Spotlight on Jacquelyn Martin

Feb 13, 2013

TID:

What a touching picture. Please tell us a little of the backstory of the image.

JACQUELYN:

Thank you. This project is very close to my heart and I’m honored to have it included in TID. This is such a wonderful resource for photographers and students, not just to learn from others, but to really think critically about our own process of doing documentary work.

This image is from a personal project looking at the dangers facing people who have albinism in Tanzania. I’m very interested in racial identity, and when I read that there is a fairly large population of people with albinism in Tanzania, I was fascinated. Initially I was interested in matters of identity. What is race when the central marker of color is stripped away? As I dug deeper I learned the horrifying reality that people with albinism in Tanzania have been hunted, maimed, and killed, as part of a black market. This black market is led by witch doctors exploiting traditional beliefs that albinos have magical powers, which can be accessed in potions made from their body parts.

As a result of these killings, the government has put adults and children with albinism into centers for their own protection. Often these centers are placed in existing boarding schools for people with disabilities, with little preparation to deal with the special educational and health challenges facing albinos. My interest began to turn to the nature of prejudice, and how society tackles such prejudice. Through interviews I learned that there is really no long-term plan for the people placed in these centers. Other people have done projects specifically on the killings. I wanted to look at the aftermath of those killings on the people currently living in fear and those ostracized from their communities.

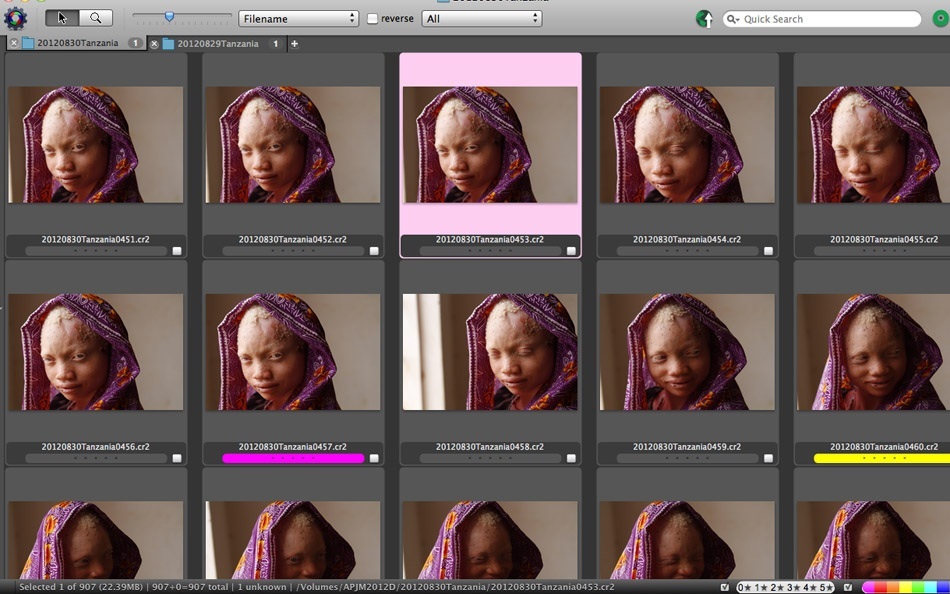

I decided to tackle the subject in two areas over a period of three and half weeks of my vacation time. Having been connected with a center via the northern Virginia based non-profit Asante Mariamu, I first wanted to document life in that center. Second, I wanted to photograph people with albinism who were still living in the greater community. It was while I was documenting life in the center that I started experimenting with portraiture. It was a complete surprise to me and interesting that the portrait series from the center has become one of the most emotionally connective parts of this work.

Over the course of a week I got to know the people living in the Kabanga Protectorate Center, and I particularly connected to a group of teenage girls. Angel, 17, is one of those girls. She has several cancerous lesions on her forehead, some of which have been removed. Angel needs treatment but the options for skin cancer treatment in east Africa are few, far between, and expensive. Through sheer luck, while I was there Angel’s mother visited for the first time in the four years that she had lived at the center. I interviewed them together during a portrait session and found out that Angel’s own father had led a group of men to attack her, during which her maternal grandparents were killed. It was an awful story but Angel seemed to tune it out as her mother spoke. On that day, I photographed Angel with her mother and half-brother (neither of whom have albinism) and then I photographed Angel again by herself the following day.

TID:

How did you prepare for this shoot or what did you to put yourself in place to make this happen?

JACQUELYN:

After several days at the center, I had gotten to know the people by hanging out, doing thorough interviews and opening myself up to questions. Even just talking with them about random things helped to build a rapport. This portrait of Angel was made the day after I had already done some portraits of her with her mother, so she understood the process. I found that many people living there had never had a formal portrait made. It seemed empowering for them to be listened to and paid attention to. Despite the language barrier, by approaching them photographically with dignity and respect, they opened up to me. And people just loved getting to preview the photos on the back of the camera. I really felt like it was a give and take, a collaboration. I think the tough interviews done after several days of being around helped to build that trust and make these intimate portraits possible.

It was important to me to make photographs that spoke to the beauty and unique personalities of each person. Albinos are reviled in Tanzania. To be different is to be scary, ugly, and even evil. I loved the spirit of the people I met at the center. Despite all they’d been through there was so much joy and sense of community for one another. I hope their humanity and beauty comes through in the pictures. I was very touched by their stories and the way they opened up to me. I really hoped to make humanizing portraits that they could be proud of. I’d love to use these photographs in the future to open up a dialogue about how society can tackle such a complex issue. Is hiding these people really the best recourse not just for them individually but for Tanzanian society as a whole? By showing the everyday reality as well as the beauty in a group of people that is vilified, I hope to expand this conversation and to humanize the issue, at home and abroad. My goal is to have a traveling exhibit, and I'm also interested in expanding the photographs with audio and video interviews to add their own voices to their image.

TID:

What challenges did you encounter while working to make this image?

JACQUELYN:

I wanted to be sensitive to Angel’s self-consciousness about her lesions while still showing them to the viewer, because skin cancer awareness is something that’s sorely needed in this population. Luckily Angel was very accommodating as I tried different poses, and she had this wonderful kanga, a traditional cloth, that could be used to frame the lesions without making them too obvious. I wanted her personality to come across, and I have many great frames that are more joyful than this one. However the serious gaze in this one suits the subject matter.

Another challenge for the portraits is that people with albinism have sensitivity to light, so even the window light could be painful on their eyes if I positioned them too directly. I made sure to ask, through my translator, to tell me if their eyes were hurting and I would modify accordingly. Another challenge that you can’t see in this image was the sheer chaos of the environment. The building I chose to do the photos in had wonderful open window light and a great white wall with a patina of dirt from the children's play. But it was also a site of great curiosity and to get more thoughtful moments I sometimes would ask my translator, Blandina, to chase away packs of curious children. (As most people at the center only speak Swahili, I arranged to have a translator with me.)

There were many challenges in the overall project. Logistics, distances, language, and cultural challenges all had to be forded in order to produce the work.

TID:

Can you elaborate on how you chose a translator?

JACQUELYN:

As I was researching, I looked for nonprofits working on the issue. I got lucky; Asante Mariamu is a small nonprofit and the founder lives in northern Virginia, quite close to where I live. I contacted her and arranged to have lunch. Susan, the founder, is amazing. She has two children of her own who both have albinism and was so moved by the plight of albinos in Tanzania that she started this nonprofit when she's not working as a lawyer. You couldn't meet with Susan and not feel moved. During our lunch I asked who they were working with on the ground in Tanzania and she gave me a list of names and emails to contact. One of those people was Rev. Bartholomew, who had recently returned to Tanzania to work for the Anglican Diocese. I contacted Rev. Bart, as well as several other people she had connected me with. Rev. Bart wrote back right away and offered to find me a place to stay, connect me with the center, offered a teacher from the Diocesan school who knew English to translate for me -- all free of charge. He was so passionate about the issue that he was willing to take me on sight unseen. It's really quite remarkable. The woman who translated turned out to be lovely -- an English teacher to secondary school students who was on break before beginning university, also very green with no experience working with journalists. So I had to do a lot of coaching, making sure she didn't speak over people or paraphrase, and I recorded interviews as a back up. I also had to explain to her how to ask questions so that people would rephrase and open up. It was quite the give and take.

At one point Blandina taught me how to wash my hair in buckets, and I then taught her how to use a hot shower for the first time. At the end of our time together I also bought her first pair of trousers as a university present. Her trying them on is one of my favorite memories of the trip.

I had picked up a couple simple words like, "That’s good" and "Left," "Right." I botched up Swahili and pantomimed and joked around to get Angel comfortable. There was something magical and connective in taking a group of people who have been reviled and made outcasts all their lives, and respectfully making a collaborative portrait about who they are, above and beyond their condition.

One father of several albino children, who I visited living in his village, told me that it gave him hope to have an American visit and ask for his story. That was so powerful and I am grateful for the chance to fill someone with hope if even just for an afternoon.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

JACQUELYN:

Since college I’ve been interested in the concept of documentary portraiture and the thought that through portraiture you can show something meaningful about a person’s character. I learned that I should trust my instincts. I’m glad that by looking over my takes every night, and seeing a glimmer in the first couple portraits, that I then committed to the concept and added some formal portraits into each day’s shooting. Most photographers realize something my mentor, Scott Applewhite, calls the “Time, Quality, Coefficient.” The concept that your images will increase in quality as you increase the time you put into the image-making process. I think this holds true not just for making the actual image but the effort and time you put into the groundwork. Doing your research means taking the time to talk to experts and look at previous work on the topic, making contacts, being clear with your helpers (or fixer) about who you are looking for so they can be identified before you arrive (saving you time on the ground), taking the time to really talk to and more importantly LISTEN to your subjects, being open to getting to know them and letting them get to know you.

Without all of this groundwork there is absolutely no way I could have accomplished all this work in three and a half weeks. Logistics alone (plane flights, cross country driving on dirt roads, introductions) ate up a good week and a half. If you look at both my reportage and my portraits from early on in that first week of work, they are just blown away by the quality of the pictures towards the end of the week. You really get back what you put in. I rarely have time to explore the “Time, Quality, Coefficient” in my daily work. More importantly, I rarely have time to connect with people. That connection is what initially attracted me to photography. In our fast-paced and digital-focused world there is a luxury in sitting back, being quiet, and letting the scenes play out as you capture those moments with your camera. Sometimes slowing down can be frustrating. Just waiting and watching can drive you a little nuts. I have to push myself past the typical half-an-hour that I’ve become accustomed to in my daily work. But it feeds my soul.

It’s amazingly connective and wonderful. The moments I get to experience: washing clothes as Epafroida laughs and tells me to put more “energy” into it, Blandina teaching me the finer tips of washing my hair in a bucket, getting hug after hug from little Yonge, Zawia slipping her hand into mine, earning Maajabu’s respect as I hang out all day while he pounds burned trees for charcoal, the gravity of sharing these stories with the world. It's an honor and great responsibility.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

JACQUELYN:

I think persistence is what makes this career possible. It’s a tough career and changing each year, but at the end of the day if you can make it five years you can make it for the long haul. There’s no shame in leaving the profession either. If you no longer absolutely love it, if the passion has been drained out, then it’s okay to move on. This is too tough, too competitive; too draining and demanding of a career to do if it’s not the only think you wake up in the morning wanting to do.

You never know when starting a personal project where it might lead. You don’t know if one person will see it besides you. And you know what? The world doesn’t owe you some big venue for your work. YOU have to make that happen. Show it to friends, show it to editors, show it to strangers, ask for feedback, get your work out there. Apply for grants, look at venues outside traditional photojournalism publishing. And don’t take no for an answer if it’s work you feel strongly about. I am lucky that as a staff photographer for the AP I have an outlet. But I am still the one out on the street showing the work to people. You know what? Many outlets were not interested in this work. But NPR’s Picture Show was, and National Geographic online picked it up from a showcase on the AP site. After months of re-editing I was able to get an article I wrote on the topic to go live on the AP wire. Point is: this is a subjective business. Believe in the importance of your work. Don’t let the people who let you into their lives down. Don’t let the work die a slow death on an external hard drive. Do all that you can to give life to your work. Projects that you are passionate about, have put your full self into, those projects tend to take on a life of their own. Don’t give up.

:::BIO:::

Jacquelyn Martin (b. 1979) carves out time from her work as a staff photojournalist with the Associated Press to work on personal projects. Race, identity, immigration and women’s issues are common themes in her work. Born in Syracuse, NY, she graduated with honors in 2001 from the Rochester Institute of Technology. For the AP in Washington, D.C. she covers a diverse range of topics from the President and Congress to the National Spelling Bee. Prior to working with the AP she was a staff photographer at the Birmingham (Ala.) Post-Herald, and worked as a freelancer for clients including The New York Times.

Her work has been honored with awards from the White House News Photographer’s Association, National Press Photographers Association, and the Women Photojournalists of Washington (WPOW). She is the current President of WPOW, a non-profit that educates the public about the work of female photojournalists.

As well as the AP article: http://bigstory.ap.org/article/ap-photostanzania-albinos-hope-more-govt-help

She is also on Twitter @jacquelyn_m and Instagram http://instagram.com/jacquelynmartin#

To learn more about how you can help people with albinism in Tanzania contact: Asante Mariamu (http://www.asante-mariamu.org/)