Spotlight on Eman Mohammed

Jul 28, 2018

EDITOR'S NOTE:

This guest interview was done by Katie Wood (thanks Katie!). If you, or someone you know, is interested in doing an interview, please contact

Ross Taylor @ [email protected]

TID:

Hi Eman, your portrait series touches on a tough issue. Can you tell us about the idea behind this series?

EMAN:

I've covered wars and conflict for so many years. All through the catastrophic events I have documented, I've realized that my job as a photojournalist is to deliver an impactful message, the truth and the facts, but in a way for the public to learn and educate themselves about what is happening in the world. But, instead I saw there was a major gap between the directly effected nations and the international audience.

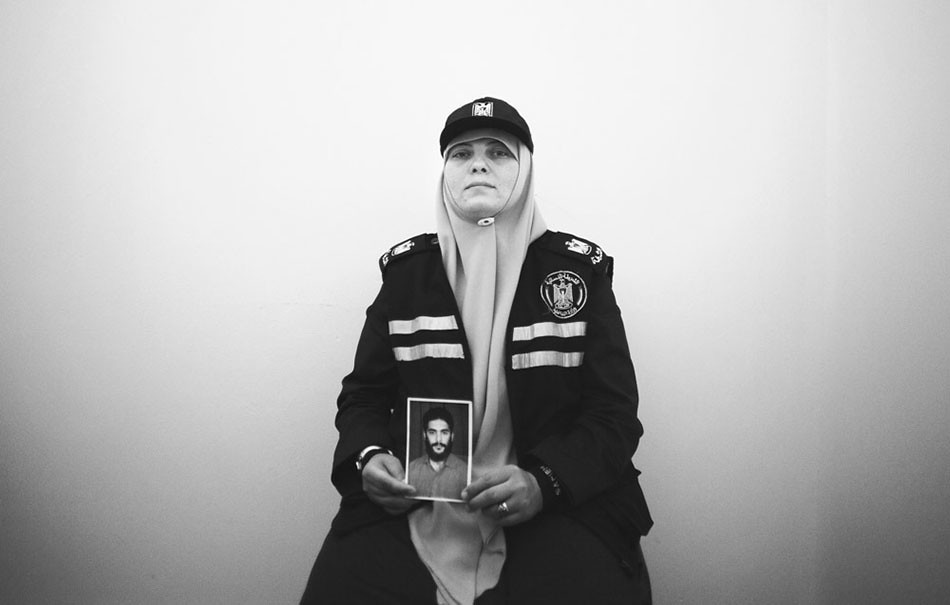

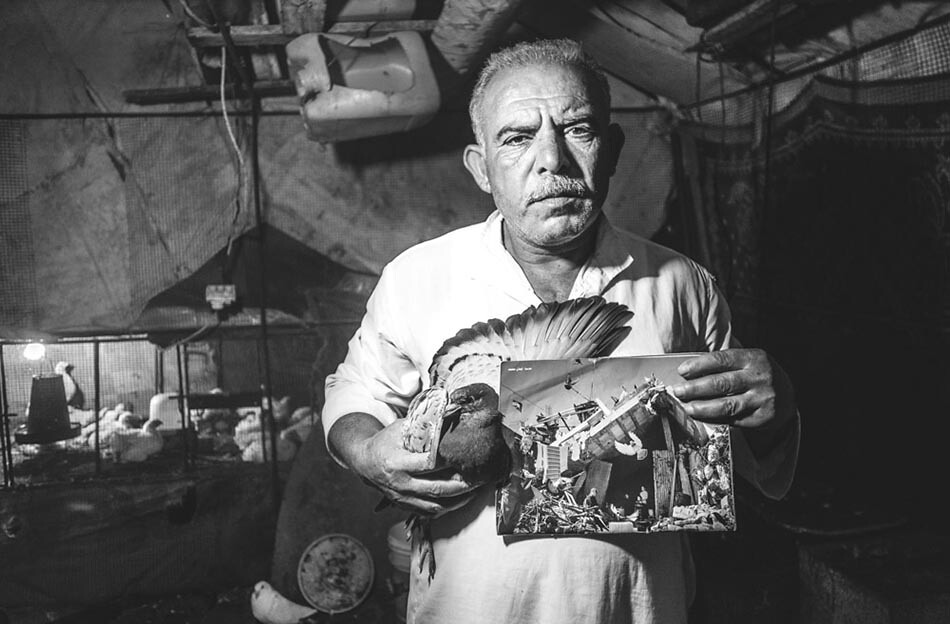

People started to shut down to the overloaded bloody images and news that relied mainly on counting the casualties and death toll. This photo series was my idea to possibly let people see how they can relate to these "war zones.” Instead of alienating the people who experienced the tragic deadly conflict, they can see portraits of individuals from different times in history and very remote areas in the world, all connected by the six degrees of separation, which means each survivor/victim knew the other through six people or less.

The main concept is that pain knows no nation and at times like our current time, it becomes a universal connection.

TID:

In the past, you have covered Palestinian daily life and the immediate aftermath of conflict. Can you talk about how the idea of doing a portrait series came about?

EMAN:

I think the main motivation was frustration, as the conflict continued and no actual change was occurring, to prevent more similar events from happening. So, the idea of the portraits was meant to show a graphic image of the war but without reflecting any blood or body parts.

The mental trauma is very clear through the subjects’ words and captions, and through the objects they choose to fill the void of their loved ones and losses with. The idea is that war photography can be graphic but doesn't have to always address us in the same way. There are so many angles that get neglected on a daily basis.

TID:

How did you find your subjects? Was it difficult to get any of them to agree to participate in the series?

EMAN:

For most of the people who decided to allow me to tell their stories and interview them, it was crucial that they go back in time and re-live these moments. But, it was harder to even address the present and how they feel now, so overall it was very tricky to get many of them to open up and participate.

Some even revoked permission moments before I start interviewing them, others had cold feet after months of coordinating and traveling back and forth. I walked into the project knowing that it wasn't going to be as easy as just a quick interview, especially considering that I was going to discuss tragic events from their past.

TID:

You've often photographed people who have been through a lot of trauma and loss. Can you talk about how you approach people about such sensitive issues?

EMAN:

I walk all the needed miles in their shoes, I put myself in their place and since I've lived and worked in a war zone for a very long time, I can comprehend how difficult it is for others to address their trauma as it is for me.

I give the people I photograph enough space to not feel pressured. I guess mainly the key is listening rather than treating the stories as "names and numbers.” They are real people with real lives that I have so much respect for, and I make sure they know that.

TID:

Did shooting this portrait series change anything about how you work as a photographer?

EMAN:

It underlined once more the importance of not drifting away from the stories because they are "quiet.” It made me focus more on the deeper layers underneath the explosive headlines in the media. I no longer run when I hear an airstrike, but rather look around and observe more carefully what happens after the events are labeled as "over.”

Starting this project, I was desperate for closure as I struggled to understand the "open ending" we mainly experience while covering wars, and I realized it was here all along. The legacy of one survivor can eliminate a lifetime of war, that is how much resilience these stories hold.

TID:

The Broken Souvenirs portrait series was a project you generated on your own, right? Did that affect how you worked on the series at all?

EMAN:

Yes, it is. I think it allowed me to have more time examining the stories and talking to the storytellers (subjects). I've not felt the pressure of being on a deadline and that helped me sink deep into the stories and respect people's privacy since I didn't need to answer to an editor myself.

But, it also had its own heavy weight as I had to coordinate everything from A-Z and cover all the funding as well. I edited over the course of months and years and a lot of obstacles presented themselves to me to deal with on my own, which as you can imagine, slows down the workflow.

TID:

You are currently living in D.C. How often are you still photographing stories in Gaza and the Middle East?

EMAN:

I manage to move back and forth and travel occasionally. I'm no longer focused on the Middle East on a daily basis. I work on longer term projects that allow me to have gaps between my visits, and I am exploring other communities and stories within where I am, or where I travel.

TID:

You've spoken publicly about working as a female photographer in Palestine and having to overcome discrimination for that. Now that you are further along in your career, do you continue to face these challenges?

EMAN:

Not a single thing changed in that situation. I'm more vocal, and feel like I'm much more confident, not only to defend my career and my work, but to also lend support to other women colleagues whenever is needed. I don't think any male-dominated field suddenly changes and accepts women in the field.

It is a very lengthy process that I can’t focus on for the time being. I've worked for a decade while the community treated me like I don't exist, and therefore, now I'm working as though these unfair discriminatory taboos don't exist, or shut it down.

TID:

Can you talk about the main image and how you came up with the concept?

EMAN:

I wanted to have a "normal" portrait, a family portrait if you wish, that shows normal families with their loved ones, with the loss of their loved ones. I asked them to choose "souvenirs" to fill the void left by the absence of the victims.

For an example, in the photo of Ziad Deeb, he lost 12 of his family members and choose to have their photos printed out and placed on their chairs in the house as he remembered them when he saw them last.

TID:

Can you talk about the current state of female photographers in the Middle East? Do you think your own work and success has helped other female photographers?

EMAN:

I don't think it helped them enough. In theory it might have inspired ambitious talents to keep going, but it didn't do enough to protect them or help them move forward. I wish it did, but the reality is that women in the Middle East face triple the obstacles that women photographers and journalists face elsewhere. The only way to overcome that is by providing education, resources and on the ground support, not just examples of people who might have "made it.”

Female photographers are doing amazing work under a LOT of pressure from the community, from the field as well, and I believe it is a transitional time that is very tricky to navigate while considering the explosive political situation after the Arab Spring. It is complicated to say the least.

TID:

Do you consider yourself a conflict photographer? Do you plan to continue covering conflict in the future?

EMAN:

Yes, I'm proud to be a conflict photographer, although I had a very complex love-hate relationship with the title. I do plan on covering more conflict, but not in the traditional meaning and understanding of war photography. In my opinion I accomplished nothing if the gap between the war world and the rest of the world isn't bridged.

As human beings we tend to make the same mistakes and we never learn from history, but that is where the important role of photojournalism comes in as a visual testimony. How that is presented to the media audience globally can be a game changer.

Therefore, war photojournalism needs to cover a wide range of stories and not stereotype like we have for decades.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers who cover conflict?

EMAN:

If I would address photographers in conflict zones I would say being professional doesn't mean you are a robot. Be a human in every interaction with your stories. Most of our rules (except the ethical ones) are a myth. Get involved, get closer and don't apply a mold to your stories. Going into a story with a previous agenda is an unforgivable sin in journalism. That said, the desperate look for neutralism isn't realistic either.

You are not a storyteller, you are a messenger. Get the exact facts as they present themselves and deliver that to the audience without any changes. In the end the media's role is to educate, but it is up to the public to seek the information and act upon it.

That is the long lesson I learned from all my colleagues who lost their lives dedicating themselves to documenting the truth.

+++BIO+++

Eman Mohammed is an award-winning photojournalist and TED fellow, currently based in Washington DC. Eman is a Palestinian refugee, born in Saudi Arabia and educated in Gaza City, Palestine, where she started her photojournalism career at the age of 19.

Her work has been focused on documenting the Israeli/Palestinian conflict for the past decade, including military invasions and wars that frequently occur in the area as well as the formation of armed militant groups in the strip. The main body of Eman’s work has moved from covering the Israel's bombing blitz in a hard-news style to a series of long-term and in-depth aftermath projects and women-unraveled stories in culturally sensitive communities.

Her work was published in The Guardian, Le Monde, VICE, Washington Post, Geo International, Mother Jones, and Haartez. It has also been recognized by several international organization and was recently acquired by the British Museum in London, shortly before Eman was announced to be one of the TED Fellows.

You can see her work here:

Katie Wood is a video producer for SFGate in San Francisco. She got her start in the photojournalism world editing photo galleries at The Denver Post but eventually transitioned into all things video. She is a firm believer in the power and importance that photography and video bring to journalism. You can see her website here: