Spotlight on Mark Mulligan

Jan 15, 2018

TID:

Hi Mark, this is a really tough image, but also very touching. Can you tell us some of the backstory?

MARK:

Thanks, Ross. I’ve always loved reading TID and I’m honored to participate.

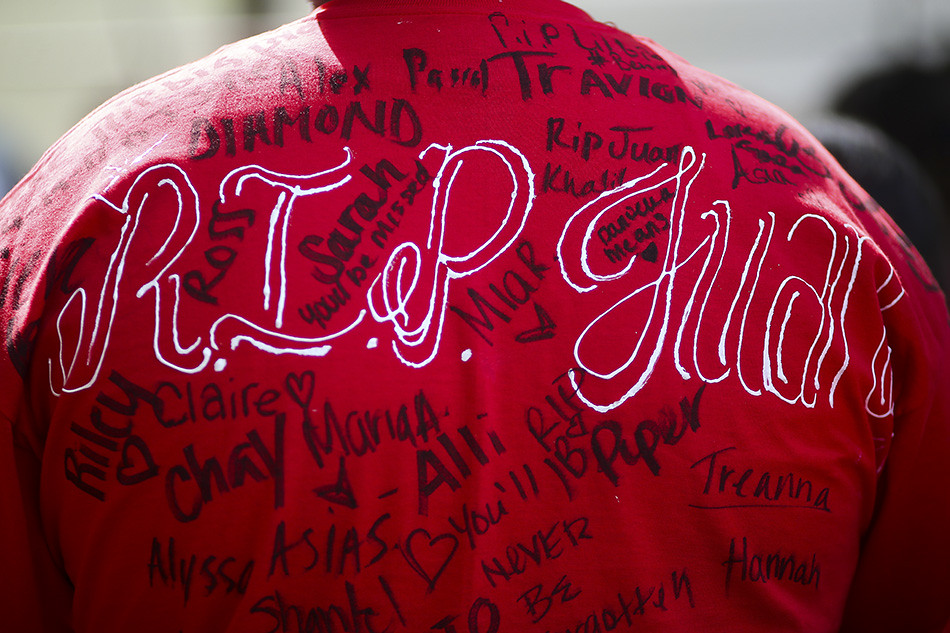

The paper sent me to Freeport the day after a 13-year-old boy named Juan Borja was killed. Word was that Juan had been shot by a friend while they were playing a Russian roulette type of game. Freeport is a small city an hour south from Houston on the Gulf Coast. The only thing the Houston Chronicle planned on covering was a press conference. Houston media, mostly TV, began to show up at the police station. After a short press conference, we heard there was a small memorial to Juan growing at the local park where Juan was shot.

The memorial seemed pretty subdued at first. Mostly kids and other community members but no family members. TV cameramen lost interest and moved to the side of the park to set up live shots. Very suddenly members of Juan's immediate family began to arrive and the atmosphere intensified. There was one other photographer there from a local paper and maybe one TV photojournalist who realized what was happening.

TID:

When things got intense, what do you mean by this and how did you react?

MARK:

By intense, I mean: genuine emotion. Suddenly it wasn’t abstract. It wasn’t a community gathered to memorialize a loss. It was a mother, siblings, cousins, grandparents - an entire extended family very publicly grieving and mourning the loss of their child.

TID:

I’m curious how you mentally prepare for something like this, and how does that help you respond when things get intense?

MARK:

I don’t know exactly. I definitely approach these situations differently now than I did ten or twelve years ago when I was starting out. Having children of my own now colors how I feel in the moment. Now I have to take a moment to push down my own emotions and not let them overwhelm me. It wasn’t always like that for me.

It’s also just repetition, and sadly by this point in my life, I feel like I’ve had a decent amount of it. A lot of daily newspaper photographers have. That said, I’d say that on our staff, I see a lot less of it than many of the other photographers. Although I do remember thinking at the time that I had just been at a memorial for a little girl who was senselessly shot in her car. It’s pretty shocking when you start to tally just how many fatal shootings are happening in and around the city.

While each situation is heartbreaking and uncomfortable, I strongly believe moments like this are important for the public to continue to see. People have to make that connection that takes the abstract to the concrete. Photography is critical in encouraging that transformation.

TID:

I think photography is about problem solving. What problems did you face throughout the assignment, and how have you worked to overcome them?

MARK:

It’s easy to start shoe-gazing sometimes at a memorial like this when nothing is really happening at first. It’s important to keep your mind working and continuing to think critically about the scene you’re seeing.

TID:

I’m also always curious about body language (as well as verbal). How did you carry yourself, and how did it influence your work that day?

MARK:

I try to make eye-contact with people. I don’t want to be sneaky. I don’t want someone to be surprised. I usually try and make a little eye contact with someone, even just a glance, to get a sense of how comfortable they are with me there as a witness. People never fail to surprise me at how gracious they can be, how they intrinsically understand what a moment can mean, how willing they are to let themselves be photographed.

I shoot with a long lens a lot, especially in situations like this where I have the ability to step back and make a tight, compressed frame. Sometimes you find yourself at vigil/memorial type situations where you are very packed in or have wedged yourself in a tight spot and have to use a wide lens right in someone’s space, which lends a different type of intimacy. For me though, if I can, I like to step back and shoot with a long lens and really tighten everything up. It gives you the full impact of the closeness of their faces and their physical proximity to each other crowded around that desk.

To follow that up, I try my best to approach people very directly to get names and talk to them when the moment is over. I want them to be clear with who I am and why I am there. I also want to get it right.

TID:

Where there aspects of covering the project that surprised/troubled you?

MARK:

It honestly shouldn’t anymore, but just the grace and strength shown by people who are in the midst of terrible tragedy never fails to surprise me. People naturally persevere.

Of course I’m troubled by the fact that a thirteen-year-old could die so senselessly. A handgun is easy to come by, and put it in the hands of anyone, especially kids, and the worst can happen. My boys are three and four years old, and I struggle with how to talk to them about what to do when they see a gun.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself while covering events like this?

MARK:

I’m a local news photographer. I don’t travel the country chasing news. But just in working for local newspapers since 2006, I’ve been to too many mass shootings. I went to Virginia Tech the day of the massacre in 2007. I was at Marysville-Pilchuck High School in Washington State after a 15-year-old killed four of his best friends and then himself at their lunch table. I was sent to Dallas the night of the police shooting there in 2016. This past November I was sent to Sutherland Springs that Sunday. Then there are the numerous local shootings that barely make a blip on the news radar.

I wouldn’t want to do this kind of work every day. I don’t know how people do. Even by this last shooting at Sutherland Springs, I felt myself feeling pretty calm and empty. It wasn’t that it wasn’t sad or emotional. I didn’t lack empathy or compassion. It just seemed normal. Eerily normal. I felt like I knew exactly what was going to happen and what it would all look like, and I realized that was a really sad state of affairs. Shouldn’t my heart be beating fast? Shouldn’t I be nervous about what was about to happen? I should have, but I wasn’t. I was worrying about how slow my wifi connection was and how that complicated getting pictures out. It just made me sad that a shooting like that didn’t surprise me any more.

TID:

What have you learned about others?

MARK:

Anyone who is reading this believes photos are important. They allow the viewer to be somewhere and experience something they may never have gotten the chance to live themselves. The same is true with photos of grief. Photography prevents people from ignoring the reality of an event. You have to look it in the face. You have to confront it.

My interest in photography came from consuming great photojournalism and feeling all of this horror and compassion and empathy and amazement of what I was seeing in front of me. I realized that my goal was to take pictures that made others feel the way I was feeling when I looked at great documentary photojournalism. It’s an important job that we can’t shy away from.

After the Sutherland Springs shooting, there were a lot of articles by members of the media criticizing the media for the crush they were causing in that tiny town. It was overrun, lawns were being trampled and locals were afraid to come out of their homes while cynical members of the media sneered and joked and preened.

Well, that’s true to an extent - Sutherland Springs is tiny, and there were A LOT of media there, but I would argue that a lot of great journalism was being done. Harrowing stories were told, light was shed on a confusing situation, questions were asked, facts were clarified - real value was brought to readers and viewers all over the world from the site of a horrifying tragedy. It couldn’t be ignored.

That gets to the root of where some of that criticism within the media comes from - discomfort. I think its easy to confuse your own discomfort in a situation for moral ambiguity. The fact is, our job is often uncomfortable, but we have a responsibility to be there as a witness, and as long as your own ethical values are properly lined up in your own head, you’re going to be comfortable with what you’re doing and how you’re doing it.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Can you talk about the main image, and the moments leading up to it?

MARK:

Like many moments, it just sort of all lined up in front of me. I had very little to do with it aside from moving my feet and pressing the shutter.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers who cover this type of work?

MARK:

It’s important to know what your motivations are when you’re taking pictures. Are you serving your community? Are you trying to reflect reality? Are you trying to generate compassion? Or are you just trying to “get a shot”? You’ve got to get those questions answered for yourself.

:::BIO:::

Mark Mulligan is a staff photographer for the Houston Chronicle where he takes pictures and flies the Chronicle’s drone. He is married to photographer Annie Mulligan and dad to two hilarious boys. Mark went to the University of Texas at Austin where he started working at the college newspaper. He moved on to working for weekly newspapers in Virginia, and then worked for seven years at The Daily Herald in Everett, Wash. A native Houstonian, Mark moved home to Texas with his family in 2015 to work at the Chronicle.