still be meaningful.

On a lighter note, I also have an insane ability to be patient while dealing with bureaucracy - a great asset in my current job, photo editing for Education Week where I engage with public school officials on a daily basis.

TID:

What advice do you have for other photographers wanting to do this kind of work?

NICOLE:

We ask a lot of people. We say come open your door and share the most intimate parts of your life. It’s amazing that people give us 5 minutes. To ask people to give years, that's huge. So if they give you any time at all, take it; don't turn your nose up and say they didn't give everything. Do them justice and treat them with dignity. There aren’t that many perfect stories out there. Something is always going to go wrong. Just do the best with the hand you are dealt. Don’t give up. Be tenacious. It will be so much better than not trying and waiting for something better to come along.

Try to think smaller. The world is this huge patchwork quilt, but focus on making just one square, your story, the best, most beautiful square it can be.

Also get over your shyness, competiveness or whatever inhibits you and always talk fellow photographers at big events. It will make you feel better and more comfortable during these really unnatural situations. And they can tell you things you need to know, like a plane just hit the World Trade Center.

Finally, please, please, please don’t go into a conflict zone without insurance and hostile environment training.

:::BIO:::

You can view her website here:

TID NOTE:

This week's interview was by TID staffer and Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Preston Gannaway.

You can see Preston's work at her website: