Spotlight on Marcin Szczepanski

Oct 10, 2013

TID:

What a beautiful image. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

MARCIN:

First, thanks so much for presenting my work on The Image, Deconstructed. I’m a big fan of your blog and I’m very excited to be part of it.

The image comes from the project People of the River that I’m working on in Brazil. The photo was shot in Pantanal, one of the largest wetlands in the world. It captures a fairly rare moment of the residents of this remote fishing community frolicking in the water. The river is full of piranhas and caimans so it’s quite dangerous to wade into it. In fact, piranhas ate a toddler that fell into the river not far from that spot a couple years earlier. The image captures a spontaneous and carefree moment but in this case, it’s important to know the backstory.

TID:

This is part of a larger body of work, can you tell us about the project?

MARCIN:

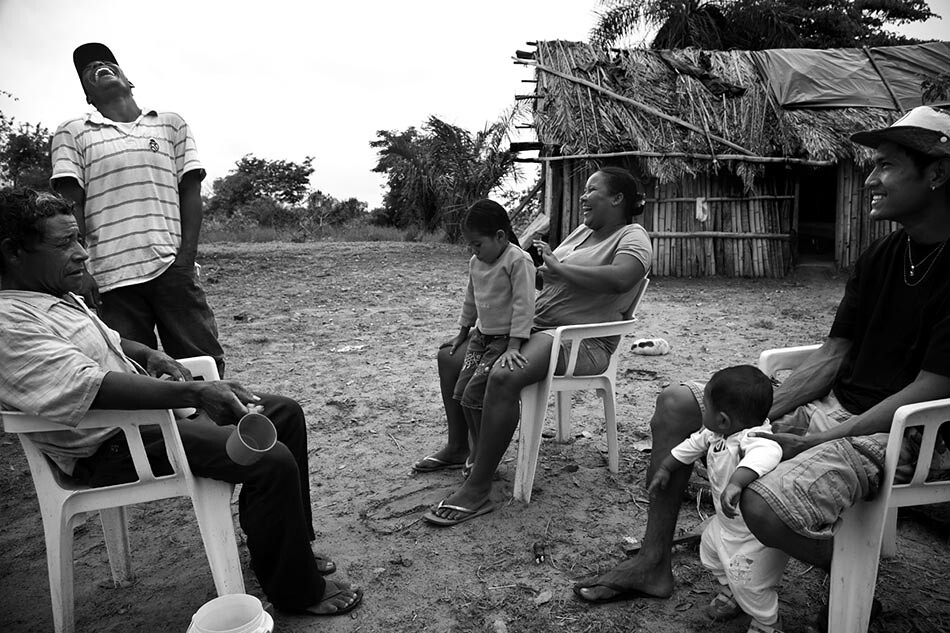

I’ve been shooting the project People of the River in the southwestern part of Brazil called Pantanal. Pantanal is one of the largest wetlands in the world. It’s mostly known for its amazing animals like jaguars, hyacinth macaws, caimans (jacares), yellow anacondas or capybaras. The Pantanal ecosystem rivals the Amazon and is thought to be home to 1000 bird species, 400 fish species, 300 mammalian species, 480 reptile species, etc. The flora and fauna are well documented there. Much less is known about the people living in Pantanal today, especially so-called ribeirinhos – river people, people living on the banks of the rivers that crisscross the swamps. My project aims to fill that gap. It documents humans living in this incredibly beautiful but also very dangerous area. Jaguars are spotted around the village almost every night. The first night I was there a jaguar attacked and wounded a horse. A week later another jaguar chased after a dog and ran into a house of one of the families. The family survived and was able to escape but they had to move out of the house for a couple days. There are all kinds of snakes, insects, and animals that can kill you there. 80% of Pantanal is submerged under the water for a big part of the year and it takes 30 hours by a motorboat to get to any kind of civilization for a lot of the residents. Most of the people living there are of Indian descent; the ones I focused on are fishermen. I’m working to document their day-to-day life. The overarching theme for the project is the idea of survival in these pretty harsh conditions. Ultimately the project will have several chapters; one of them will focus on family relationships, another on the nature of the relationship between residents and animals that surround them, both wild and domesticated. I call my work in Pantanal an ethnography, in the sense that I hope to explore and document the changing culture of Pantanairos, people living in Pantanal.

I’ve been to Brazil and Pantanal a couple times before but I started working on this project last summer. I guess the key here is that I wanted to approach the ribeirinhos (river people) community and the project without any preconceived notions of what my “angle” should be. I had no agenda beyond the documentation. The initial part of the project was self-paid so I didn’t owe anything to anyone other than myself. I tried to keep my eyes, heart and mind open. I started the project in June 2013 by spending two weeks living in a tiny and remote fishing community in the middle of Pantanal. The community is separated by 250 km of marshes and water from the nearest town. I photographed the life the way it unfolded around me there. I wanted to move past the exotic and focus on people as real human beings, people we can relate to. It takes time to reach a certain level of intimacy and I plan to go back to the community and spend more time in the area, nurturing the friendships that I was offered there. I don’t think I’ve reached the level of intimacy in my images that I’d like to, yet. But it’s a good start.

TID:

What was your motivation in working on this project?

MARCIN:

There are a couple layers of motivation for this project.

First, I’m fascinated by rivers and people who are sustained by rivers. There’s something magical about the water to me as the ultimate source of life. From a more rational perspective, when you look at the history of human kind, you notice that people have always settled by the rivers. Mesopotamia is often called the cradle of Western civilization. It developed along Tigris-Euphrates river system. Most of our large cities were established by large rivers that could sustain civilization and development. Unfortunately, you can also notice how humans and urban architecture have often turned their backs to the rivers in the last 50 years. I wanted to explore the relationship of people to water, to a river and marshes. I wanted to help bring back to the rivers some of the respect that we owe them.

Second, I wanted to immerse myself in a small community and be able to photograph it 24/7. I’m a former Detroit Free Press multimedia photojournalist. I work for the University of Michigan now. Documenting the human condition to me is the most meaningful thing I could do with my life, next to raising my two daughters and trying to be a good husband. To quote my photographic hero Eugene Richards, I try to work in the “nexus of social awareness and art”. I think it’s extremely important that people learn about other people, other cultures, that we recognize and appreciate the universal humanity of all people on the globe. It’s extremely important that we realize that people on the other side of political borders, or on the other side of social or economic divides, are just like us. They laugh, love, take care of their kids, cry when they are hurt, want to be happy. The fear of “the other” – this ignorance and arrogance – is one of the main causes of violence and cruelty in this world. I hope to do my little part to counteract that.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working on this project?

MARCIN:

The first challenge was logistics – how do you get to a tiny village (maybe 15 houses) in the tropics, in the middle of one of the largest wetlands in the world without spending a fortune. How do you find a roof over your head in this village and how do you find food to eat there? How do you charge your batteries if there’s no electricity? You can’t just show up, pitch a tent and start taking photos. For one, there are jaguars roaming around the houses almost every night, 3-meter-long anaconda and all kinds of other animals and insects that can kill you quite quickly. Two, people need to be given a say in whether they allow you to be there before you show up.

I was really lucky because I was offered help from the only NGO that works in Pantanal called ECOA. ECOA is doing some amazing work, helping give voice to the residents of Pantanal, helping them regain some of the rights to fishing and the ability to sustain themselves that they lost when a lot of the area around them was turned into private nature reserves. The establishment of nature reserves cut off the residents’ ability to fish in the area where they have lived for generations. Andre Luiz Siqueira, the director of ECOA gave me a ride in his motor boat to the village, introduced me to the residents and helped secure a place to sleep in one of the fishermen’s houses. The residents would often give me rides in their boats from one house to another, since oftentimes the houses were separated by marshes. People who had very little to eat – basically fish and rice, would always invite me to lunch if I happened to be hanging out near their house around noon. I would join my host’s family for breakfasts and dinners. Access to electricity to charge my camera and laptop batteries was a big issue. But a small public school was established in the community a couple years ago and they would usually run a gas-powered generator overnight. The teachers were very gracious to let me plug my chargers there. It used to be that you only needed some small batteries for your film camera, but now in the digital world, access to electricity is crucial.

The second challenge was cultural adjustment. I traveled extensively internationally before and I’m used to being in foreign countries. I’m a Polish immigrant in the USA, for one. But the US has been home for 13 years now and I got used to being able to make plans for the day and being able to execute my plans, being able to predict what I may be able to do during a particular day. So for the first week in the village, I would wake up at 4am (there was no electricity in the house I was staying in so I would go to sleep at 8pm), lay in the darkness and plan what I wanted to shoot that day. And then 80% of my plans would fall through and I would get frustrated, because I was not able to get to where I wanted to be, the person who was supposed to give me a ride would be 3 hours late or someone who agreed to have me accompany him fishing would change his mind. I spent way too much time being frustrated and trying to cram too much stuff into a day.

Finally, I realized that I wasn’t in control of my destiny there, that I was now part of the village system and that I needed to adjust to the way things happened there. Once I did that, I was able to relax and actually be much happier and at peace with myself. I let the river of life there take me where it wanted to take me rather than trying to desperately struggle against the current. Once that happened, I stopped making plans and I just let myself photograph whatever was happening around me wherever I happened to be. I slowed down and I was able to be more in the moment, enjoy the time and space the way the residents did.

Third challenge is pretty obvious. It was working to gain trust of the community. The community members have had some bad experiences with “photojournalists” in the past and they are understandably weary of outsiders with cameras. I made some friends in the village. Upon return to the US, I sent them prints and a point and shoot camera for one of the residents who is interested in photography. But I think most important is being able to go back, show them that you care and to reinforce the relationships over time.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

MARCIN:

I kind of combined that with the previous question, hope that’s OK.

TID:

What issues did you mentally struggle with while working, and how did you deal with them?

MARCIN:

I wanted to approach the community with open eyes, open mind and open heart. I didn’t want to make any preconceived plans of what the story I wanted to tell would be. Too often, we tend to bend the reality to match what we think the story is. I saw a very clear example of that in the village, when one day a film crew from the Brazilian ESPN showed up. They arrived in two boats, covered in camouflage up to their teeth. They came for literally 3 hours. They wanted to shoot a program about poor, Indian Brazilians from the marshes playing soccer in the water. The whole thing was ridiculous. The film crew’s director staged the whole thing. They made kids kick the ball in the middle of a flooded area, upsetting the parents who would never let their kids play there. They made the soccer players parade through the village repeatedly so they could get shots from different angles, they created some mythical team from another village that was supposed to arrive in boats for the game, told one of the residents to take off her glasses because she looked “too civilized” and not Indian enough. It was disgusting. They turned the social order of the village upside-down to achieve their narrow goals, to uphold stereotypes. People in the village are not stupid; they were upset about the whole thing. They felt powerless and used. My blood still boils when I remember that day. It’s an extreme example of what I wanted to avoid. If only the film crew took their time and learned what the reality was really like, they wouldn’t have alienated the residents and they would actually have got much more powerful shots that would show reality, not fiction.

It’s an extreme example of what I’m hoping to avoid. I didn’t want to decide what the story I would cover was before spending time in the village, observing and talking to the residents. I wanted to approach the community with an open mind, treat my notebook and camera as a tabula rasa (blank slate). It was very challenging for me because I’m a storyteller. I’m a storyteller but here I purposefully designed the project so I didn’t know what the story was. I’m trained to and usually work hard to shape reality into stories, to figure out where the struggle, conflict is, who the characters are, how to make sense out of it all. But here I had this whole village universe in front of me and only two weeks to make some sense out of it. So I struggled. I photographed everything around me, talked to residents, did some video interviews. I was trying to make sense out of this place, find some common themes, but also I didn’t want to narrow down the scope of my documentation quite yet. It wasn’t until much later, when I got back, when I had an opportunity to look at the images, process those two weeks in the village, talk to some amazing people like professor Loret Steinberg from RIT and former National Geographic Director of Photography Tom Kennedy, that I was able to start figuring out what this project is, what the scope of this ethnographic document could be and that I absolutely have to go back there to keep working there. These images are only the beginning. The future time in Pantanal and the time away from Pantanal will together shape what comes out of this project. Pantanal and its residents face some serious challenges. I plan to be able to document these challenges and the changing world or the river people.

TID:

Now, onto the main image. Can you tell us about the moments leading up to it, and what was going through your mind when you made it?

MARCIN:

The image was taken late afternoon in a tiny fishing community lost in the middle of Pantanal in Brazil. That particular day, a huge storm was gathering and just before it hit the village, a group of teenage boys and men in their 20s from the community jumped into the river to cool off and wash off all the dirt and sweat from the soccer games they just played. Almost every day teenage boys and men in their 20s participate in pick up soccer games in the village. That day was no exception. The scene is actually highly unusual since the river is full of piranhas and caimans (jacares) and people don’t just casually hang out in the water. The whole thing lasted maybe 3 minutes and the players were out of the water.

I noticed that the guys jumped into the water and I followed them. I took a couple images and then squatted to be right next to the water surface with my camera, I wanted the river to be a big part of the image and I was actually able to frame the shot with some grass blades rising above water and the people in the back. The whole action lasted seconds only and then it was over. I was lucky I moved and thought quickly. The years of photojournalistic training kicked in at that moment.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment that you weren't expecting?

MARCIN:

I was excited and surprised to capture the residents directly in the water. Men and some women spend a big part of the day in boats and canoes but they rarely jump into the river. I hope there’s also something spiritual about the image and that moment.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

MARCIN:

I learned that the sooner I can let go of trying to plan and to control the world around me in places like Pantanal, the better my images would be. I also experienced something probably very obvious, that the more time you can spend with people you document, the better your images will be. I learned to better follow my instincts and trust them more. I worked for newspapers for quite a few years in the past and I absolutely loved it. But newspapers, especially today, can constrain you in the way you see the world, there are certain expectations of your work and you as a photographer. In Brazil, I was able to listen to my own soul a bit more and to follow my instincts in what I photographed. It was a great experience.

Finally, I learned how thoroughly I enjoyed photographing the people in Pantanal and how much I absolutely loved being able to focus almost exclusively on still photography. I started out as a still photographer, photojournalist. It is my first passion and love. But I’m also a multimedia producer and I’ve spent the last several years shooting and editing video. I love the ability to give voice to my subjects that video and film offer and I’m grateful for my filmmaking skills. But it was such a pure joy to focus almost exclusively on still photography, to feel it with every part of my body that I can’t quite express it in words. The People of the River ethnography will be a multimedia project. It will have a video component but photography will continue to be the dominant element of it.

TID:

What have you learned about others in the process of making images like this?

MARCIN:

I learned that people are essentially the same no matter where you go, in terms of their desires, goals, ambitions. We are all the same. We want the best for our kids. We desire strong families and communities. We want the future generations to be better off than we are. Another thing I knew already from my previous travels, but it was re-affirmed in Pantanal is that people will take care of you and help you if you put trust in them. I trusted people there with my life. I made a couple good friends in the village. I think of them very often and I very much appreciate their friendship, generosity and kindness. I hope I will be able to reciprocate it.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

MARCIN:

When I was in Pantanal, I drank the same, mostly unfiltered river water and ate the same rice and fish every day like everybody else. I wore similar outfits to what the residents wore. I talked about my wife and kids while asking about their families. I know I stuck out like a sore thumb but in the same time, I tried to convey how much I respected the people there. I wanted to let them know that I was there to learn from them. I was grateful for everything and I tried to show it. I think humility is not a bad approach to working in a foreign country.

On a more universal note, I believe documentary photographers and journalists have a responsibility to the world and to their subjects to be truthful and honest. I think our main concern should be how to represent the reality in an honest manner. There are all these decisions we make about what the angle and focus of our story will be, how we photograph something, which moment and composition of individual moments we pick. It’s complicated because even converting color images to black and white makes a huge difference in the way we respond to the images, and how they reflect the reality. I thought a lot about how much personal interpretation of the reality I’m engaging in, how much the project is the projection of my own fascinations and interests and how much I’m documenting the reality, whose reality I really capture. I think I’m in peace now with where the project is going but it was really good to struggle and think through all these issues. I guess my advice for photographers is to engage in some kind of post-modernistic thinking of deconstructing their own images, their work, motivations, feelings, the decisions they make. The Image, Deconstructed may be a good inspiration to do just that.

:::BIO:::

Marcin Szczepanski is a senior multimedia producer at the University of Michigan. Before accepting a job at the U-M, Marcin was a staff video producer and photojournalist for the Detroit Free Press.

In addition to current communications work for the University of Michigan, Marcin uses multimedia tools such as photography, video, text and audio to document socio-economic issues of inequality, human rights, cultural identity and international development. He creates films and photography that explain the world we live in and hopefully bring people closer together. Marcin's multimedia work has appeared in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and a variety of other publications. His work has received a number of awards throughout the years, including three regional Emmy Awards (in Michigan) and a title of 2010 NPPA Photographer of the Year in Michigan. Educated as a sociologist and photographer, Marcin has traveled and worked in Brazil, China, Russia, Mongolia, Guatemala, Morocco and Europe in addition to the US. Marcin was born and raised in Poland. He moved to the United States in 2000.

You can see more of his work here:

People of the River project: