Spotlight on Jerry Wolford

Jun 22, 2015

TID:

Thanks for being open to this, Jerry, can you tell us a little of the backstory to the image?

JERRY:

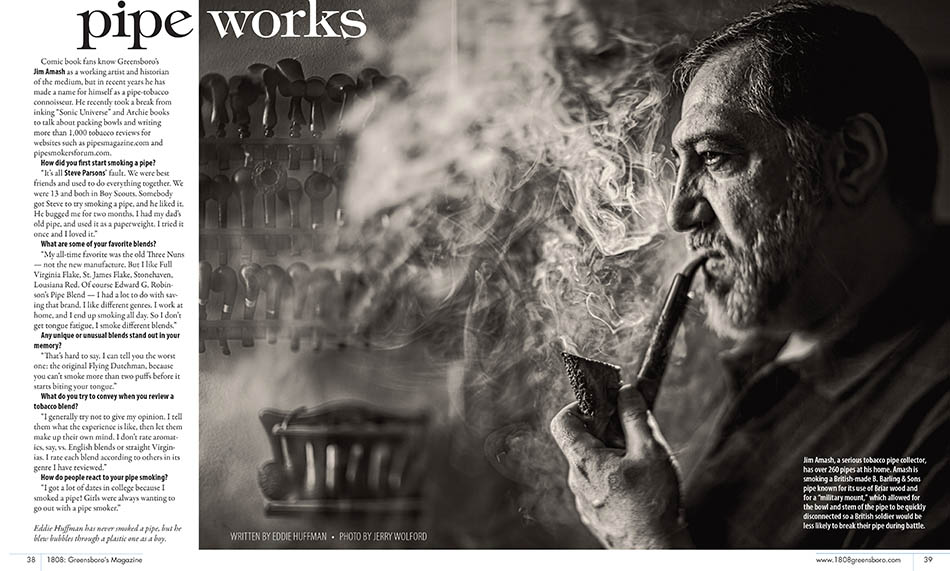

Thanks for inviting me back to such a wonderful forum of visual knowledge. I am happy to have such a gem of a photo discussed, because it is my favorite kind of image. This image seems to have forced itself onto the stage without me fully understanding how. The backstory of this shoot is how it was an assignment that almost never made it to completion. The subject, Jim Amish, an avid tobacco pipe smoker and collector, works a third shift schedule at his home as a comic book artist and we spent days just trying to set up an assignment with him. I think it was assigned to a couple staff members before it came my way. The other odd thing about the assignment is that is was for our newspaper’s new standalone magazine, 1808 Greensboro’s Magazine. We don’t usually shoot assignments for the magazine, but the photo department was helping out with staffing.

TID:

What sort of planning did you do in preparation for the shoot?

JERRY:

Well you know how newspapers work, most of the time the only planning you do is for what time you will be there.

TID:

When you arrived, what was going in your mind to create an opportunity like this?

JERRY:

I hate to overstate this, but I look at this photo as a real gift. What I came away with compared to my initial evaluation just makes me smile. After a few minutes of looking over potential shooting locations in the house, I felt a wave of failure pass over me. I knew I was going to be there a while, and it was not going to be easy. My immediate idea was to shoot a clean photo with smoke, a big pipe, and a dark background. I thought I could pull that off and not invest a huge block of time. I had already spent part of my day documenting a small grocery store that was closing up in a “food desert” area.

I needed to tone and create a gallery from that and my day was full before I walked in the door for this assignment. So after my first mental pass of how to handle this shoot I was pretty frustrated. Luckily for me, the house and how the tobacco pipe’s were displayed, did not allow me to take the easy path; but instead forced me into a new direction, made me react more on instinct. Looking at it now, a challenge like this is often the root of creating something special. It is strange how opportunity seems to live next door to failure. This is one of the things I love about photography and it is a constant theme to my portrait work. I kept the sense of failure up until the first few frames were made.

TID:

What problems, if any, did you have and how did you overcome them?

JERRY:

My standards for the portrait shoot were high since it was for the magazine. I did not want this portrait to look like some tired newspaper photographer shot it on the run. I figured the magazine’s regulars would be watching and critiquing, and I wanted to do something with the freedom that comes from working in the magazine arena.

The pressure was on. I paced the house back and forth multiple times, “give me just one bare wall, just one place to create a dark background,” I thought. There was none.

Tobacco pipes were on the mantel over a fireplace, and also hanging on the wall in two places in his studio. The crowded studio area seemed out since it was so full of boxes and papers stacked knee high all around the room on the floor. The lack of floor space and abundance of drawing tables prevented me from posing the subject close to any of the pipes on the wall. After about 30 minutes, I made the decision to go with the studio space. It was Jim in the middle of the room with pipes in a rack located 4 or 5 feet behind him. The biggest problem with the shot in the studio space was that I could not back up to get things composed using the 50mm lens. Eventually a few boxes were moved, and I ended up leaning against a wall with one foot on the floor and one atop a stack of boxes and papers that I was told was ok to sacrifice with me standing on them. Just clearing space must have taken 15 minutes. Luckily for me, Jim must have thought all the fuss was worth it. Watching this shoot would have looked pretty chaotic. This was definitely not an Annie Leibovitz shoot.

The basic approach I use for portraits is to try and create a photo that captures the spirit of the person, or a least reflects a strong facet of the person’s life. Portrait photography is a genre with such a very wide range to work within. The more controlled portrait shoots, like this one, really take a different skill set. Being able to keep a subject engaged as you dial in a shoot with all the rearranging of the location, posing, and lighting, is as important as your visual skills. I love working in this wide space where every situation is a new challenge. At times a portrait demands a hands-on and involved production with lighting, posing and incorporating items form the person’s life into the image, and at other times your portraits are very hands-off and documentary based. I feel is is important to make my posed and controlled portraits capture the person not mimic a documentary moment.

TID:

Now, onto the moment. Please walk us through how you photographed the moment and what was going on in your mind.

JERRY:

I have already established some of the obstacles. When I finally figured out how the subject and background were going to frame up, I needed to figure out how to light things. I used a pair of Canon 600EX-RT strobes along with the transmitter that gives me remote control of their power. One light is clamped to the molding running over the closet doors behind Jim’s head. It has a narrow angle grid on it and is aimed in front of his face where the smoke will be. The main light is sitting on a stack of boxes aimed to bounce off the wall and ceiling in the corner of the room. I spent some time shooting test shots and could see that the tobacco pipes on the wall are so far away that I am was going to need f8 or more to pull those into focus with the subject. I don’t really shoot that way. I hate seeing even a moderate depth of field. I did not want to see the closet molding behind Jim’s head. I used a trick I have evolved into my own private art form. I “free lensed” a 50mm 1.2 to alter the focus plane to slice through Jim’s eyes, his pipe bowl, and back to the left edge of the pipes on the wall. If you have ever used or seen a tilt-shift lens, it is the same general look except it is an even more shallow focus plane at f1.2 vs. a tilt-shift lens’ f2.8 minimum aperture. I can use this “free lens” technique with any of my prime lenses, but the 50mm is the easiest and most forgiving.

You dismount the lens from the camera and hold it to the body and allow the lens to have a slight angle change from its normal squared mount, all while using a finger or two to focus. The problem with this technique is that it so unpredictable and you absolutely look like you have no clue how to work a camera. You can’t always get the focus plane to do exactly what you want. You are moving a plane of focus through your shot that is a few millimeters wide (f1.2), and to do that you have to control the angle of the lens pushed up against the camera body mount to within fractions of a millimeter. The technique is aided by using a special focusing screen with a very heavy frosting. For the Canon 1Dx it is called the Precision Matte Ec-S. This focusing screen, or ground glass, allows you to manually focus a fast prime and really see the focus plane in a way the standard focusing screen does not. Most modern AF cameras have switched to screens the really do not give much focus feedback. I have heard the stock Nikon D4 is better than the stock Canon screens in this regard. Canon does have the best screen for this though with interchangeable Ec-S.

My A+ in View Camera class from college three decades ago, with its swing and tilt lessons, was about to pay off. The actual shoot was frame after frame of mediocre photos with one great one. The truth is, I probably could not reproduce it. There was just that one magical moment where the smoke had a nice form with a big section of out of focus smoke mingled with in-focus sections with a nice organic form. I happened to have the focus plane exactly where I needed it to slice through the core objects, and all it came together at once. After I saw what we had created, I was a little shocked. No, I never visualized what I wound up with before I started. I only wish I was that good.

Right away I could see that this image was really transformed in black and white. I toned out a color version, but could see the B&W was going to be the star. With the narrow plane of focus and the extreme swing of the lens the image was pretty soft with not a lot of edge detail. In post, I used a technique called dynamic sharpening. You use three or more passes of unsharp mask sharpening at different radius values, several passes with high radius values with low amounts, along with the normal sharpening for the fine detail. It is similar to the clarity tool in camera raw, but with more control. It, in effect, allows you to add contrast to localized areas. The smoke in particular was enhanced by this technique giving it more contrast. Lastly, since this was for the magazine, I added a slight warm tint to the shadows of the image for an Old World feel. The magazine editor was excited about the image, and it anchored the story.

TID:

You've had a long career in photojournalism, and it seems like you continue to improve and get better. In fact, just last year you were named the North Carolina Photographer of the Year, the North Carolina Sports Photographer of the Year (both by the North Carolina Press Photographers Association), the Southern Short Course in News Photography’s Photographer of the Year and the prestigious award of National Press Association’s Photojournalist of the Year (Small Market). What thoughts do you have on the effort it takes to continue imporving like you are?

JERRY:

Thanks for the kind words. It has been 28 years this summer. I have been fortunate to have kept the desire to always improve my art and craft and to have been able to evolve over that time. I have been blessed with endless support from my wife and daughter and my mentor, Rob Brown. They have all been instrumental in making my success happen. When Rob came to the paper 11 years ago as the Director of Photography, I was in real need of his abilities to mold, reshape and motivate me. It took him a few years to make me fully realize my potential. Once I started to focus on making every assignment better than my previous one, I was on a roll. He completely changed my way of thinking about myself and my work. I guess he gave me confidence in myself and freed me from thinking about photography wrapped in a box. Rob never let me think I had reached where I was going, but that I was on a journey with no real ending. It is really quite amazing to think of how much influence one person can have on another’s life.

At the same time that I was taking in Rob’s lessons and direction, I started to really look at the work of my fellow photojournalists in the state of North Carolina. Out state photo organization, the NCPPA (North Carolina Press Photographers Association), is a strong, close-knit core group of photographers. People like Andrew Craft, Ted Richardson and Shawn Rocco were a few of the people that seemed to resonate with me. I studied their work and all the shooters across the state and used it like a map to see where my work was lacking. I am sure they would scoff that they have influenced me, but it is true. In the past few years I have been influenced by photojournalist Scott Muthersbaugh. We have helped each other edit our daily work, our portfolios and generally propel ourselves at what sometimes felt like an exponential rate. As you may have figured by now, my philosophy to perfecting my photojournalism demands that I evolve, grow, learn and never think I have it figured out. I have to demand more of myself every hour of every day for the sake of the art. Because the truth is, no one else will do it for me. No one will do it for you.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

JERRY:

I have been mentoring a few folks lately, and I entertain myself with some of the crazy things that fly out of my head. Some advice I gave the other day was, “When on assignment, push past your fear of failure, don’t shoot the easy images, always gamble and be ready to wait, and then wait some more, for that one great photo instead of a gallery full of mediocre images. Never settle for what you have now, because your next photo should always be your best.”

EDITOR'S NOTE:

Recently there was a layoff at the newspaper of 9 people, 6 in the newsroom. His boss, Rob Brown, and fellow photographer, Scott Hoffman, were part of the layoff. Almost a month later, Jerry resigned.

:::BIO::::

Jerry Wolford’s camera and personality make a magical connection with the people and places he encounters. Though he has stood an arm’s length from history hundreds of times, he feels his strengths lie with documenting the lives of everyday people. After three decades in the daily newspaper industry, Jerry is bringing his exceptional skill set to the team at Perfecta Visuals. His vision and technical prowess are assets on any type of photo shoot, be it an annual report, a portrait, or an in-depth article for a magazine.

In 2015, Wolford was named the National Photojournalist of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association (smaller markets), was the North Carolina Press Photographers Association’s portfolio Photographer of the Year for the fourth time, and the North Carolina Press Photographers Association’s Hugh Morton Photographer of the Year (Daily Newspaper). His photographs are routinely published by magazines, newspapers and websites around the world. To follow Jerry’s work, be sure to check out www.perfectavisuals.com and like the Perfecta Visuals page on Facebook, as well as his website: http://jerrywolford.com/