Spotlight on Chris Arnade

Jan 9, 2013

TID:

This is a powerful and disturbing image. Please tell us a little of the backstory.

CHRIS:

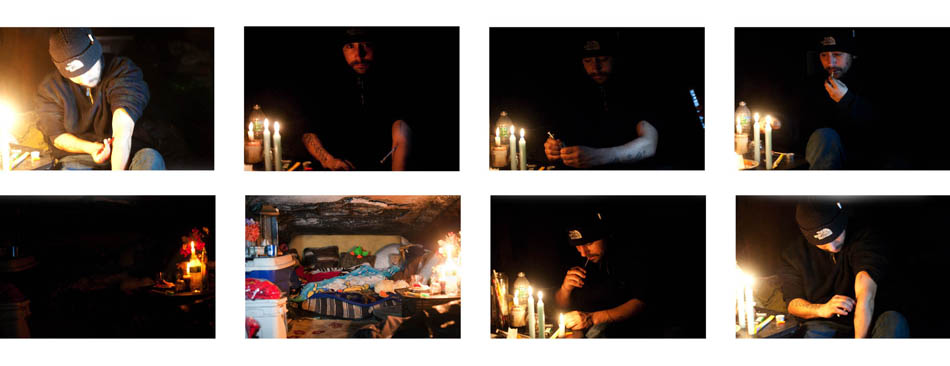

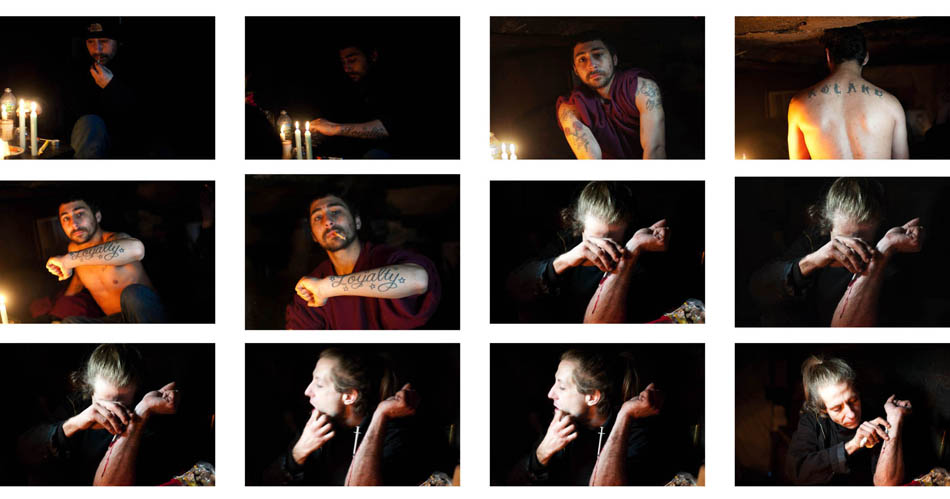

The subject, Michael, is a transsexual addict who prostitutes for money. He has become one of the primary characters in my series on addiction in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx. He is now my friend. This picture was taken in the small space he lives in with other addicts. It is hidden in amongst a tangle of roads and trains, only accessible by crawling for about ten yards along a water pipe and climbing through two tiny holes. They call it The Cave.

It was about my tenth time inside. This time I had brought a small LED light box to try and capture a few pictures of the beds. While I was shooting, Roland, another addict, came in with a few bags of heroin. I decided to catch a few pictures of them shooting up. I tried to maneuver into a position where I could get somebody in the frame. I ended up lying on my back, light propped against my stomach, head hitting the ceiling, hoping that the sharpness against my back was something benign. I had to shoot at f/2.6 and 1/6th of a second, so much of the arm is out of focus.

Michael, when done, looked up at me, smiled and said, “See what you did. You made me get blood on your boot!”

TID:

This is part of a larger body of work, called "Faces of Addiction." Can you tell us more about your larger project?

CHRIS:

It’s a series I started about three years ago. I have always relaxed by taking long walks with my camera. I was drawn to Hunts Point partly because someone told me not to go there, that it was New York’s most dangerous neighborhood. The project started slowly, with me using my camera to get to know a neighborhood I was fascinated with. I would spend my weekends and nights just talking to anyone and everyone, bodega owners, pimps, drug dealers, gang members, prostitutes, addicts, etc. What I found was so different than what is portrayed in the media.

I decided to start taking portraits of the addicts: photos with the face lit, looking directly into the camera. Conventional photos of unconventional people. I wanted to post their story, as told to me, beneath the photo. I wanted to force the viewers to get to know the subject. I did not want to fall into the easy “gotcha” style that uses long lenses and shows addicts without knowing them. It was important for me to get to a point where I knew my subjects to the degree that I could take a true portrait.

TID:

I read that you're a banker in New York, that you're not a professional photographer by trade. Is that correct? If so, what is your motivation to do this kind of work?

CHRIS:

Yes, I was a banker for twenty years, but quit a few months ago, partly to work more on this series (stupid financial decision!) Photography has always been a way for me to relax, to view the world from a different perspective. Banking is very top-down: working with statistics, seeing the world in a very macro way. Portraits provide me a chance to look at the individual, to understand the importance of every voice.

TID:

Will you tell us more about your decision to leave your job and pursue photography? It's tough to make make photography work financially.

CHRIS:

Not to sound cliched, but you only live once. I will give it a few years, live off my savings, and if/when it does not work then I will find another job, probably back on Wall Street (which I love doing) or working for a non profit. Its sad to me that one of my advantages for doing this project is that I don't care about money. Sad that nobody really cares enough for this type of work to pay.

I have loved the last six months, despite the financial stress. I look at how my subjects live, with nothing, and yet they don't give up. They still have plenty moments of joy, laughter, and happiness. Do I really need to live in a huge house in a rich neighborhood in Brooklyn?

TID:

What challenges do you encounter while working on this project? What challenges have you encountered while making this

specific image?

CHRIS:

This image was physically one of the hardest. I hate The Cave. I am 6-2, 210 lbs. I barely fit inside, and I usually get a cut or scrape making it in. I have little time or light to work with. Their are always people coming and going, some who I don’t know yet. There is always something distracting my focus. The overall project has been about getting respect and access. The neighborhood is 99% black and Hispanic; I am neither. When I began, many in the area thought I was a cop or a john.

TID:

How did you handle and overcome these problems?

CHRIS:

I had to build trust. That has come from putting in the hours, never saying no, and showing and having no fear. If an addict wanted me to come with them to an abandoned house at 3 am, I would go. Or making small gestures, like handing my camera to someone when I first meet them to let them take a picture of me. Its my way of saying, “Here, take my camera, I trust you.”

I also made sure to always come back with a print for my subject. That is not only the moral thing to do, but it also is a huge help in building relationships.

For individual photos, the biggest lesson I have learned is to try and anticipate the shot. I often have at most thirty seconds, if that. Nobody has the patience for me to fiddle with the f-stop.

TID:

Now onto the moment. Can you talk about the moments leading up to the picture and also the actual moment?

CHRIS:

I was frustrated. I was wet and my camera and glasses were fogging up. The Cave had three others inside beside me. I was trying to maneuver towards the back but kept hitting my head. I have photographed many addicts shooting up, so I knew the shot I wanted. I just did not know where Michael was going to inject himself. Just as he started to work the heroin into the needle, another addict came into the space. She did not know me, and started to yell. Michael tried to calm her down, all while working to get his fix.

I had ten shots left on my card, so I was trying to be patient, trying to hold the camera as still as possible while not jarring the light resting on my stomach. I had no clue initially if the shot worked, if I had held the camera still, if I had managed to get the focus on his face.

TID:

What surprised you about the moment?

CHRIS:

The Blood. Michael was messy. He is usually quick, but the needle jammed. I had more time to get the shots, but I was worried about him.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself in the process of making images like this?

CHRIS:

I have learned more in the last three years working on this project than I learned in twenty years on Wall Street. I have learned humility, I have learned how resilient humans can be, how, as brutal and bleak as life gets, people can find humor and friendship. I have learned how unfair our society is, how no matter what anyone says, hard work alone cannot pull you to the top. I have learned how many children get sexually abused, how it never leaves them, how it often ends in a lifetime of abuse at the hands of johns, pimps, and society as a whole.

I knew all this before, but never really understood it on a personal level. It’s made me very frustrated with our culture, and in many ways, with the person I used to be.

TID:

You said, "I have learned more in the last three years working on this project than I learned in twenty years on Wall Street." What have you learned on the streets versus Wall Street?

CHRIS:

I loved working on Wall Street - it was intellectually challenging. But it was not necessarily fulfilling. What I've learned in the last three years is: the notion that everyone is given an equal chance, that success is about hard work - no matter your beginning - is simply untrue.

I am now friends with people who some others would think friendship would be impossible: prostitutes, addicts, pimps, dealers, and gang members. They do some awful things, often by necessity. They have complex problems, dreams, hopes, and all the other qualities that pretty much every human has.

Katherine Boo has a wonderful quote that is perfectly apt. "There's some way in which we would prefer not to see very clearly the immense gifts and intelligence of some of the people who live in our most abject conditions. Maybe there are some things at work in deciding who gets to be society's winners and who gets to be society's losers that don't have to do with merit."

TID:

What have you learned about others?

CHRIS:

How many people want to tell their story. If you engage them on a respectful level almost everyone will open up.

TID:

While doing some research on you, we saw an NY Times article about your work, and we saw that you on some occasion pay the people you photograph. Do you mind offering your thoughts on this? I think it's worth discussing, especially in an era that often blurs between photojournalism and photography.

CHRIS:

I have no issues with paying my subjects. With the prostitutes, it's a matter of their time. The addicts - I only give them money if they are in an awful jam. If you have ever seen someone dope sick it's hard to watch without trying to do something. Even if that means throwing them a dime bag to get through the day.

Here is an article I wrote about the complexity of the issue:

TID:

In the comments section of the article you added in response to someone:

"What I am hoping to do, by allowing my subjects to share their dreams and burdens with the viewer and by photographing them with respect, is to show that everyone, regardless of their station in life, is as valid as anyone else."

Why do you think you're motivated to do this?

CHRIS:

Glad you found that quote. Hmmm. My father had a very similar world view. I grew up in a small southern town of 400 people, and my father and mother spent all their time fighting for civil rights during the '60s and '70s. My family had death threats. I was attacked in school for being a "nigger lover." I grew up seeing and living both sides of a very decisive issue. It taught me to respect everyone. And to be careful when making judgements.

About six months ago my mother looked at my photos and commented, "Your dad would of been very proud of you, I guess we taught you more than we realized."

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for photographers?

CHRIS:

Take risks. Being scared of someone is presumptuous and often insulting. Find a project that drives you and just jump in with all you have. If you are doing portraits, take the time and be open enough to become close to your subjects. Many people want to tell their story. If you engage them on a respectful level almost everyone will open up.

:::BIO:::

Chris Arnade started playing with cameras as a child, building pinholes out of Lego. While getting a PhD in Physics at Johns Hopkins he built a few more, this time with lenses.

While working on Wall Street as a bond trader, from '93 till '12, he spent much of his free time walking around New York with his camera. Five years ago he noticed flocks of pigeons circling over run down buildings. It became his first photo series, Pigeon Keepers of NYC. (http://www.flickr.com/photos/arnade/sets/72157625271382891/).

The pigeons took him to the Bronx where he fell in love with Hunts Point, New Yorks poorest neighborhood. He started spending all his free time in Hunts Point, focusing on the addiction and drugs in the area. He left his Wall Street job six months ago to focus on the series Faces of Addiction.

You can see more of his work here:

Twitter