Spotlight On Maggie Steber

Feb 3, 2012

This spotlight was originally published 02/05/2012

TID:

Maggie, thank you for taking the time to talk with us. We're going to be focusing on a body of work you did on the concept of memory. Can you talk about the origin?

MAGGIE:

The story came from National Geographic. It was a science story, but because it was about the very ephemeral concept of memory, they wanted a humanistic approach. We were dealing with both the science of recall and the tragedy of memory loss. My aim was to make photographs that spoke to the subject's remembering or forgetting, as well as the scientific beauty of the brain. I also wanted to make images about the ravages of Alzheimer's. The challenge in photographing for NGM is to be surprising as well as exact, to be lyrical as well as serious – all while bringing new ideas to light.

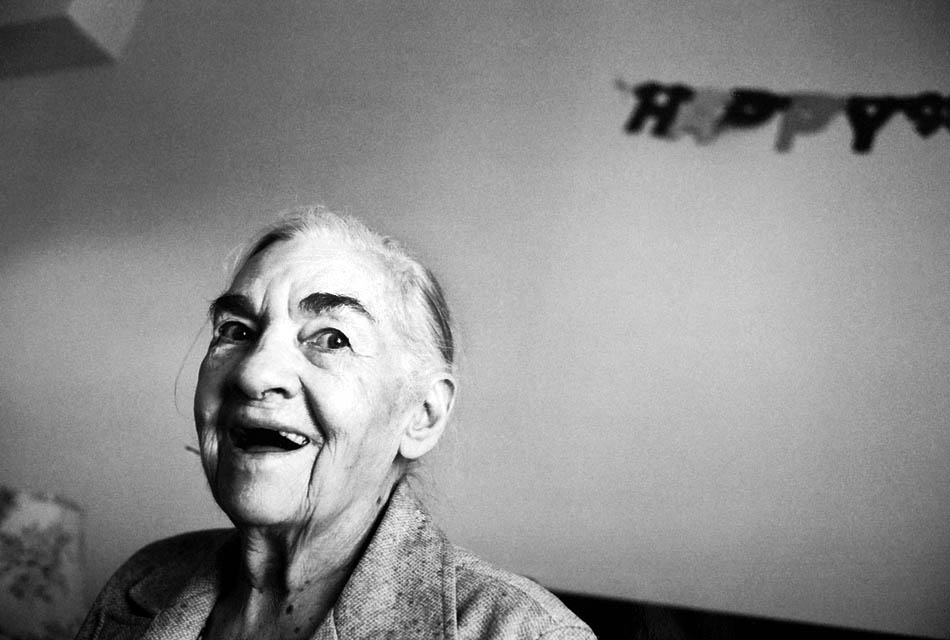

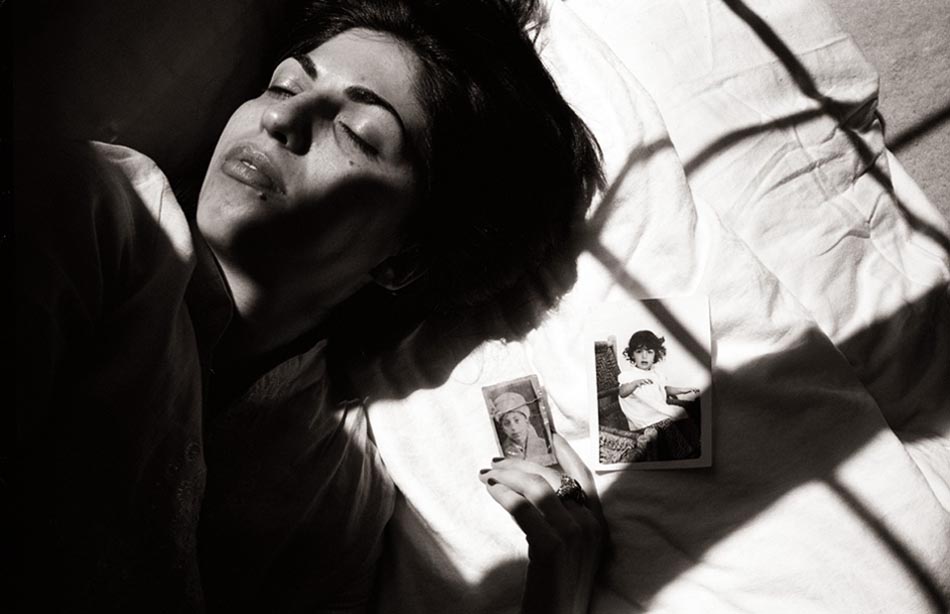

The memory story had a special place in my heart because at the time I shot it, my mother was suffering from dementia. She suffered from memory loss for about 7 or 8 years. I photographed her throughout as a way to get through it myself and to make new memories for when she died. The magazine ran a sidebar spread that I wrote about my mother at the end of the story. It was very powerful for me, and it really personalized the story in a way that readers could relate to. They weren't only learning about the stories and the science of memory, but witnessing someone who was watching her own mother disappear before her eyes.

TID:

A subject like 'memory' doesn't have any clear contours or guides for storytelling - you had to make the rules. How did you focus this body of work?

MAGGIE:

I wanted to create a certain look in the photographs. I thought about shooting the photos in sepia. I shot film on the story because of the color palette, but I thought about transposing the color to sepia since that tone evokes a sense of memory. In the end, we ran it in color. I also didn't want it to be too tragic, although there was at least one tragic story: capturing the fear and pain of losing one's memory, losing one's self.

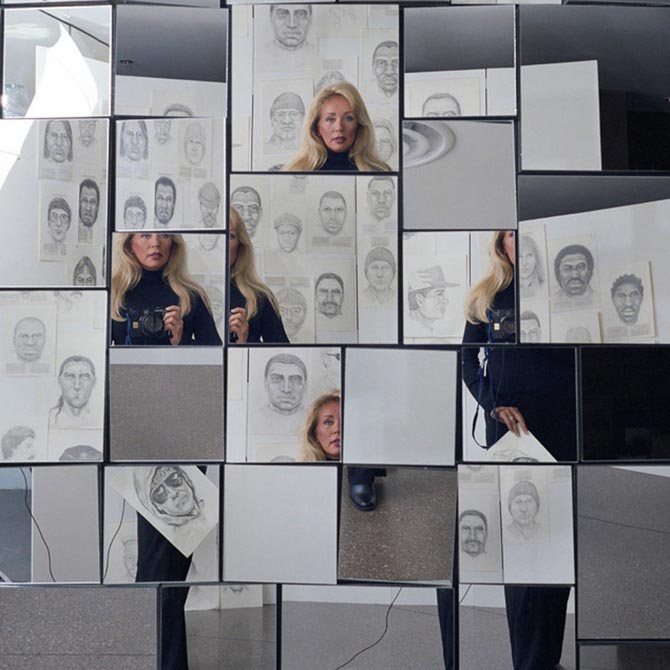

I wanted to show the brain - the memory box I called it - and I wanted the pictures to look as though I had opened your skull and photographed your memories right from your brain. I had to keep this idea in mind so the style would be consistent, even though each situation was different. I was also drawn to the mystery part of memory and how memories change every time we recall them. I researched what I needed to cover from the writer's proposal, but I also had to write a photographic proposal on how to move the story forward.

TID:

Through these images, the viewer sees an interpretation of the subject's memory. Can you explain your process for listening to someone's memory and then interpreting it? For instance, with the portrait of Elly Chovel in the water?

MAGGIE:

I met Elly Chovel at another assignment and found out she was a founder of the Pedro Pan Organization, and fled Cuba at an early age. She told me how she swam in the waters off Key Biscayne daily at dawn because the waters lapped the shores of both Miami and Cuba. When I was thinking about the memory story for NGM, I remembered Elly and thought her story would be a beautiful thing to photograph. One morning before dawn we went swimming in those waters. I photographed her as the sun rose. She was swimming in a sea of memory... It was a serene moment and really reflected the power of memory. I love listening to peoples' stories, and I think we should listen to them - they will tell us, if we are truly interested, all kinds of wonderful things about the subjects. From this, we have some hint of making a photograph that reflects their story.

When I photograph someone I always zone in on them. I'm all there and I'm looking for small signs or signals - I guess you could call them moments - they are what make a good photograph. The morning we shot this photo, Elly was just swimming so easily. Her head seemed to float on the water; she seemed almost asleep, but I knew it was because she was remembering. That's so powerful. I was steeped in the story of memory and the experience of seeing my mother's memories disappear had a profound effect on me.

I was inspired by the power of this and how, in losing memory, one can lose one's self - be it dementia or forgetting a birth country. To remind herself of Cuba, Elly swam in the sea, in her memory. I get lost in this idea in the best sense of the word.

TID:

Was there something that surprised you about this project?

MAGGIE:

I learned a lot about the science of memory loss, about some remarkable research with birds, and I found ways to show the effects of the science in more personal terms. The science and research is elegant, in a way. I met a scientist who spoke poetically of his 30-year research on bird memories. In a funny way, the story was cathartic for me. I started a sidebar project for myself called “Memory Box.” I tried to interpret various memories of my own or of other people in a visual way. I think it's good to do something more personal, because sometimes those photographs can end up in a story as narrative. I still work on this project and I really love it in the way that you love eating dark chocolate in the middle of the night.

TID:

What were some of the difficulties you encountered working on this story and how were they resolved?

MAGGIE:

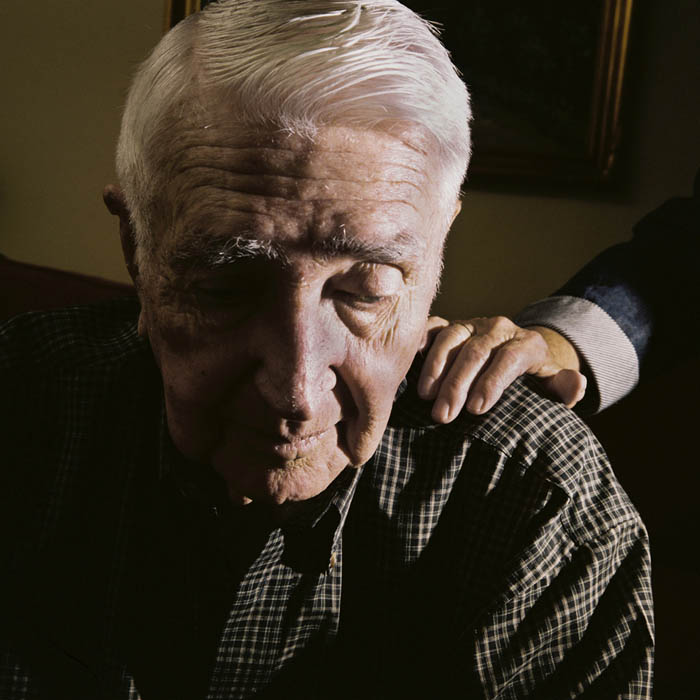

Getting permission for access to certain things was tough. I wanted to photograph a man whose memory was lost when a virus ate part of his brain. He lived at home and was the longtime subject of a scientist who was very protective. Finally the writer and I convinced the scientist to take us to the man's house where he lived with his family. We got 20 minutes with him, and I had about 5 to do a portrait. I used light and shadow to explain that half the man's mind was in the light and half of it was gone and in the dark. It was an important aspect and the photo was the second one in the story.

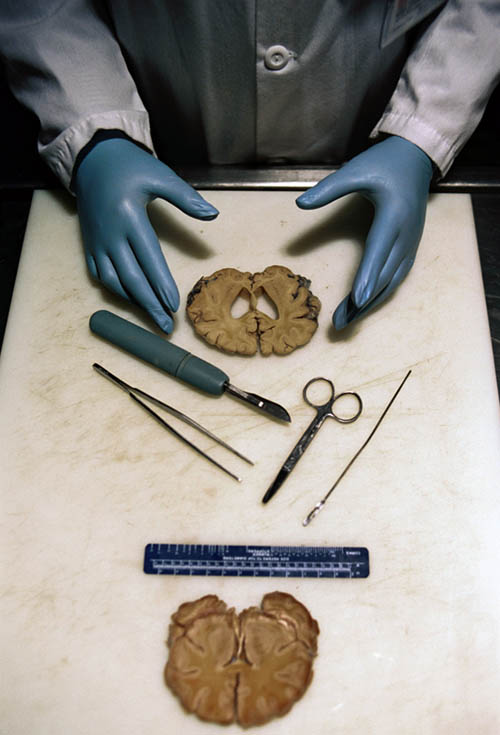

But the best story was this: I wanted to photograph slices of brains, a normal one and one ravaged by Alzheimer's. After asking dozens of brain banks around the U.S., one finally agreed at UCLA. In a lab used for autopsies I spent the day with 2 one-inch thick slices of brains, one normal and one showing the effects of Alzheimer's. Photographing those slices all day, every which way, on various levels of plexiglass, I became very familiar with them. It was hard to let them go at the end of the day. I had worked all day with the repository, pickled as it was, of someone's memory. Looking at the brain you wouldn't imagine anything would happen there; it's so massive.

TID:

Which came first: your project on your mother, or this assignment?

MAGGIE:

I started to photograph my mother before I got this assignment, and I think I got the assignment because of the work I had been doing. Watching my mother go through memory loss was very tough. My family was my mother and myself, and watching her struggle with losing the very core of her being was a bit like watching our life together go. There was so much to do: I had to keep her from being over medicated, I had to find the right caregivers and everything from taking care of her long distance, to finally moving her. Researching medications, the financial cost and spending time with her was challenging for me, on top of the knowledge that she was coming to the end of her life as we both knew it. This was why I began to photograph her. She never let me take pictures of her before, but now she didn't even pay attention. The photographs enabled me to deal with the huge job before me and also to make new memories. It got me through it.

And of course, the experience gave me a glossary of information and ideas about the science, the medical and social aspects and the high emotional toll on all parties. It informed and largely shaped aspects of the coverage. When I met others with memory loss - whether it was a man who had lost part of his brain to a virus or people living in facilities - my understanding of the challenges, the huge emotional toll on the families and the individuals, was personal. I tried to interpret their stories in an empathetic way, like traveling with them down a path that I was also on. I understood all the moving parts in this mosaic of loss. I also tried to approach the ideas of science with a humanistic approach, particularly because my mother had been a scientist.

TID:

What was the reaction after this story was published?

MAGGIE:

The editors liked it very much. It was bookended, so to speak, by two very personal homages: an editorial by Chris Johns, the editor, whose father had suffered from dementia before passing away, then by the sidebar on my mother, where we used an essay and a couple of photographs. I think people responded to the piece because many readers were seeing the same process happening to their parents, or they knew someone who had suffered memoir loss. It felt like a very intimate experience.

TID:

What advice do you have for others who want to approach this type of storytelling?

MAGGIE:

I cannot stress this enough: do your research! Don't repeat what has been already been done. Many stories have been done about memory loss. It's hard to avoid repeating some aspects, but there are also lots of new ideas and new things to show. A story or project like this is not just about the science, it's also emotional. And beyond emotional, it's also about the social and financial impact on families and our economy. It's important to look at all aspects of a story, which really takes a lot of research and thinking about a fresh approach. If you can't find something fresh, something new to photograph, then you aren't doing your homework. That's 50% to 75% of the work.

I kept the emotional thread as a character in my story, but it was subdued and subtle. The look on someone's face can tell the whole story, but only if you recognize it. Telling stories is not just taking nice photographs. They have to be meaningful photographs with layers of foundation beneath them. There are only a few ways to get that. The other thing I have been thinking a lot about lately is how we tell stories, how we imagine them, how we edit and sequence the photographs, and in the end, what it says, what it means. I think now, more than ever before, we have to think about these things.

I shot video of my mother and collected audio, mostly so that when she was gone I could watch and listen, which was very important because she stopped talking. I initially had no purposes for those beyond personal use, but now they are being incorporated into a larger piece I am working on with Brian Storm of Mediastorm. You never know where a project can lead you and nowadays it's a good idea to be collecting these things. I like what the late Tim Hetherington said: "We live in a post-photographic world now and we need to think in broader and fresher terms." I'm especially keen now at looking into how Europeans edit photographic stories because the have a very different point of view than us Americans. It's a bit more existential and less obvious. In many ways, it's liberated from structures that we impose on our storytelling. I love tradition, but if we are all telling stories in the same way, I think we do our subjects a disservice as well as the public.

TID:

You said earlier, "I still work on this project and I really love it in the way that you love eating dark chocolate in the middle of the night." Why did you choose this metaphor, and what do you mean by this?

MAGGIE:

Eating dark chocolate in the middle of the night is a hidden secret pleasure. No one needs to know about it. In that way, it is mine alone. It's like a secret garden, where I can retreat and work on something and it doesn't matter whether I ever show the work and if anyone likes it or not. It's where the dark side of my personality can come out to play and thrive. It's like a guilty pleasure. I've thought about this a lot.... maybe this is where one's work reveals a longing to be free of one's self. I think we are described, for the most part, by how people regard us personally and professionally. In this secret garden where I might "eat dark chocolate in the middle of the night" I get to define myself and my work. I think this is a healthy and critical thing for anyone engaged in the creative process.

TID:

Finally, what did you learn about yourself in the process of making these images?

MAGGIE:

I learned that I really love science stories to which I can bring a human element. I also discovered a fascination with the brain - a terrain that science has not managed to fully map. We have a better notion of how the universe works than how the brain does. I learned that memories are carried on neurons and when you recall a memory, a little electrical synapse occurs. The science of the brain - moreover memory - is exquisite and spellbinding.

More importantly, I thought a lot about the meaning of memory. We really are described by memories, personally and collectively. Our own memories shape us. What we remember of those passed shapes them. It is really quite a powerful thing, both in social contexts and in how each person sees themselves. Did you know that each time you recall a memory, you recall it in a different way - each time! In terms of history, that's an astounding thing to think about. Can we ever get to the truth or reality? It's a big concept. I'm still mourning my mother (maybe we never stop) and I find that the memories I have of her, little inconsequential moments, fiery moments, her singing and dancing, cooking, working, fussing at me.... I love having all these things. They are vitally important, I would even say critical. When we lose memories we are lost. I love having all the adventures I've had, because one day when I'm an old woman, I can sit in a rocking chair and remember my life... if I'm lucky enough to hold onto the memories.

***

Maggie Steber is a documentary photographer known for her humanistic stories of people and cultures in crisis. She has worked in 62 countries, and worked for over 25 years in Haiti, publishing a book with Aperture entitled DANCING ON FIRE: Photographs from Haiti. She has also produced significant bodies of work on Native Americans and memory loss.

She has worked as a contract photographer for Newsweek Magazine, a photo editor for Associated Press and the Director Of Photography/Asst. Managing Editor for Photography and Features at The Miami Herald. She has served as a judge for numerous photographic competitions, including the World Press Photo Foundation and iPOY competition. Steber has taught workshops such as the World Press Photo Joop Swart Master Class, the Foundry Workshops, and at the International Center of Photography in New York City.

Her awards and honors include:

Pulitzer Prize for News Coverage, The Elian Gonzalez Story, Miami Herald 2001; The Leica Medal of Excellence; First Prize Spot News World Press Photo Foundation News; First Prize Magazine Documentary in Pictures of the Year (iPOY); Oliver Rebbot Award Best Photographic Coverage from Abroad; The Medal of Honor for Distinguished Service to Journalism from University of Missouri; Alicia Patterson Foundation grant; Ernst Haas Grant; Knight Foundation Grant

Exhibitions/Collections Samples:

Library of Congress American Women Photographers Collection; Pingyao and Lianjhou Photo Festivals, China; Visa Pour L’Image, Perpignan; Jardins du Luxumbourg, Paris; Smithsonian Institution Exhibition/Collections; New Orleans Museum of Art (Art of Caring, traveling exhibition) and collection.

To view samples of her work go here: